|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| SQMP ToC Wang Shixiang article Nie Zheng Later short melody More images Henan | 聽錄音、看五線譜 my recording and transcription / 首頁 |

|

02. Guangling Melody

1

- Manshang tuning:2 1 1 4 5 6 1 2 |

廣凌散

Guangling San Xi Kang about to die 3 (full image) |

The guqin melody Guangling San (san-type melody4 from Guangling5), as preserved in

tablature form in the handbook Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425 CE), is one of the grandest of ancient melodies. Based on this earliest surviving version, interpretations of which average about 20 minutes in length, it is a very complex, virtuosic piece that almost certainly survives largely in its current form since at least the 12th century, with much of it also quite likely dating from centuries earlier. For centuries the surviving melody has commonly been attributed to the famous essayist and poet Xi Kang (223 - 262). However, some have even argued that its origin may actually go back to the Han dynasty or earlier.6

The guqin melody Guangling San (san-type melody4 from Guangling5), as preserved in

tablature form in the handbook Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425 CE), is one of the grandest of ancient melodies. Based on this earliest surviving version, interpretations of which average about 20 minutes in length, it is a very complex, virtuosic piece that almost certainly survives largely in its current form since at least the 12th century, with much of it also quite likely dating from centuries earlier. For centuries the surviving melody has commonly been attributed to the famous essayist and poet Xi Kang (223 - 262). However, some have even argued that its origin may actually go back to the Han dynasty or earlier.6

As for the theme, or stories, connected to the surviving versions of this piece, this is somewhat in dispute. The accompanying article by Wang Shixiang, translated here, suggests the dispute is between two stories connected to the surviving versions, in particular through the titles of the various sections of the melody. These both concern a swordsman named Nie Zheng who is said to have learned the qin in order to gain the opportunity to get revenge, as will be further discussed in some detail below (see also these comments connecting qin and sword). However, credit for the melody itself is almost universally ascribed to Xi Kang. And whereas ancient records do connect Xi Kang with a melody of this title, and they also mention a melody connected to Nie Zheng, there does not seem to be any hard evidence connecting Xi Kang himself to any stories or melodies about Nie Zheng. This suggests that whatever the melody was that Xi Kang played, it was/is unconnected to any of the surviving versions of Guangling San. More specifically, either his melody was preserved but after his death the new titles connected to Nie Zheng were added; or a new melody was created on the theme of Nie Zheng but for some unknown reason the melody was ascribed to Xi Kang.

Perhaps a compromise on these possibile origins lies in the story that Xi Kang taught his melody to no one but, instead of it dying with him, someone who had heard him play it was able to reconstruct the original. However, for reasons that are not clear, this "re-creation" of the melody then had the story of Nie Zheng attached to it. Of course, this particular story is complicated by the fact that there was already in existence at the time of Xi Kang one or more melodies on the Nie Zheng theme.

To sum this up, much about the origins of the actual surviving melody remains very speculative. This is true about both its possible connection to Xi Kang and his philosophical outlook, and about its possible origins as a melody that concerns Nie Zheng. This, then, gives the person who plays the melody the option of thinking of the melody as telling a violent story of revenge, or to ignore the melody's subtitles and treat it as a more nuanced expression that perhaps connects to the philosophy of Xi Kang.7

The Nie Zheng stories

The Nie Zheng stories do not seem directly to have been connected with versions of Guangling San until the early Song dynasty

(except perhaps by deduction; for this see Wang, Table 1). However, the present page is largely concerned with the version as preserved from 1425, which does overtly concern the Nie Zheng story. As such, this part of the commentary is in line with the history of this melody subsequent to 1425. As can be seen from the chart below, the title Guangling San appears in perhaps 10 later handbooks to 1910. However, other than the two other full versions that survive from a handbook preserved from 1525 CE (discussed in some detail in the accompanying article by Wang Shixiang), the later editions of Guangling San were either copies of 1425 or were largely unrelated shorter melodies.

Likewise, although the stories connected to existing versions of the melody have consistently been a sympathetic account of the commoner Nie Zheng killing an unjust official for revenge, there were actually two basic versions of this story, with no apparent early consensus about which version was the actual source. The two are:

As for the music itself, the accompanying "Explanation of the Guqin Piece Guangling San" by Wang Shixiang, in addition to including a lengthy discussion about the two stories connected to the piece, also has extensive details from the Tang and early Song dynasties about the preservation and development of the melody.

As suggested above, there are actually two early titles connected to this melody:

Nie Zheng was a retainer skilled in music who lived in the fourth century BCE, and so melodies associated with his story could have dated at least from the Han dynasty, if not earlier. In addition, it has been suggested that such melodies were the same as, or at least associated with, a melody that originally is mentioned using the shortened name Guangling. This melody was a part of many ancient repertoires including ensemble and solo sheng mouth organ, pipa lute and hujia reed pipe.11 Just how many different melodies these stories and titles may have represented, however, is impossible to say. Likewise, if any parts of these melodies survived into one of the later Guangling San melodies it is impossible to say what parts these might be. This uncertainty is accentuated by the variety found in the earliest surviving versions, from 1425 and 1525.12

The aforementioned 2nd century CE introduction to Nie Zheng Stabs the Han King relates a story given with several Nie Zheng biographies. Here is a summary (the Qin Shi version is shorter):

Although there is no mention here of Guangling, and the preface by Zhu Quan in Shen Qi Mi Pu (SQMP; 1425) discusses only the transmission of Guangling San, without saying anything about its theme, the subtitles in the version of Guangling San Zhu included in his handbook show that his version of Guangling San in fact tells the story related in the Qin Cao. This suggests that Guangling, an ancient name usually referring to a place near Yangzhou in Jiangsu but here quite possibly to one in Henan, may have been the place where at least one form of the actual melody originated.

Xi Kang and Guangling San

As for Xi Kang's own association with this melody, although he might have played or even created a melody with this title, arguments supporting his connection to the modern melody seem to be based mostly on logic as there does not seem to be much textual evidence to support a contention that what he played or created had any connection to the surviving melody or to the story connected to it.

Xi Kang lived in the Wei dynasty capital of Luoyang, where he was a leading literary figure and one of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. In his poem Qin Fu he mentions "Guangling" together with the titles of several other old melodies. Thus if he actually had a role in the creation of a qinmelody called "Guangling San" it would seem to have been by modifying an existing song or instrumental melody.

One tradition says Xi Kang learned Guangling San from a qin master named Du Kui13 and/or his son. Nevertheless, the account here in SQMP follows a popular tradition by saying that he learned it from a ghost while stopping at Huayang Pavilion14 on his way from Luoyang to (his ancestral home in) Kuaiji.15 Perhaps one can speculate that if something significant did happen at Huayang Pavilion it was an experience which led to a revised version.

Xi Kang was patronized by the Wei imperial family at a time when real power was being gathered into the hands of the Sima clan, who in 265 were to take over direct rule as the Jin dynasty (later called Eastern Jin; Western Jin ended 420). Meanwhile Xi Kang had been executed for offending an official who had the backing of the powerful Sima elite. According to tradition, Xi Kang played the melody one last time at the exhibition ground (see illustration above).

Textual and melodic connections between the versions of Guangling San published in 1425/1525 and the one(s) played at the time of Xi Kang have been the subject of some research and considerable speculation. The argument that Xi Kang's Guangling San had a theme unconnected with a Nie Zheng story has been mentioned above. The argument that the surviving melody has a musical connection to a Guangling San at the time of Xi Kang suggests there is evidence for this from at least as far back as the Tang dynasty, if not to Xi Kang himself.16 This argument centers on such factors as Zhu Quan's own specific commentary on its transmission; the tablature's inclusion in SQMP Folio I, said to consist of the most ancient pieces; the number and titles of the individual sections; the old fashioned nature of much of the actual tablature; and numerous literary references, in particular poems by

Yelü Chucai and others.17 At a minimum these arguments show that it is very likely that the SQMP tablature was in existence at the end of Southern Song dynasty. It is also from this time (again see

Wang, Table 1) that we see sub-section titles that specifically connect the melody Guangling San to stories of Nie Zheng.

They also make a good case that what this tablature prescribes quite likely was then already very old. However, in the absence of any earlier tablature it is very difficult to assess what musical changes might actually have taken place over the preceding centuries.

Structure and transmission of Guangling San

The Guangling San published in 1425 is the longest piece in the living qin repertoire (44 sections grouped into six divisions).18 Its transmission since 1425 (see below) is more certain than what was just described for pre-1425, but it is still complex. Although qin tablature for Guangling San survives in at least 11 handbooks from 1425 to 1911, there is little variety in the full versions (other than the fact that there were two of them, as had been discussed by Zhu Quan); instead there are various shorter versions that are clearly later creations or revisions. Today Guangling San is very popular but usually in versions abbreviated from the 1425 tablature, which was reconstructed in the 1950s (more on this below). The full versions require at least 20 minutes to play, but rarely does one hear a version lasting even one third of that.

Guangling San might also be considered one of the most controversial qin melodies, some players saying the theme, particularly its violence, is inappropriate to the qin and thus should not be transmitted. Comments by Wang Shixiang, in his long and detailed Explanation of 0the Guqin Piece Guangling San, show that the controversy about the theme (whether it concerns Nie Zheng killing a king, Nie Zheng killing a minister, or is even a piece commemorating a battle at Guangling) goes right back to the earliest years of the piece.

Other factors beyond this controversey also suggest that the full version of Guangling San may rarely have been played throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties (the article by Wang Shixiang provides somewhat more evidence for it having been played during the Song dynasty). The second surviving tablature, in Fengxuan Xuanpin (1539 CE), is simply a copy of the SQMP version, not adding punctuation as it usually does. Zhu Quan wrote that there were two versions from which he could choose, and Xilutang Qintong (1525 CE) has two versions, one related to the SQMP version, though with many differences, and one very different from that in SQMP.

After the two versions in 1525 the only publications of full-length versions of Guangling San are the versions in four later handbooks (lined up to the left on this tracing chart). Dated

1539, 1670, ≥1802 and 1910, these were virtually unchanged copies of the 1425/1539 version. While this may suggest a certain reverence for the melody, it also suggests the melody was not actively played: melodies in the active repertoire tend to show change over time as players make the melody their own. Thus the history of a full Guangling San piece after 1425 seems to suggest that it was highly regarded but rarely played.

| Later short versions: a new melody 19 | 1634 Guangling San w/prelude (complete pdf) |

(More extensive commentary on versions of this shorter Guangling San [including the footnotes] has now been moved

here.)

(More extensive commentary on versions of this shorter Guangling San [including the footnotes] has now been moved

here.)

Basically, although after 1525 the only long versions of Guangling San that were published were the four dated 1539, 1670, ≥1802 and 1910, copied directly or indirectly from Shen Qi Mi Pu, variations on a newer Guangling San first in 9 then later 10 sections appeared starting with the prelude and melody in the 1634 handbook Guyin Zhengzong (IX/382). Though also called Guangling San, using the same lowered second string tuning, and perhaps sharing some musical motifs, these were in fact variations on a completely new melody

The first of these new versions (and the model for all the later ones) begins with a unique prelude, called Guangling Zhen Qu ("Guangling's True Essence", also referred to as a "Kai Zhi"; compare) followed by a Guangling San in nine sections. The Guangling Zhen Qu prelude appears only here. The handbook itself does not seem to have any related commentary.

Today it can be said that Guangling San is part of the active qin tradition, but that it did not pass into the contemporary repertoire through direct transmission. Until the 1950s its most recent publications in full form were those dated back to ≥1802 (in a handbook that simply copied it from 1425) and

1910 (in a handbook that copied out the tablature from 1539 within a format that used a new system to try to indicate notes and rhythms [see pp. 1 &2]). This suggested that there was a consistent interest in the melody over time, but that it was not actively being played. If it had been, someone would have made it "their own" and new tablature would have ensued (see

this comment on other tablature from Shen Qi Mi Pu Folio 1). This is also a main reason for the tablature for guqin melodies generally changing over time. Indeed, if new tablatures were made for the

various Guangling San recordings made during the 1950s each would show clear changes.

As for how these reconstruction came about, it has been said that a well-known qin collector, Xia Lianju,22 offered to give the reknowned qin master Guan Pinghu a famous Tang dynasty qin if he would reconstruct the piece, a promise carried out after Guan recorded his interpretation in

1954.23 A transcription of this that had been edited by the 中央音樂學院 Central Music Academy was then published by 音樂出版社 the Music Publishing Society in Beijing in 1958. The other 1950s recordings were clearly made through mutual consultation.

However, there were also serious political dimensions to the reconstruction of this melody. When Guangling San was revived in the 1950s, it was a time when the qin's close association with the literati should have made its position quite tenuous. Nevertheless, perhaps due to the political connections of Zha Fuxi, much valuable research was done. As part of this, great efforts were made to make the instrument politically acceptable, and for this Guangling San was most appropriate. Much was made of the fact that in this piece the first two strings are tuned to the same note: the first string was said to represent the ruler and the second string the vassal, so tuning the two strings to the same note symbolized their equality.

Past comments on the significance of these two strings being tuned to the same note were not so positive. These go back at least as far as the Tang dynasty's Han Gao, who was very critical of this as apparently was the neo-Confucian philopher Zhu Xi (1130-1200; see quote from Ziyang Qinshu). The in the 14th century there was also criticism from 宋濂 Song Lian (1310-1381), who mentions the strings as well as violence.

Here one might also suspect that one of the reasons for it not being played more was its length and complexity. Is it more likely that a player wiill give this as a reason for not playing it when they can simply say they do not play it because it sent a bad message? (Alternatively, perhaps they would make it shorter?)

Recordings of the complete Guangling San from Shen Qi Mi Pu24

(in addition to my own and

these others)

Around this time Guan Pinghu was doing his work several other players also did reconstructions; there are some significant differences, but the similarities suggest they were either consulting each other or the others were largely following Guan's lead. The recordings by these other masters were not at first publicly released, but they can now be found in several compilations made since 2016. Later recordings do not use silk strings. For the eight listed here their timings link to the recordings.

Complete recordings from the 1950s:

Complete recordings not using silk strings include:

After the Cultural Revolution ended, Guan Pinghu's version was re-released and the piece entered the conservatory repertory, but always in abbreviated versions, ranging in length from 6 to 13 minutes, usually closer to the former. As such it subsequently became one of the most popular in the current repertoire, with at least 20 recordings available. The complete recordings by Wu Jinglue and his son Wu Wenguang came out later.25 And in 2006 Hugo released a CD that included Xu Lisun's complete version, as above.26 The version by Yao Bingyan recorded and transcribed by Bell Yung is incomplete, but again his complete version is linked above.27 More recently there have been recordings that stop after Section 27 (the end of the Main Sounds division).

My interpretation of Guangling San: was it a

"dapu"?28

Regarding my own version, which can be heard

linked below as well as on one of

my CDs, this was the first melody I tried to learn in 1976, right after I left Taiwan. I then had no teacher, so I began learning it by following as best I could the recording then available from Guan Pinghu, and a photocopy of the transcription into staff notation linked above. Eventually, however, I began working directly from the original tablature, which led to my developing some important differences of interpretation. The three main focuses of this work have been,

Acoording to my understanding, then, when I began by simply copying the transcription and recording of Guan Pinghu's interpretation, this was not dapu. The subsequent work, however, do fit into such a definition.

Expressing the true significance (志) of Guangling San

(+)

When playing Guangling San, and especially while memorizing it, I have often had the following structural outline in mind (as well as the more detailed comments on each division linked with each one). Associating this outline with specific motifs helped me to remember the whole without having constantly to refer to the tablature. But although this structure is still in the back of my mind as I play, I can point to few specific musical phrases connected to specific themes in the titles or story. And further to what I mentioned above, I do not see the music as a sort of tone poem giving specific details of a story. It is more a metaphor for emotions that perhaps are also in line with what one learns from reading the essays and poems of Xi Kang.

Back to dapu: in general, for me reconstructing music from old tablature is rather like trying to see into an ancient world. It might be said that this is an attempt to give that world meaning. But putting that meaning into words recalls the old saying that if you can put it into words, then it won't be the true meaning (i.e., 名可名非常名 from the Dao De Jing). How enjoyable, then, is it to feel you can express it in music?32

Original Preface

33

The Emaciated Immortal, in accordance with Qin History,

34 says,

"At a time when Sima Yi was a high-ranking general (in the state of Wei), Xi Kang and Zhong Hui35 were senior palace scribes. Whenever Zhong Hui had contact with Xi Kang, Xi Kang did not bother to act politely towards him. Zhong Hui hated him for this, so he made slanderous comments that Xi Kang had wanted to help (a military action by General) Guanqiu Jian36 (to try to restore power to the Cao clan). Since Sima Yi was an intimate, he believed Zhong Hui and destroyed (Xi Kang).

"When Xi Kang was about to be executed at (Luoyang's execution ground, see

illustration), the East Market, he looked around at the scenery, took out his qin and played it, saying, 'Formerly Yuan Xiaoni37 (wanted to) study Guangling San from me, but I never would part with it; so Guangling San will no longer exist after today.' At this time (Xi Kang) was 40 years old. All gentlemen within the seas were sore at heart, and when the emperor finally investigated and learned the truth, he was regretful."

Later (Yuan) Xiaoni was able realize the meaning of "taking a rest",42

and spun it out to make the eight sections (of Hou Xu).

These are the 41 sections. (Xiao) Xu (division two,

with three sections also called Zhi Xi) was brought in separately.

The world scarcely knows about this."

Return to top

1.

廣陵散 Guangling San references

(廣陵 Guangling and 散 San are discussed separately below)

Modern sources include:

The work of Manfred Dahmer

Both volumes have bright yellow covers and are listed on Amazon; I have the 2009 volume but have only seen the transcriptions from the 1988 volume.

2.

Slacken Second String Tuning (Manshang Diao) (慢商調 11385.xxx)

Here diao refers to tuning rather than mode, the directions being to man shang: slacken the second string from standard tuning, so that it has the same pitch as the first string. This tuning is found only in versions of Guangling San. Slackening the second string so that it is the same as the first string facilitates rhythmic repetitions of the same note over these two strings.

In addition, the five strings of the qin are said to represent aspects of society, as follows.

Thus by making the second string have the same pitch as the first string, it is said to symbolize the equality of the master and his vassal. In traditional society many qin players objected to the melody for this reason, but in modern times it led to claims of political correctness.

As for the modal qualities of Guangling San, the main tonal center (based on phrase, section and division endings) is strongly on do (1; gong); secondarily on sol (5; zhi), but often phases end going from re (2; shang) to do. These are the characterestics of Shen Qi Mi Pu shang mode melodies; in addition, the first two divisions have numerous

flatted 3rds, also a characteristic of many shang mode melodies. For more on mode see

Modality in Early Ming Qin Tablature, in particular modal characteristics.

3.

Painting by Bai Yunli; see details.

4.

散 San-type melody

5.

廣陵 Guangling

6.

Origins of the melody Guangling San

Unfortunately, though, tracing the origins of melodies based solely on their occurrence as titles is of limited value with regard to the melodies themselves. This perhaps can be seen most starkly in trying to connect the three differing stories and four melody titles discussed under

Shui Xian Qu (see also

this footnote).

Such also seems to be the case with the mentionings of Guangling Sanin the Yuefu Shiji

Mentions of Guangling San in

Yuefu Shiji (YFSJ)

However, although titles such as these are mentioned in the following essay by Tong Kin-Woon, I have not yet found mention anywhere in YFSJ of some of the references he does mention. These include,

Also, while at the beginning of YFSJ Folio 41

(Xianghe Ge Ci 16) there is mention of Guangling San (saying it is no longer transmitted), this does not seem to connect to what is written here by Dr. Tong.

These shortcomings on my part should be kept in mind when reading Dr. Tong's essay, partially translated here.

"Guangling San", an essay by

Tong Kin-Woon

(pdf of original)

Discussing this simply, Guangling was a folk song already existing in the Spring and Autumn period. During the Han Wei period it was formed into a "相和歌 Xianghe Ge" (instrumental melodies with accompanying lyrics;

mentioned here?) in 楚調 Chu mode. Because of 旋律可賞 its admirable melody it was also formed into a "但曲 Dan Qu" (a purely instrumental melody, not using song), and it could be played connectively (for example, serving as a part of the Six Playings melody set), or played by itself.

Guangling originally used a variety of instruments played together. It is not known when it developed as a solo qin melody, but the book (? 書 !) Qin Cao by

Cai Yong, describing the qin melodies with which he was familiar, has in the section Hejian Zage a melody called Nie Zheng Kills the Han King.... (Translation not finished.)

This story from Qin Cao is discussed above. Here Dr. Tong's article is quite long and its references difficult to follow. For example, I found reference to

"綿駒遺謳 Legacy Ballad of Mian Ju" in what is apparently commentary on a statement about Mian Ju ("昔者王豹處於淇,而河西善謳;緜駒處於高唐,而齊右善歌....") in 孟子,告子篇 the chapter Gaozi in the book of Mengzi), where it says,

However, I am not sure of the date or significance of that quote.

7.

Xi Kang and Nie Zheng?

In reading this very interesting article I was trying to see how it would affect my thoughts as I play the melody (my current thoughts on this are outlined here). If I understand the article correctly, Prof. Ding thinks the surviving melody does date back to Xi Kang, but in Xi Kang's hand it had a totally different theme, one more in keeping with his own natural character. The Nie Zheng story must thus be a later addition.

Although Prof. Ding does not seem to present historical evidence connecting the surviving melody to whatever it was that Xi Kang played, he seems to support quite well his argument that the melody would originally have been much less connected to violence.

In light of all this it is interesting to see the following video of a recording of the first four divisions of Guangling San by his daughter 丁霓裳 Ding Nishang:

You can see Ding Chengyun himself sitting in front and facing his daughter. Does this suggest that Prof. Ding is not suggesting changes in play, only in interpretation? Does he consider the slackened thirds in the score to be Song dynasty additions, and so changing them to major third intervals is a way of returning to the original?

8.

Zhi Xi 止息: Stop for a Breath. Also: Hold one's breath? Stop breathing?

These seem to have nothing connected to music or to the present story. Although its literal meaning is "Stop - Rest", it is tempting to try to connect it to the Nie Zheng story. For example, if he was just "taking a breath", why was that significant? Or did Nie Zheng hold his breath when he was about to attack? Does it mean he stopped the King/minister from breathing? No such translation would be justified based on the three examples just given.

How, then, did "Zhi Xi" come to be used as a subtitle for the Small preface (小序 Xiaoxu)? For more on this see Hui Zhi Xi Yi as well as Yuan Xiaoni, the Guangling Zhi Xi mentioned above, and also further related commentary such as here.

Another title, 報親曲 Bao Qin Qu (Report to Ancestors) is used

here.

9.

Nie Zheng Stabs the Han King (Qin Cao: 聶政刺韓王 Nie Zheng Ci Han Wang; see

translation)

However, although the present Guangling San clearly takes its story from Nie Zheng Stabs the Han King, there is no hard evidence showing a musical connection between the surviving melody and any melody that might have been played in the third century.

As for the association with 蔡邕

Cai Yong and his

Qin Cao, note that there are

two competing versions of this title:

Cai Yong is also sometimes credited with having created the qin melodies Chang Qing and

Qiuyue Zhao Maoting, was well as being associated through his daughter Cai Wenji with the melodies Xiao Hujia and Da Hujia.

11.

Early instrumental versions of Guangling San

12.

Variety in surviving versions of Guangling San

The accompanying article by Wang Shixiang includes a very interesting comparative analysis of these three earliest versions. He concludes that the Shen Qi Mi Pu version is the earliest. Of particular note, he points out the more complex right hand techniques unique to the 1425 version; such emphasis on the right hand is very rare in later music. Unfortunately he does not seem to be aware of the issue of flatted thirds, as mentioned below and discussed further here. The use of both flatted and whole tone thirds in a melody was an ancient characteristic, and a closer study of its use might help date melodies with that characteristic. At present, however, one can only say that it is a characteristic found in melodies that claim origins, varyingly, in the Tang and Song dynasties, but that it could also be a characterstic coming from the Yuan dynasty. (For the possibility of Yuan influence one would want to know about the modality of Yuan opera and how that might have influenced Chinese music in general.)

13.

Du Kui as teacher of Guangling San

14.

Huayang Pavilion

15.

會稽 Kuaiji (or Guiji, or Huiji)

16.

Tracing the qin melody Guangling San

As for transmission since 1425, there are details below in the Appendix. As can be seen there, Zha Fuxi's index 2/11/-- lists Guangling San in 11 handbooks, but only 6 have the long version; others have only 9-11 sections.

17.

Poetry on the Guangling San theme

18.

Longest melody in the active qin repertoire

On the other hand, I am not aware of anyone other than myself currently playing a full version of Guangling San. The version in the official syllabus of Chinese conservatories

(古琴曲集) consists of only the first four divisions and most people don't even play that much, preferring shortened versions focused on the "exciting parts". In addition, there exists tablature for several other melodies with a large number of sections (such as the ca. 1802 Yuhua Deng Xian with 50!), but none is played today.

19.

Later short versions of Guangling San

The 1907 handbook has two versions. The second is said to be new; the first is mentioned in connection with ≥1802. In this regard this first version is quite similar to the first version in 1634 but it is much closer to the short one dated ≥1802 (it also has more flatted notes). The short versions generally played today are different from these.

22.

夏蓮居 Xia Lianju (1884 - 1965)

23.

Guan Pinghu recording

24.

Recordings of Guangling San

25.

Recordings by Wu Jinglue and Wu Wenguang

Wu Jinglue's son Wu Wenguang (1946- ), one of the most famous guqin players of the next generation, earned his ph.D. at Wesleyan University, writing his dissertation on music of the Wu Family; he then returned to China, teaching for many years at the Chinese Music Conservatory. His Guangling San recording did not have a general release until the ROI album was produced in 1998 on a Taiwan label.

Wu Wenguang's qin had nylon-metal strings but this 1998 recording was still based on his father's complete version (compare Wu Wenguang's later recording above).

Wu Wenguang's book The Qin Music Repertoire of the Wu Family, pp.142-176, includes this transcription. It was apparently made by Wu Wenguang based on his father's performance. Wu Wenguang's own performance is largely based on this version, but he says he did not try to follow it too closely, lest it inhibit his own style.

26.

Xu Lisun recording

27.

Yao Bingyan recording and transcription

28.

My interpretation of Guangling San: is it a dapu?

Reconstruction of Guangling San and its political considerations

![]() 22'29";

one of three, each one with a few differences but mostly following

this transcription [4.6 MB])

22'29";

one of three, each one with a few differences but mostly following

this transcription [4.6 MB])

![]() 18'20" (compare Wu Wenguang below; Wu Wenguang also made this transcription [10.2 MB] from the Wu family tradition)

18'20" (compare Wu Wenguang below; Wu Wenguang also made this transcription [10.2 MB] from the Wu family tradition)

![]() 20'32"

20'32"

![]() 16'59"

16'59"

![]() 20'45"

20'45"

![]() on YouTube; 15.01; fastest!

on YouTube; 15.01; fastest!

![]() on BiliBili; 24.50

on BiliBili; 24.50

![]() 30.00, but it follows Guan Pinghu; with comparative transcriptions; source)

30.00, but it follows Guan Pinghu; with comparative transcriptions; source)

Regarding "志 zhi" see "志" and "其為人" in the

famous story of Confucius learning Wen Wang Cao from Shi Xiangzi.

Sets the tone and gives a feeling for the musical mode

Still setting the tone; the three sections have a similar structure and feeling

Titles suggest a reminiscence of Nie Zheng's childhood

In three parts (chronology depends on switching three titles):

(Sections 10-17): Preparing to get revenge; end with slow reminiscence and vow

(Sections 18-24): Do the deed; the music should be more aggressive

(Sections 25-27): His "exemplary" sister gives him his credit

Titles seem randomly ("luan") to recall scenes from the story: a positive honoring of his life?

Titles refer to emotions from the story but not in a discernable order; in the music there are repeated motifs. A celebration of his life?

(See 原序 the original and also 其他早期源材料

other related early Chinese texts.)

Music (Timings follow my recording: 聽錄音 Listen;

看五線譜 See transcription;

also:

看視頻 Video w/transcription [2 GB];

Zoom recording;

Links to recordings by eight others

Six divisions and 45 sections: 44

plain version

(00.00) (no subdivisions)

(similar to the later modal preludes)

一名移燈就座 Yi ming Yi deng jiu zuo also called Move the lamp then sit49

Exchange the titles of 22-24 with those of 25-27?

(22.06) Postscript ends

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

9693.181 廣陵散 Guangling San: 琴曲名 qin melody name. It begins by telling the story of Xi Kang learning the melody at 華陽亭 Huayang Pavilion. It then quotes

Other early sources of note include:

Earliest melody introduction; or is it?).

Tells of Xi Kang playing Guangling San at his execution, though at least one related version (文士傳 Wen Shi Zhuan) identified the melody as "太平引 Tai Ping Yin" (Melody of Grand Peace; also see 1907).

- Chapter 2.B. (Nie Zheng Ci Han Wang Qu,

中文 pp. 19-20;

- Chapter 3.B. (Guangling San,

中文 pp.30-36).

Manfred has written two books in German focused on Guangling San:

This book seems basically to be his doctoral dissertation on Guangling San. It includes:

This book seems to have much more general information about the guqin. This includes:

(Return)

There is no separate title here for the melody in Slackened Second String Tuning: it is written under the title for Guangling San.

(Return)

(Return)

13567.0/14 says this refers to the qin melody Guangling San. V/472-3 gives some further musical connections, but neither entry suggests san could mean something like 曲 qu (melody). For this see the

essay by Tong Kin-Woon below.

(Return)

9693.178 廣陵 Guangling first mentions 江都 Jiangdu, near modern Yangzhou in Jiangsu province, but it also mentions several other places including 息縣 (10855.80) Xi district east of 信陽 Xinyang in southeastern Henan (described as 常為兵爭之地 often a battleground). Near here the tomb of a 楚 Chu prince has been unearthed, yielding sets of stone chimes.

(Return)

The sophistication of the melody written down in the earliest surviving written tablature, in the 6th or 7th century for the melody Jieshi Diao You Lan, suggests there might have been a long tradition of such tablature, but that longhand tablature is quite cumbersome and in any case the music was at that time certainly a largely oral tradition. Quite likely there would have been many versions of any even relatively popular melody, but if any were written down they have not survived.

This Song dynasty collection of ancient lyrics and titles mention Guangling San in at least three folios

This ballad does not seem to be in YFSJ; 28343.84 has only Mian Ju, adding nothing

Mentioned in connection with 李延年 Li Yannian (d. 82 BC;

Wiki), said to have edited this melody and made it one of the Six Playings (六彈 Liu Tan; 1477.xxx; 彈 10085.xxx), but compare this list of seven songs.

Published in 廣陵散對話 Guangling San Duihua, pp 32-4. The booklet, for a 1989 Taiwan performance, also includes photographs of some famous qin as well as informaton about the program and performers. The essay, which refers seveal times to Yuefu Shiji (as above) begins as follows:

In the Western Han the famous music master Li Yannian said, "Legacy Ballad of Mian Ju" is the xiantiao (string-drum?) "Guangling".

(Return)

What might be the correct story to accompany the melody Guangling San is discussed in considerable detail in the article 《广陵散》本末辨正 Guangling San Analyzed and Corrected from Beginning to End, by 丁承運 Ding Chengyun of the Wuhan Conservatory of Music, originally published in 《音乐研究》2022年第2期 Music Research, 2022, Volume 2

(online). Here Professor Ding argues that the attribution of the melody to Xi Kang is incompatible with the melody telling the violent story of Nie Zheng: associating the latter story with Guangling San is something that happened during the Song dynasty. More specifically, he provides evidence that the Guangling San associated with Xi Kang is the perfect embodiment of his musical thought about the qin (as expressed by "聲無哀樂論 Music has neither grief nor joy" and "養生論 Discussion on Nourishing Life"), and the speific explanations in his "琴賦 Rhapsody on the Qin" about the word "散 san" and the title "止息 Zhi Xi" (connecting it to Daoist meditation).

(Return)

16609.58 止息: "停息休止 stop breath rest stop". It has numerous quotes:

(Return)

8/xxx; 29829.22 聶政鼓琴 Nie Zheng Plays the Qin quotes the

Hejian Zage section of

琴操 Qin Cao (2nd c. CE?; Hejian Yage has "Guangling San" but no commentary) in relating the story given here; note that it does not mention cao as in the title 聶政刺韓王操 Nie Zheng Ci Han Wang Cao Melody of Nie Zheng Stabbing the Han King. At this time the Han kingdom had its capital in what is today Luoyang.

(Return)

See the TKW article as mentioned above.

(Return)

Of particular note is the fact that the three surviving versions in the two earliest handbooks (Shen Qi Mi Pu [1425] and Xilutang Qintong [1525]; see appendix) have almost identical section and division titles and two are musically very similar, but one is very different; then the later full versions simply copy rather than re-interpret the earlier one. Studying the differences could be very instructive for understanding the development of qin melodies and music in general. One of the versions in 1525 seems to be a close re-interpretation of the 1425 melody, while the other 1525 version seems to be a new melody inspired only in part by the 1425 or another older one. This suggests they date from a time the melody was actively played. The later copies, being identical, provide no evidence that the melody was actually played by the compiler - or anyone at that time. It is also perhaps noteworthy that neither of these other two long versions seems to have the

flatted thirds found in the 1425 edition, discussed further in the next paragraph.

(Return)

Again see TKW, 1989. Xi Kang is also said to have studied with the famous hermit Sun Deng 孫登, learning some tunes from him, but apparently not Guangling San

(Return)

31910.272 華陽亭 says it is in 河南新鄭縣東南 the southwest part of Xinzheng district of Henan province (south of modern Zhengzhou), adding a different reference from Jin Shu, but still identifying it with Xi Kang; Luoyang was also in Henan, west of Xinzheng. (See also next).

(Return)

The interpretation that the travel was from Luoyang home is speculation based on the understanding from the above footnote that Huayang Pavilion was on one of the possible routes from Luoyang, where Xi Kang lived, to Kuaiji, his family's ancestral home. The main

Kuaiji references under

Yu Hui Tushan are to Shaoxing, or a region centered on Suzhou but including Shaoxing. There is also a Kuaiji mountain in Shandong. However, there are no apparent references to Henan or Anhui (where Xi Kang was actually born), hence this comment remains speculative.

(Return)

The transmission of Guangling San is examined in the article by Wang Shixiang translated here, as well as in the article by Tong Kin-Woon partially translated above.

(Return)

This includes poems by

Yelü Chucai,

Lou Yue and

Xu Zhao.

(Return)

This is a complicated issue, depending on definition of terms. Thus,

my recording of the Shen Qi Mi Pu melody Qiu Hong is 20'20' compared to 22'06" for my Guangling San, but these are close enough that changes in tempo could reverse the relative lengths. The second version of Guangling San dated 1525 is presumbably also about the same length, but to my knowledge no one has played that in recent history.

(Return)

"Short version" does not refer to the popularly-played abbreviated interpretations of the old 1425 melody. These are new short versions that first appear in 1634 with a melody that has been attributed either to its compiler, 潞王朱常淓 the Prince of Lu Zhu Changfang, or to a noted qin player at the time, 金陵汪安侯字子晉

Wang Anhou of Nanjing, also known as Wang Zijin. Shiyixianguan Qinpu (1907). has an extended essay on the how Wang Anhou became connected to a short Guangling San.

(Return)

Xia was also himself a qin player. See further on

guanglingsan.com.

(Return)

The recording is available in a number of collections including Favourite Qin Pieces of Guan Ping-hu (both the

2 CD 1995 set and the

4-CD 2016 set); An Anthology of Chinese Traditional and Folk Music: A Collection of Music Played on the Guqin, Vol. l, China Records, 1994. (老八張; Timing: 22.22). I originally worked with a photocopy of the transcription into staff notation linked above. The actual pdf copy here was made from the book with the 2016 4-CD set. From this 張世彬 Zhang Shibin did a transcription into Chinese number notation; Tong Kin-Woon published this in his Qin Fu, pp. 2775-2800.

(Return)

As mentioned, the listing here includes only complete versions; it also includes only recordings made with silk strings. To my knowledge there have been no recordings of any of the other early versions, of any sort.

(Return)

Wu Jinglue (1907 – 1987) is discussed further here; his recordings of Guangling San were included in several collections, including the two listed here.

(Return)

Mei An Qin Music; Hugo HRP 7257-2 (HKG, 2006); timing: 17.06

(Return)

Bell Yung, Celestial Airs of Antiquity, A-R Editions, Inc.

(Wisconsin, 1997, CD published together with a book of

transcriptions; Guangling San; 15.07 [omits Xiao Xu, Luan Sheng and Hou Xu])

(Return)

As discussed above I did not learn Guangling San directly from tablature, I learned it first by copying the recording and transcription by Guan Pinghu, only later revising it based mostly on re-examining the original tablature, including my understanding of what the section titles were intended to convey. According to the account here this makes it a sort of modified dapu.

(Return)

| 29. Old symbols and techniques difficult to interpret | 倚涓? - 喚 - 換 |

These four images have examples of techniques with varying interpretations, none of them easy to follow.

These four images have examples of techniques with varying interpretations, none of them easy to follow.

- 倚涓 yi juan? (left image at right; see further). This is the basic symbol; it is copied there because my computer cannot re-create it (it is written something like 奇 but with 立 replacing 大 on top and 厶 replacing the 口 inside).

- 倚涓 yi juan (second image from left) on the fifth and sixth strings with the thumb at the fourth position. This is the symbol as it appears, doubled, in the original Guangling San tablature. The explanation was both hard to find and ambiguous, hence there are differing interpretations. In the present Kai zhi, which seems to be a sort of prelude to Guangling San, it is the fourth and fifth figure (cluster; see my transcription, mm. 3-5). It is also a cluster that Guan Pinghu's reconstruction made in the 1950s interprets as (with the left thumb at the 4th position) 摘 zhai the 5th and 6th strings then 涓 juan both strings, repeated: 6+6 notes in all; all subsequent interpretations other than my own seem to follow this. However, there is no such figure in old finger explanations, so I have interpreted it (see transcription) as a simple yijuan: Hand Aspect Illustration #10 writes yijuan as 倚㳙 (with 立 again replacing (大) and interprets it as 半㳙 ban juan: half a juan, with only two notes. This interpretation thus results in only 2+2 notes. Yi juan also appears again later in the melody (e.g., mm. 317 and 343).

- 奐 huan (third image from left); by itself "abundant".

One reference (V/159)

says this is short for 喚 (also huan: summon);

another (I/97 and referenced here) says it is 換 huan (12709), usually meaning "exchange". When applied to the right hand, 換 huan is used for techniques that require separate use of more than one finger. As a left hand technique (as at the beginning of Guangling San), it is explaned as a type of slide, perhaps down and up. My own interpretation has been that here it is 喚, a left hand technique it is a sort of

turn.

三作 san zuo (bottom of third image from left): by itself, "do three times". However,, in addition to the question of whether this means "do what came before a total of three times" or "repeat what came before three more times", in some old pieces in particular it may not be clear what is to be repeated. Thus, in the example at far right where the instructions after "三作 play three times" say "大日勹" (i.e., "大閒勾 da jian'gou", a multi-stroke technique involving 5 notes ), Guan Pinghu's interpretation is to repeat both the two preceding notes (one of which is ornamented with the huan) and the 5-note technique, making 21 notes in all, three of which have ornamentation. My interpretation is to repeat only the two precending notes then add the 5-note technique, making 11 notes in all, again three ornamented. - 換三指 san zuo with "小閒勾 xiao jian'gou" (right image at right). At the top of the second cluster, without stating the position to be played, the tablature indicates three left-hand fingers (人中夕 means index, middle and ring fingers respectively). My interpretation is that right hand index finger "乚 kicks out" on the open 七 seventh string three times, alternating with the right index finger "打 hitting inward" on the 五 fifth string in the 10th position (this position suggested by context) while the three indicated left fingers 換 in turn stop the fifth string (a technique that requires each of the respective left fingers to slide up into the position. After these six notes there is a 小閒勾 xiao jian'gou that adds three more, making 9 notes to here. The initial six notes are then played again but this time it is followed by a 打閒勾 da jian'gou adding this time 5 more notes to make 11 notes. The described passage thus has 20 notes in all. No other interpreter seems to play the passage this way: the transcription of Guan Pinghu's interpretation shows 33 notes here while that of Wu Wenguang shows 29 notes.

In addition, many stroke techniques here are not only difficult to distinguish, they are repeated in ways that make it easy to confuse them. For example, 蠲 juan on string 1 is two notes and juan on strings 1 and 2 is four notes, but is the sequence 1 1 2 2 or 1 2 1 2 (which would be like a "全扶

quan fu", but this technique rather surprisingly does not appear in Guangling San)?. In this regard, when I originally learned the piece I tried to keep this all straight. Eventually, though, I came to the conclusion that it was more important to use a variety of these techniques than to remember exactly where and how they occur in the tablature.

(Return)

30. Non-pentatonic notes (see also modal characteristics

above and below)

Traditional Chinese music is said to be pentatonic, with melodies always following the scale do re mi sol la (today usually written 1 2 3 5 6).

When I first learned Guangling San in 1976/7 I simply followed the interpretation by Guan Pinghu, in which he "corrected" almost all the notes that as written were non-pentatonic. However, after reconstructing many melodies from Shen Qi Mi Pu I noted that most non-pentatonic notes occurred with a logic that made it clear that they actually were intentional. So I then re-did my interpretation, playing the notes as written instead of continuing to follow Guan's changes.

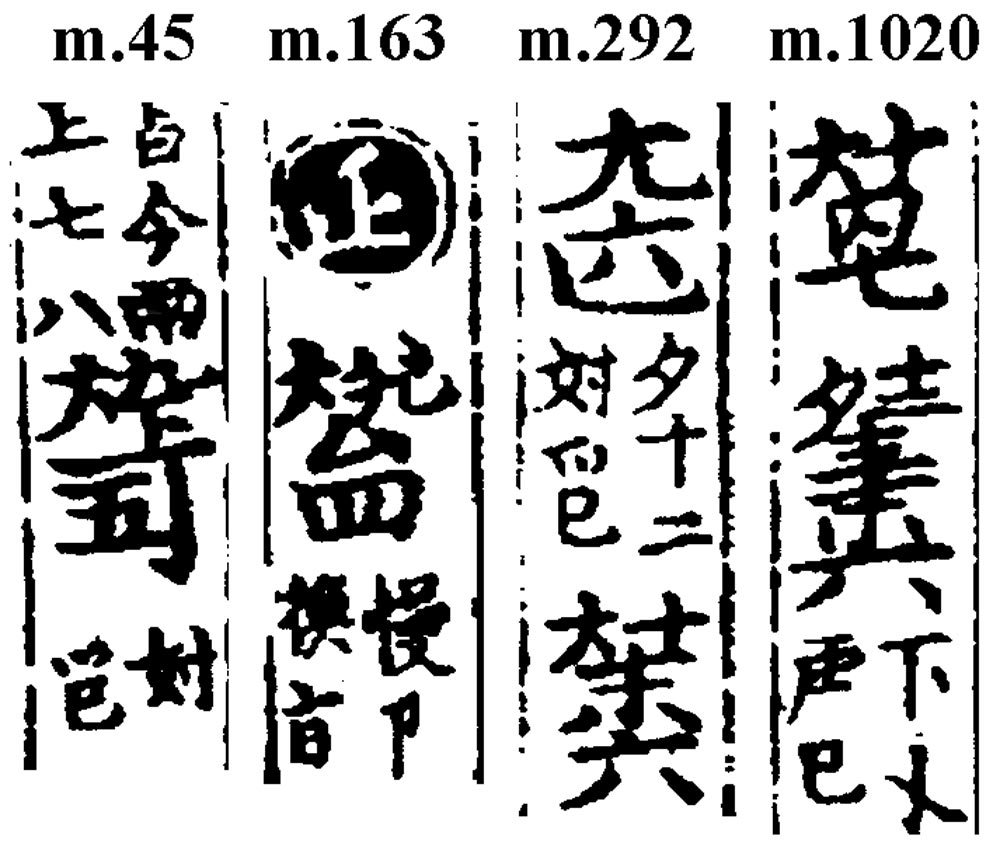

By far the most common non-pentatonic notes in Guangling San are flatted 3s, 4s (fa), and 7s (both flatted and unflatted). In modern reconstuctions of Guangling San the most commonly changed notes are the flatted 3s. Specifically the original versions are here in my transcription; four are shown at right:

- Section 1 (mm. 18?; 28)

- Section 2 (m.45, 九下 on 五 at right)

- Section 4 (m.114)

- Section 6 (mm. 163, 八九 on 四 at right; 174)

- Section 8 (m.272)

- Section 9 (m.292, 十二 on 六 at right)

- Section 34 (m.962, 十二 on 六 at right)

- Section 37 (m.1020).

Note that flatted 3s are perhaps even more common in the 1634 short version, though not the other non-pentatonic notes.

In none of the recordings linked above do the players play the flatted thirds. As for the flatted and unflatted 7s, these are less likely to be changed. And although they are not listed here, it has been my observation that, while there are both flatted and non-flatted 7s throughout, the outer divisions seem to have fewer of the non-flatted 7s. The significance of this is also unclear.

(Return)

31.

Changing modality of the six divisions of Guangling San

Interestingly, the flatted thirds listed in the previous footnote all occur in the opening two divisions and again in division five. This is particularly interesting because of the argument by Wang Shixiang that the central divisions of the surviving melody are the most ancient, perhaps even dating from before the Tang dynasty. He also seems to suggest that the sectionsi in the outer divisions were gradually added during the Tang and/or later. Is it significant that these flatted thirds not seem to occur in You Lan,

and yet this is a modal characteristic often found in SQMP pieces (particularly those like Guangling San using a shang mode).

This characteristic continued to be found in other early- and mid-Ming dynasty handbooks, then it gradually disappeared. According the Zhu Quan, the compiler of Shen Qi Mi Pu, he was trying to rescue the qin by reviving melodies he had found from sources apparently from the Song dynasty. Could it be that flatted thirds and other characteristics specific to such melodies as these include characteristics specific to the Song dynasty?

To my knowledge at that time there had been no research done comparing the modality of these divisions.

In this regard see also the comments and links above under Man Shang Diao.

(Return)

| 32. Expressing meaning | Nie Zheng's sister claims his body (Sections 22-24) |

The image at right concerns the "exemplary woman": it is said to be from the

新刊古列女傳八卷 New Printing of the Old

Biographies of Exemplary Women (#107 中文). Because it shows Nie Zheng's sister (姊 jie; see 別姊

Extraordinary sister [1955/5: 決也, as in 別材、特別]), this is the story from Shi Ji and does not include guqin, but it can still be used as an example in studying how something might be expressed not just in art but in music. It clearly relates to Guangling San Section 22-24 (烈婦、收義、揚名 ), the title of 23 literally translated as "Reveal (her brother's) righteousness" and clearly showing Nie Zheng's sister claiming his body so that his virtue will become known. The scars on Nie Zheng's face relate to the part of the story told in Section 24 and in both

Shi Ji and

Qin Cao, where he cuts his face so that people would not recognize him and hence harm his family. The third person in the room presumably is an official. Notice, though, the sister's apparently calm demeanor. Modern depiction would probably have her holding out her chest heroically and perhaps raising her fist in defiance. Here does she have no emotions, or does this show the sister was holding back emotions that are clear to anyone who knows the story? When I play the music for this section I feel it must be the latter (listen).

The image at right concerns the "exemplary woman": it is said to be from the

新刊古列女傳八卷 New Printing of the Old

Biographies of Exemplary Women (#107 中文). Because it shows Nie Zheng's sister (姊 jie; see 別姊

Extraordinary sister [1955/5: 決也, as in 別材、特別]), this is the story from Shi Ji and does not include guqin, but it can still be used as an example in studying how something might be expressed not just in art but in music. It clearly relates to Guangling San Section 22-24 (烈婦、收義、揚名 ), the title of 23 literally translated as "Reveal (her brother's) righteousness" and clearly showing Nie Zheng's sister claiming his body so that his virtue will become known. The scars on Nie Zheng's face relate to the part of the story told in Section 24 and in both

Shi Ji and

Qin Cao, where he cuts his face so that people would not recognize him and hence harm his family. The third person in the room presumably is an official. Notice, though, the sister's apparently calm demeanor. Modern depiction would probably have her holding out her chest heroically and perhaps raising her fist in defiance. Here does she have no emotions, or does this show the sister was holding back emotions that are clear to anyone who knows the story? When I play the music for this section I feel it must be the latter (listen).

For poetry see this poem by Yelü Chucai and this poem by Lou Yue. (Details to be added after translation.)

As discussed here, understanding "meaning" in music usually involves knowing the significance of cliches used in that idiom. But what do you do when reconstructing melodies that have not been played in centuries? Following the conventions of modern (especially Western) may prove satisfactory to many but will it create the feeling (illusion) of connecting with an ancient world?

As I have discussed elsewhere, when I reconstruct a melody I first look at the musical idiom and structure, and only when I feel some comfort with that do I look closely at the meanings applied to the melody (such as through the titles, sub-titles and commentary). A problem with Guangling San, then, is that some of the sub-titles I do not fully understand, and in general many of them seem jumbled rather than being arranged in a coherent manner.

Furthermore, in discussing this, one should also consider whether it is appropriate for the music, as with poetry, to be too obvious or explicit about what it expresses. Here consider the story of Boya and Ziqi: when Boya plays a melody (most famously Flowing Streams [Liu Shui]) only Ziqi realizes what Boya is trying to express, the point being that only a 知音 knowledgeable person (this term also means "soulmate") will realize what someone is playing.

What does this say about the popularity of the 19th century (72 gunfu Liu Shui version of Liu Shui, which seems to be designed so that anyone can understand what is being expressed? Is this applying a modern standard to an ancient aesthetic?

Taking this further, when it comes to musical cliches, with Western music listeners may have an idea that there is something sad or angry or anxious going on, but not the further specifics unless someone tells them. Likewise with qin melodies.

On the other hand, if you know what the melody is about then you might be able to say, "Oh, yes, I can see/understand that." Likewise, when playing Guangling San, if you can play it instinctively enough that you don't have to think about what techniques you need to use, but instead think about what the titles say it should express, you can often think, "Yes, I can feel that there is anger (or whatever was mentioned) here", though you may not feel the anger yourself.

As a sidelight: Does this connect to the ideas of balance associated with Confucius and yin-yang? When applied to the qin, perhaps this suggests when you hear something expressing "hair raising anger" you should be able to think, "Yes, I can hear this refers to hair-raising anger and appreciate that", but at the same time I do not wish to feel this myself, because if it did it might put me out of balance."

To explore this further, watch the video from Sections 18 to 23 of my recording:

As I listen I can recall trying to play it in a way that seemed appropriate to the section titles, and now I still feel that it is in fact appropriate, though I do change somewhat the phrasing accordingly.

Similar feelings also come to me when listening to that section of Guan Pinghu's recording:

What's more, I can imagine visual imagery going with the music that would also make the music seem appropriate to the feeling. Beyond that, why should I want to hear really angry sounds? (N.B., I am also not a big fan of horror movies.)

At the same time I can also see this might not work for everyone. But then I also have to wonder whether this has to do not with the music itself but with the listener not being able to set aside innate ideas of how music should work.

33.

This preface and other original commentary

The handbooks that actually have Guangling San tablature are listed below in this chart. Here is an outline of their commentary.

《西麓堂琴統 B》 Xilutang Qintong B, 1525 (chart). An afterword (III/250, after the second version;

original text):

Mostly not yet translated.

34.

Qin History (琴史 Qin Shi)

35.

鍾會 Zhong Hui (225 - 264)

36.

毌丘儉 Guanqiu Jian

37.

袁孝尼 Yuan Xiaoni (Yuan Zhun)

38.

Qin Book (琴書 Qin Shu)

![]() Watch:

start at 9'25"

Watch:

start at 9'25"

![]() Listen: start at 10'38".

Listen: start at 10'38".

(Return)

This page has the originals of this and other related commentary, beginning with the original of the preface above. These texts were mostly copied from Zha Fuxi's Guide to Existing Guqin Pieces in Tablature, which includes a collection of all available prefaces and afterwords for all the melodies in the handbooks it indexed, plus that from some other early sources.

(Return)

The contents of Zhu Changwen's Qin Shi (Folio 3, #84 Xi Kang) is different. In some cases Zhu Quan's sources are problematic, and here it is not clear whether this refers to the name of a book or just to the history of qin in general.

(Return)

Zhong Hui (41566.123; Bio/1723; Giles) was a noted scholar/official in Wei during the Warring States period. Once rebuffed by fellow senior scribe Xi Kang, Zhong Hui became so angry that he later accused Xi Kang of treason, leading to his execution (see Gulik, Hsi Kang, pp. 29-34 as well as the above Original Preface to Guangling San

(Return)

17088.1 Guanqiu says it is a place name in Shangdong and a double surname. 17088.3 identifies Guanqiu Jian as a man of Wei during the Three Kingdoms period. (Bell Yung, op.cit. mistakenly has Mu Qiujian.)

(Return)

The biography of Yuan Xiaoni says he learned part of Guangling San, particularly Guangling Zhi Xi (see Division II.).

(Return)

See in this footnote from the Preface to Shen Qi Mi Pu

(Return)

39.

至亂聲小息 zhi luansheng xiaoxi; xiaoxi,

"small breath" (or Taking a rest) is the name of the Small Preface; another

translation could be that he got to a section of Luansheng called

Xiao Xi, but it would then be more difficult to make the numbers add up.

(Return)

41.

Yuan Xiaoni's version of Guangling San

This story, as quoted in Qinshu Daquan (1590, V/268 under Zhi Xi [see next footnote], not Guangling San), has two more phrases here: "餘七伯覓上得,故有止息 The other seven (sic) sections he couldn't do, so there was a break." See also in Qin Yuan Yao Lu.

(Return)

42.

Realize the meaning of "taking a rest" (會止息意 Hui Zhi Xi Yi)

See the title of the first section in division six,

Houxu. Regarding zhi xi itself see above. The meaning here seems to be that Zhi Xi was created by Yuan Xiaoni according to his understanding of the whole piece.

There being such differing Ming versions of Guangling San

as the one here and the two in Xilutang Qintong, combined with

Zhu Quan's mention of two versions, shows that by then Zhi Xi

was a completely integral part of the existing piece.

(Return)

43.

937 years

僅(經)九百三十九年 The calculation of 937 years seems to be in error. If the calculation is from the Jianyan period (1127-31) back to the death of Xi Kang in 262 the range is 865 to 869 years. 937 years after Xi Kang died would be 262+937=1199 CE. Wang Shixiang suggests it should be 837 years, this being the number of years from the end of the Chen dynasty (557-588) until 1425, the year Zhu Quan published SQMP. The only other possibility seems to be that he was quoting something originally written in 1199, which would have been about the time 張巖 Zhang Yan was collecting old materials that were later incorporated into 楊瓚紫霞洞琴譜 Yang Zan's

Zixiadong Qinpu.

(Return)

44.

Guangling San original titles

See also this bilingual outline for 1425 and this comparative transcription of all three.

The original of these translated titles are as follows (those from the two versions in Xilutang Qintong are added for comparison:

|

Shen Qi Mi Pu (I/112)

|

Xilutang Qintong A (III/237)

Melody is different |

Xilutang Qintong B (III/243)

Melody more like SQMP |

| I. 開指 Kai zhi

|

慢商意 Manshang Yi

(before GLS) |

慢商品 Manshang Pin

(before GLS) |

| II. 小序 Xiao xu | II. 小序 Xiaoxu | II. 小引 Xiao yin |

| 2-4. 止息 Zhi xi

|

1-3. 止息 Zhi xi | 1-3. (no subtitle) |

| III. 大序 Da xu | III. 大序 Da xu | III. 大序 Da xu |

| 5. 井里 Jing li | 4. 井里 Jing li | 4. 井里 Jing li |

| 6. 申誠 Shen cheng | 5. 申誠 Shen cheng | 5. 申誠 Shen cheng |

| 7. 順物 Shun wu | 6. 順物 Shun wu | 6. 順物 Shun wu |

| 8. 因時 Yin shi | 7. 因時 Yin shi | 7. 因時 Yin shi |

| 9. 干時 Gan shi

|

8. 干時 Gan shi | 8. 干時 Gan shi |

| IV. 正聲 Zheng sheng | IV. 正聲 Zheng sheng | IV. 正聲 Zheng sheng |

| 10. 取韓 Qu Han | 9. 取韓 Qu Han | 9. 取韓相 Qu Han Xiang |

| 11. 呼幽 Hu you | 10. 呼幽 Hu you | 10. 呼幽 Hu you |

| 12. 亡身 Wang shen | 11. 忘身 Wang shen | 11. 亡身 Wang shen |

| 13. 作氣 Zuo qi | 12. 作氣 Zuo qi | 12. 作氣 Zuo qi |

| 14. 含志 Han zhi | 13. 含志 Han zhi | 13. 含志 Han zhi |

| 15. 沉思 Chen si | 14. 沉思 Chen si | 14. 沉思 Chen si |

| 16. 返魂 Fan hun | 15. 反魂 Fan hun | 15. 反䰟 Fan hun (𠫓/鬼) |

| 17. 徇物 Xun wu

一名移燈就座 (Yi ming Yi deng jiu zuo) |

16. 徇物 Xun wu

|

16. 徇物 Xun wu

|

| 18. 衝冠 Chong guan | 17. 衝冠 Chong guan | 17. 衝冠 Chong guan |

| 19. 長虹 Chang hong | 18. 長虹 Chang hong | 18. 長虹 Chang hong |

| 20. 寒風 Han feng | 19. 寒風 Han feng | 19. 寒風 Han feng |

| 21. 發怒 Fa nu | 20. 發恕 Fa shu (mistake?) | 20. 發怒 Fa nu |

| 22. 烈婦 Lie fu | 21. 烈婦 Lie fu | 21. 別姊 Bie jie |

| 23. 收義 Shou Yi | 22. 收義 Shou Yi | 22. 報義 Bao yi |

| 24. 揚名 Yang ming | 23. 揚名 Yang ming | 23. 揚明 Yang ming |

| 25. 含光 Han guang | 24. 含光 Han guang | 24. 含光 Han guang |

| 26. 沉名 Chen ming | 25. 沉名 Chen ming | 25. 沉名 Chen ming |

| 27. 投劍 Tou jian

|

26. 投劍 Tou jian | 26. 投劍 Tou jian |

| V. 亂聲 Luan Sheng | V. 亂聲 Luan Sheng | V. 契聲 Qi Sheng |

| 28. 峻跡 Jun ji | 27.峻跡 Jun ji | 27.峻跡 Jun ji |

| 29. 守質 Shou zhi | 28. 守質 Shou zhi | 28. 守質 Shou zhi |

| 30. 歸政 Gui zheng | 29. 歸政 Gui zheng | 29. 歸政 Gui zheng |

| 31. 誓畢 Shi bi | 30. 誓畢 Sh ibi | 30. 誓畢 Shi bi |

| 32. 終思 Zhong si | 31. 終思 Zhong si | 31. 終思 Zhong si |

| 33. 同志 Tong zhi | 32. 同志 Tong zhi | 32. 同志 Tong zhi |

| 34. 用事 Yong shi | 33. 用事 Yong shi | 33. 用事 Yong shi |

| 35. 辭鄉 Ci xiang | 34. 辭鄉 Ci xiang | 34. 辭鄉 Ci xiang |

| 36. 氣衝 Qi chong | 35. 氣衝 Qi chong | 35. 氣衝 Qi chong |

| 37. 微行 Wei xing

|

36. 微行 Wei xing | 36. 微行 Wei xing |

| VI. 後序 Hou xu | VI. 後序 Hou xu | VI. 後序 Hou xu |

| 38. 會止息意 Hui Zhi Xi Yi | 37. 會止息意 Hui Zhi Xi Yi | 37. 會止息意 Hui Zhi Xi Yi |

| 39. 意絕 Yi jue | 38. 意絕 Yi jue | 38. 意絕 Yi jue |

| 40. 悲志 Bei zhi | 39. 悲志 Bei zhi | 39. 悲志 Bei zhi |

| 41. 嘆息 Tan xi | 40. 嘆息 Tan xi | 40. 嘆息 Tan xi |

| 42. 長吁 Chang xu | 41. 長吁 Chang xu | 41. 長呼 Chang hu |

| 43. 傷感 Shang gan | 42. 傷感 Shang gan | 42. 傷感 Shang gan |

| 44. 恨憤 Hen fen | 43. 恨憤 Hen fen | 43. 憤恨 Fen hen |

| 45. 亡計 Wang ji | 45. 亡計 Wang ji | 45. 忘計 Wang ji |

45.

Opening fingering (開指 Kai zhi; Division 1, Section 1; a modal prelude, not mentioned in Table of Contents)

Kai zhi seem to have been modal preludes to specific melodies, as opposed to the more general diao yi which, at least in Ming dynasty handbooks, are modal preludes that always occur at the beginning of a set of melodies that use that mode. For another "kai zhi", with further information, see #12, Kai Zhi. For an especially problematic finger technique used here see Old symbols, while for the use here of flatted thirds see non-pentatonic notes.

The end of the Kai zhi here is marked "吉冬" instead of one of the ending indicators used elsewhere in SQMP, namely,

"意冬" (意終 yi zhong: modal prelude ends)

"扌冬" (操終? cao zhong: piece ends)

"周冬" (調終 diao zhong: melody ends)

"曲冬" (曲終 qu zhong: tune ends).

Not having found an explanation for "吉冬" my tentative interpretation is that "吉" is short for "結", thus, "結終 jie zhong" means "conclude-end". However, another possibility is that "吉" is short for "周" (i.e., 調). In SQMP "吉冬" occurs also at the end of Ling Xu Yin, Shan Ju Yin,

Huang Yun Qiu Sai and

Zepan Yin.

Perhaps strangely, each of the other five divisions of Guangling San ends in "畢 bi" ("end", thus "小序畢 Xiao Xu ends", etc.). So can this be used as part of the argument that the Kai Zhi in SQMP was added later? In this is it significant that the other Kai zhi also ends in "畢 bi" ? Unfortunately, the jumbled nature of this data means it does not seem to provide a quick clue in trying to determine the relative ages of melodies or parts of melodies.

(Return)

46.

Small preface (小序 Xiaoxu; Division 2, Sections 2-4): Stop for a Rest (止息 Zhi Xi)

16609.58 止息 has nothing connected to music. There is some further detail above under Zhi Xi as well as examples under

Yuan Xiaoni, and

Guangling Zhi Xi, but even the further related commentary such as here does not resolve the issue of what precisely was meant here by "止息 Zhi Xi". Once again, although literally it means "stop - breath", the various possibilities mentioned above include "stop for a breath", "hold one's breath" or even "stop breathing", i.e. "die".

(Return)

47.

Grand preface (大序 Daxu; Division 3, Sections 5-9)

It has been suggested that this division reflects on the youth of Nie Zheng.

For "因時" there is only 4796.36 "因時運", which says, "晉鼓吹曲名 name of a Jin era wind and percussion piece".

For "干時" 9369.44 says "求合於當時也 search for what is appropriate for the times"; also "= 扞 han: protect" .

(Return)

48.

Main Sounds (正聲 Zheng Sheng; Division 4, Sections 10-27)

16611.449 正聲 discusses correct and appropriate sounds; esp. see ref. to Shen Gua 沈括 .

The 18 sections of Zheng Sheng seem to be the heart of the piece. In addition, or perhaps because of this, there seems to have been an effort made for them to be chronological - and they would be quite chronological if the titles (not the music) of Sections 22-24 were reversed with those of 25-27. Zheng Sheng would then pair nicely with the Grand Preface, which speaks of Nie Zheng's earler life. In this case, Zheng Sheng seems naturally to fall into three parts:

1- 8: prepare for action, then review options before deciding to go ahead

9-15: carry out the deed then try to protect family

16-18: reveal the truth about this

Section titles of note include:

9: 衝冠 Chong guan: 34894.16 "為冠冕被衝起也 cap lifted up", the example (Shi Ji 81) saying this was caused by hair raised in anger)

10: 長虹 Chang hong: 42022.333 "rainbow, long bridge" suggests grandeur, but bravery?

Section 30 is noteworthy for its repeated motif of plucking the open first and second strings inward then outward. Played slowly, could it suggest a death knell?

(Return)

49.

Move the lamp then sit (移燈就座 Yi deng jiu zuo)

25606.xxx; 8/81xxx. About this I have seen some speculation that says the night before Nie Zheng was to avenge his father he moved the lamp to sit and contemplate what had led him to what he was about to do.

(Return)

51.

Concluding Sounds (亂聲 luan sheng; Division 5, Section 28-37)

220.153 亂聲 defines luan sheng as "雜亂之聲音也 mixed sounds".

However, because "luan" can also mean "tidy up a mess",

"luan sheng" has came to be used for the final section/division of a music piece. On the other hand, the titles of the 10 sections here seem to come in an almost random order, appropriate to interpreting "亂聲" as "miscellaneous sounds". Most sections end with the motif of plucking the open first and second strings inward then outward. This motif is also found earlier, see in particular measure 30, where it seems to suggest a death knell. Here, however (also in the next division) it seems to call for faster playing, making it perhaps more a sound of praise [this interpretation from Xu Jian]).

(Return)

52.

Postscript (後序 Hou Xu; Division 6, Sections 38-45)

This division is often considered to have been a later addition. For more on this, search for "Hou Xu" in Wang Shixiang's article, in particular this chart. The article includes a suggestion that this whole division perhaps should be seen as (if not called) "Hui Zhi Xi Yi": "explaining the meaning of "zhi xi", i.e., why it is an alternative title for the whole melody.

Meanwhile musically, as with the previous division this final one has a number of short sections, mostly ending with the repeated motif of the first and second strings, usually but not often open strings. There are also a number of phrases that would normally be played in harmonics but here are played with stopped sounds, giving a special effect.

Again, Xu Jian suggests that the music in this section is intended as a celebration of Nie Zheng's deed, or an homage to his life.

(Return)

Appendix: Chart Tracing existing Guangling San tablature

For earlier transmission see above

This chart is based mainly on Zha Fuxi's Guide, 2/11/--. He lists it in 11 handbooks, but only 6 have the long version; others have only 9-11 sections.

|

Qinpu 琴譜

date; vol # / page # |

Those aligned left are related to the Shen Qi Mi Pu version

|

|

1. 神奇秘譜

(1425; I/112) |

45: Kai zhi + 3 + 5 + 18 + 10 + 8; no phrasing indicated

|

|

2.a. 西麓堂琴統 (A)

(1525; III/237) |

1 (Manshang Yi) + 44 (3 + 5 + 18 + 10 + 8); no separate commentary;

transcription

still musically related, though often seeming completely different from 1425 |

|

2.b. 西麓堂琴統 (B)

(1525; III/243) |

1 (Manshang Pin) + 44 (3 + 5 + 18 + 10 + 8); afterword still no phrasing indicated;

transcription

closer to 1425 but many changes in both section titles and music (e.g., loses flatted thirds) |

|

3. 風宣玄品

(1539; II/198) |

45: Kai zhi + 3 + 5 + 18 + 10 + 8; no phrasing indicated (seems identical to 1425)

No commentary |

|

4.a. 古音正宗 (A)

(1634; IX/382) |

"廣陵真趣 Guangling Zhenqu"; "慢商調開指 Manshang mode Kai zhi";

1 section; "Guangling's True Essence": a prelude, only here, seems mostly unrelated to 1425 |

|

4.b. 古音正宗 (B)

(1634; IX/382) |

廣陵散 Guangling San; 9 sections (? at end it says "廣陵真趣九段終 end of Guangling Zhenqu 9 Sections!);

"by Xi Kang", but little connection to 1425; ≥1802B seems based on this (see changes) |

|

5. 琴苑新傳全編

(1670; XI/443) |

= SQMP;

no phrasing indicated |

|

6.a. 裛露軒琴譜 (A)

(≥1802; XIX/352) |

= SQMP;

no phrasing indicated |

|

6.b. 裛露軒琴譜 (B)

(≥1802; XIX/363) |

廣陵真趣 Guangling Zhenqu; 10 (1st, "首段", is harmonics from 1634 #1);

中文;

"中聲手訂 personally edited by Zhongsheng (?)"; although title is like 1634A, melody is rather different (see changes; original pu) |

|

7. 蕉庵琴譜

(1868/XXVI/108) |

10;

pu almost same as ≥1802 B

comments at front of sections are also very similar, but no general preface |

|

8. 希韶閣琴瑟合譜

(1890; XXVI/458) |

10; has afterword;

like ≥1802 B but more differences and adding paired se tablature |

|

9. 琴學初津

(1894; XXVIII/401) |

10; "黃林變調...lowered second string"; pu very similar to ≥1802 B, but see end;

afterword has section comments and long preface that mentions 臞仙, i.e., Zhu Quan |

|

10.a. 十一絃館琴譜 (A)

(1907; XXIX/5) |

"廣陵散 真趣 Guangling San True Essence"; 10;

"閩中雲在青較 as revised by Yun Zaiqing" and "金陵汪安侯演正 played as corrected by Wang Anhou of Nanjing"; also credits Xi Kang but says 潞藩(王) Prince of Lu version (1634); pu same as ≥1802; section comments similar but at end of sections; comparisons; 中文 |

|

10.b. 十一絃館琴譜 (B)

(1907; XXIX/12) |

"廣陵散新譜 New tablature for Guangling San; 10;

listen to recording by Chen Changlin;

"New" here means it was revised (edited?) from the "authentic version"; can follow section by section |

|

11.a. 琴學叢書

(1910; XXX/245) |

"= 1868"

(but compare 1634); 10; also QF/1013;

has new system that indicates rhythm (see page 1) |

|

11.b. 琴學叢書

(1910; XXX/428) |

"= 1539"; preceded (419ff) by finger explanations and further commentary;

not included in the 琴府 Qin Fu edition; has new system to indicate rhythm (see pages 1 and 2) |

Return to top, to the Shen Qi Mi Pu ToC, or to the Guqin ToC.

Appended comment

If someone says they like something that I am unable to appreciate or understand, I might question them, but in general is it not good when everyone has their own artistic tastes and prejudices? Workers songs for the guqin? Concertos for guqin and orchestra? Pop music with guqin? Why not?

When it comes to guqin it is good to hear people experimenting with all sorts of new music. Some of it I quite like but with guqin my natural inclination is towards the old music: by playing old music directly from the tablature I can never get enough of it. Based in part on its seemingly endless variety, my own prejudice is that it is better than the new music. But this is indeed just a prejudice, and not something I want to enforce on others.

At the same time I am happy to recount how one of the things that has drawn me to guqin is that by playing music according to my understanding of the principles of historically informed performance (HIP) I can at times imagine I am somehow getting a unique, perhaps direct, insight into the world of some amazing people who lived centuries if not millenia ago. But for this I need certain triggers.

A good example of this is recordings of the melody 廣陵散 Guangling San. Modern recordings are usually abridged versions, often following the Chinese conservatory standard, which is about seven minutes long. Some of these sound wonderful, well deserving their high regard. But at the same time I find them all somehow unsatisfying.

Is it because of my Western perspective that hearing a 7 minute version of such a classic seems to me rather like hearing a version of a Beethoven symphony where the orchestra is only looking for the highlights?

Likewise, the metal string conservatory interpretation may be very evocative, and certainly many people think that it allows them to get into the aesthetic world of the people who created the melody. I cannot do so: I can only appreciate it as what seems to me: clearly a modern take.

For me, much of the attraction of this piece comes from playing (or listening to) the entire melody on the instrument that was used to create (silk string guqin); related to this, if I like a melody I then always enjoy it when I can follow up on the art and commentary that it has inspired.