|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry

/ Song |

Hear / Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| The Qin and the Chinese Literati Qin influence on behavior and nature | 中文 目錄 |

| Qin Ideology 1 | 琴道 |

Traditional attitudes towards the qin are often said to have been more Daoist than Confucian (rarely Buddhist6) but writings about the effects of the qin on people's behavior show a mixture of these philosophies. In addition, a study of qin melodies shows Confucian themes to be almost as prevalent as Daoist themes.7 Thus, as Zhu Quan states in his preface to Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425 CE):

As the qin became a physical object, the sages made it in such a way that it could correct purposeful thoughts, provide leadership in worldly affairs, bring accord to the six influences and tune the harmony of the seasons. It is indeed the divine instrument of heaven and earth, and a most ancient spiritual object; thus it became the music used by sages of our Middle Kingdom to control the government, and the object used by princely men to cultivate (themselves); it is only appropriate to stitched sleeves (i.e., scholars) or yellow caps (Daoists).

The best English language source for guqin ideology is R.H. van Gulik, Lore of the Chinese Lute (2nd ed.); Tokyo and Rutland, Tuttle, 1969.

The article by James Watt suggests that by the Qing dynasty the common approach to the qin was changing. If this is true, perhaps it was related to the expansion of merchant culture. As part of this, books became much more widely available, art forms such as opera became widely popular, and these led to literati culture and ideas being reinterpreted by whole new groups of people.8

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Qin ideology (琴道 Qin Dao)

"Qin Dao" literally means "Way of the Qin", and many will argue that "Qin philosophy" is a better translation than Qin ideology; it is actually a combination of both and in that way not either one.

(return)

| 2. A stringless qin | Another stringless qin |

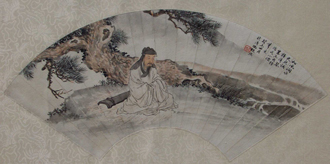

The image above (expand) shows a fan painting, entitled Nature's Melody, by 馮超然 Feng Chaoran (1882-1954). The image at right,

called 采鞠 Cai Ju (采菊 Picking Chrysanthemums) from the Honolulu Museum of Art, shows the most famous expounder of that idea, Tao Yuanming.

The image above (expand) shows a fan painting, entitled Nature's Melody, by 馮超然 Feng Chaoran (1882-1954). The image at right,

called 采鞠 Cai Ju (采菊 Picking Chrysanthemums) from the Honolulu Museum of Art, shows the most famous expounder of that idea, Tao Yuanming.

Further relevant comments about qin music as nature's melody can also be found here:

- A story about Bo Ya and his teacher Cheng Lian, related here in connection with the Water Immortals' Melody (水仙曲 Shuixian Qu).

- The reality around playing qin in nature.

- Tangentially, the idea of music beyond sound

- Also tangential, the famous couplet by Tao Yuanming that says if you already understand the inner significance of the qin there is also no need actually to play it.

The idea of qin music as nature's melody (天然調 tianran diao) is related to attitudes about the natural materials used in qin construction (epitomized by its silk strings) and extends to cosmological connections often cited. The idea suggests that when already surrounded by the sounds of nature there is no need to play qin: qin music is just another form of nature's melody. This is also expressed in poems about so-called "wind-qin" or "wind-se", in which music is created by wind blowing through trees (examples), especially bamboo or pine (松濤 songtao; examples).

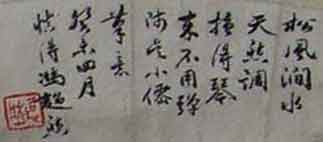

The full original inscription from the image above is as follows:

陟星(?)小僊筆意。癸未四月。 (The first two characters are unclear; see also below)

慎得馮超然。(圖寫﹕)超然」 (Feng Chaoran, style name Zhende; [the seal says] "Chaoran".)

The couplet at the front of the inscription expresses sentiments found in poetry at least as early as Seeking Seclusion by Zuo Si (3rd C. CE; q.v.). The couplet itself also can be found often (e.g., see at the end of a long poem from a collection called 繪事徽言 in 四庫全書補正 Corrected Siku Quanshu (online, p. 237); there are several variations for the first half, including 「松風澗響天然韻」 and 「高山流水天然調」.

The first two characters after the couplet might be 陟星 zhixing ("ascending the stars"); 小僊 Xiaoxian was also the nickname of the famous painter 吳偉 Wu Wei (1459-1508). The date is then stated as 癸未四月 April 1943.

After this is apparently a nickname 慎得 Zhende, then the painter's proper name, Feng Chaoran (1882-1954); the seal says 超然 Chaoran. Feng was quite well known and a number of his paintings can be found on the internet

3.

Playing for an imaginary one: a personal ideology

Elsewhere Prof. Yung writes of dapu only as a creative process whereby a qin player plays a new piece inspired by the original; he says one should not try to reconstruct the way it was originally done because that is impossible. To me, however, that could be said of any teacher: I could never copy my original teacher exactly. Now my teacher is the old tablature I am working on. I try to learn as much as I feel I can from that teacher before going on and studying with another one. Having learned more, though, I will quite likely come back later to the earlier teachers.

A standard view of the "creative dapu" approach is that players absorb the essence of a melody then go on to create their own version. My own approach to absorbing this essence is perhaps somewhat different, perhaps determined by the fact that I am an outsider: being aware I am a modern person rather than a Ming dynasty literatus makes it more difficult for me to believe I have truly absorbed the essence. This essence includes not just the philosophical and/or ideological outlook of the music's creators, but also their instincts about the musical structure. This is not something mentioned much in old texts; but see, for example, how often rhythm is mentioned in

Shilin Guangji. So far this approach has continued through my reconstruction of over 300 melodies. When could it ever be time to say I have absorbed enough essence?

A related question is, Should musicians simply express what is in their mind, or should they keep in mind their audience? As is recommended in old qin books, I enjoy sharing music with like minded people. Thus, although usually my audience may seem to be just myself, in my mind I am trying to communicate with the people of ancient times who created the music. It is a continually rewarding experience.

4.

Playing qin vs praying for forgiveness

5.

Qin influence on nature and on human behavior

Potential benefits of the qin are said to include:

(return)

In his article "An Audience of One: The Private Music of the Chinese Literati", Bell Yung "argues that in playing privately, the player turns inwardly toward himself rather than outwardly toward an audience." The article gives a good outline of this important aspect of qin ideology. Here I suggest that it is also interesting to consider the possible differences between such players simply expressing what is in their minds, and them imagining they are communicating with someone else. Here I am particularly concerned with the latter concept. When I reconstruct (dapu) and then play an ancient melody, I often imagine myself trying to communicate with those who

created and originally listened to it. What affect does this have on the music I play? Am I simply deluding myself? (I cannot claim great insights from this: often such thoughts go little beyond, "What kind of strange/amazing people could have created music as exceptional as this?")

(return)

There has long been debate about the Chinese equivalents of the concepts of sin and forgiveness as found in the Abrahamic Religions

(Wikipedia). See, e.g., the Wikipedia entry

Chinese views on sin. I have little to add to this here except to wonder what a traditional Chinese equivalent would be to the Christian practice of, after a day spent in sin (whatever the interpretation of that is), going home, getting down on your knees and asking God for forgiveness. After an evening of carousing might Ming dynasty literati have gone home and played a bit of qin in their studio or boudoir in an effort to center themselves (align themselves with the universe) before getting to bed?

(return)

Proper behavior involves various concepts, most of them rather difficult to translate. Such terms include,

Righteousness (義 yi, also "morality");

see Dasheng Yueshu reference and

qin name

Moral integrity (節操 jiecao);

see comment on Qin Cao

Rectify, bring order (正 zheng, as in "正人心 zheng the mind/heart"); see Baihu Tong

Ritual (禮 li); see references in the

Book of Rites

Body at rest and mind at peace

Control the universe (天下治 tianxia zhi; i.e., bring the world in line with the way it should naturally be; Fengsu Tong)

The sentiments expressed above by Zhu Quan carry this further. The Chinese original is:

(return)

6.

Buddhism

Buddhist ideas seem to be important mainly for the ways they may have affected Daoist and Confucian ones. For more on Buddhism see Buddhism and the qin.

(return)

7.

It has sometimes been claimed that when a Chinese literatus succeeded in attaining a government position he followed the structures of Confucianism, but when he lost his position he became a Daoist, achieving all by doing nothing.

(return)

8.

Changing qin ideology

Here one can point to several noticeable but not clearly divided trends:

- Prior to the Han dynasty the qin was generally treated like any other instrument. The stories depicting qin as having a special position in society were mostly created starting in the Han dynasty.

- Xi Kang's 4th century Rhapsody on the Qin might be seen as a confirmation of the status of qin over all other instruments, but it is difficult to know how this came about. Was it important that the qin was intimate as well as portable? Is it significant that this intimacy also made it more difficult for ordinary people to access, so it was therefore less likely to be debased? In any case, this status has in theory come right up to the present. But although it is difficult now really to know precisely how "pure" was the practice of qin ideology before the rise of the commercial class during the mid to late Ming dynasty, clearly the attitudes were quite different then.

- Coming up to the modern period, as is made clear in James Watt's article, commercialisation gradually crept into the refined world of the literati. Today the information on pages such as The Qin in Popular Culture: Novels and Opera is available to us because the emerging media of that time has given us a fuller picture of attitudes in these later periods.

At the same time, these media clearly had a significant impact as they emerged. For example, printed handbooks only became widely available well into the Ming dynasty. Then, as a result, the guqin's "music of the ancients" became much more widely accessible. Today through recordings one can hear how this affects actual qin play, but there has been little study of how changes in society affected this in the past.

Clearly, though, the role of the "timeless" qin, both in society and as music itself, has changed over time.

(return)

Return to the Guqin ToC