|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| XLTQT ToC / Prelude: Meng Ji Yin / Shrine to Shun / Silk Zither Dreams | Listen to my recording 聽錄音 / 首頁 |

|

54. Cangwu Lament

- Jue mode:2 standard tuning 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 |

蒼梧怨 1

Cangwu Yuan A lady contemplates Cangwu, from Kuian Qinpu 3 |

"Though Emperor Shun said, 'Through non-action one governs,'

"Though Emperor Shun said, 'Through non-action one governs,'

he died in Cangwu." The Analects 4

Although this melody is ostensibly a lament by two wives over the death of their husband, Shun, an orthdox Confucian interpretation has it also as a lament by people mourning for their ruler, and for the fact that he died as he toiled away for them in a remote region (here Cangwu, also known as Jiu Yi or Jiuyi Shan, a southern wilderness area now part of Hunan, near the Guangdong border).5 In connection with this, two other titles need to be considered:

Cangwu Yin (Cangwu Prelude),7 another related title, survives in five handbooks from 1596 to 1692. The title suggests it could have been a prelude to Cangwu Yuan; instead, except for the first occurrence (which is related to Liang Xiao Yin!), it is an alternate version of Cangwu Yuan.

Further regarding Meng Ji Yin and its use here as a prelude to Cangwu Yuan, the theme of a widow who has lost her husband does give the two a logical connection. However, since the title Meng Ji Yin and its melody survive only here, where there is no separate commentary, it is difficult to say with certainly what its true origin was. For example, was it created specifically as a prelude to Cangwu Yuan, and if so when? Was it an independent melody borrowed for use here? Was the melody here ever explicitly connected to the Book of Songs lyrics?

As for Cangwu Yuan itself, it can be found in at least 16 surviving handbooks. Adding the four related Cangwu Yin makes 20 publications of this melody from 1525 through 1876, with 14 of them published before 1700. A preliminary examination suggests quite a few variations until 1689, after which it had a much more stable form.8

On the other hand, if the Xilutang Qintong afterword (see below) is correct, in 1525 the melody was already very old. The "Old man Zixia" mentioned there must be Yang Zuan, a famous collector of qin melodies and the center of a group of famous qin players in Hangzhou during the 13th century. Yang Zuan is said to have collected old tablature into a handbook called Zixiadong Qinpu (Handbook of the Rosy Haze Grotto).

It should be added that Cangwu Yuan relates the same story as does another qin melody, Xiang Fei Yuan.9 The latter, a song more specifically in the voice of Shun's two widows, survives in 13 handbooks fr0m 1511 and is still played today, but the two pieces are musically unrelated. This story is also the subject of many poems.10

All the handbook commentaries on Cangwu Yuan are consistent with the story outlined above: the melody tells of the two daughters of Emperor Yao, E Huang and Nü Ying,11 lamenting the death of their husband, Shun (2317?-2208? BCE), after he passed away in Cangwu. Cangwu is an old name for a mountainous region of southern Hunan province, near the border with Guangdong. Here, at a town called Jiuyi, there is a temple commemorating Shun.12

According to Annal 1 of Shi Ji,13 Shun grew up at Guirui in what is today Shanxi province.14 Having heard that through filial actions Shun was able to keep harmony in his family, Yao gave two of his daughters to Shun in marriage, observing how well he treated them. When Shun was 50 years old Emperor Yao made him head of state, naming him his successor. When Shun was 58 Yao died, and three years later Shun became emperor. When he was 100 he traveled south on an inspection tour, dying while in the wilderness of Cangwu. He was buried across the river at Jiuyi.

At Jun Shan island15 near Yueyang, a city in Hunan province on the eastern shore of Dongting lake, there is a temple in honor of E Huang and Nü Ying, including their supposed grave. They are said to have cried so hard at Shun's death that their tears speckled the bamboo near his grave. Speckled bamboo is native only to an area near Yueyang in northern Hunan.16

The distance from Jiuyi to Yueyang is over 500 km. In addition, Yueyang is on the northeast side of Dongting lake, while the Xiang river flows into the southern side. I am not sure how issues such as how the sisters heard of Shun's is resolved in the related stories.17

More stories about Yao's two daughters are outlined below. Both the elder, O Huang, and the younger, Nü Ying, are associated with the Xiang River goddesses mentioned in several Chu Ci poems.18 One tradition says that the third of the Nine Songs is addressed to the older, the fourth to the younger.

Music

The 1525 Cangwu Yuan (#54) is the main piece of a suite that also includes a modal prelude, Jue Yi (#52), and a melodic prelude, Mengji Yin (#53). Thus the music for all three is linked here together.

One Section; goes with the following two melodies (see transcription p.1; timing follows my recording 聽錄音)

00.40 harmonics

00.58 end

Music of Mengji Yin

Three Sections; comes after Jue Yi

(see transcription pp.2-4; timings follow my recording 聽錄音)

00.50 2.

01.18 3.

01.42 harmonics

01.59 end

Music of Cangwu Yuan

(Twelve sections;20

comes after Jue Yi and Meng Ji Yin

(see transcription pp.4-14; timings follow my recording 聽錄音)

00.51 2. Tearing at one's hair while wailing and weeping 22

01.22 3. Sad gibbering of bereft gibbons 23

01.59 4. A solitary snow-goose is alarmed

02.21 5. Profound separation

03.02 6. Sighs arise whether awake or asleep

03.45 7. Cherishing thoughts of Guirui

04.18 8. In the wild seeing Chonghua (Shun)

04.58 9. Tears cleanse bamboo along the Xiang river

05.22 10. Spirits freeze on the mountaintops of Chu

06.01 11. The mists come together over the Jiuyi mountains (of Hunan)

06.49 12. Deep clouds over the Seven Marshes (i.e., Chu24)

07.28 harmonics

07.42 end

(The levels on this recording are unbalanced to the left and too low.)

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Cangwu Yuan 蒼梧怨 (QQJC III/127)

Cangwu literally suggests the dense foliage of wu trees. For more on wu trees see wutong, a wood commonly used for making qin tops. However, dictionaries seem to refer to Cangwu mainly as a geographical term (see Cangwu below). The 1525 afterword also clearly uses "Cangwu" as a place name, though see the commentary with the Kuian Qinpu illustration.

(Return)

2.

Jue Mode (角調 Jue Diao)

In jue mode the primary note is equivalent to the open third string, called jue. In addition the secondary tonal center is the note jue (mi, 3). Like Xiang Fei Yuan (shang mode), Cangwu Yuan is one of the few Chu theme melodies to use standard tuning. For more on jue mode see Shenpin Jue Yi of 1425; for mode in general see Modality in early Ming qin tablature. Both this modal prelude and #54 Meng Ji Yin (see below) seem to be directly connected to Cangwu Yuan itself. In fact, these three (#53-55) seem to be a set.

#53, Jue Yi itself, as a modal prelude, does not have its own commentary; its melody is clearly related to that of Shenpin Jue Yi of 1425 (q.v.).

Precedes Meng Ji Yin

Compare other jue modal preludes.

(Return)

3.

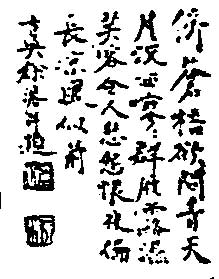

Illustration: A lady contemplates Cangwu (see Cangwu Yuan in Kuian Qinpu; QQJC XI/31)

The illustration by 徐澹 Xu Dan (or Tan; Bio/xxx; commentary by Wu Zhao mentions his name but gives no further information) shows someone gazing into the distance; a servant stands nearby, holding a qin. Almost invariably in such illustrations the people are a male scholar and his 琴僮

"qin boy". However, here the person in the scholar's position is a woman, perhaps alluding to the story of the wives of Shun. The inscription in the upper right corner (see closeup below), as reprinted in QQJC, is not very clear. It seems to say,

Leaning under the dense foliage of a wu tree, wanting to make enquiries to heaven. The moon is sinking in the west, fewer are the flocks of geese, dew dampens the hibiscuses, causing grief and resentment. Regret that the evening is so long. The breeze returns as before (?). Xu Dan of old Suzhou also added comment (to his illustration)."

The use of cangwu (for more on which see the footnote above) to refer to "the dense foliage of a wu tree", as with the depiction of a single female qin player, perhaps indirectly alludes to the story of Nü Ying and E Huang, but the commentary with the illustration seems to make no direct reference to the story. (Return)

4.

"If there was anyone who ever ruled through non-action it was Shun 無為而治者其舜也與"

This quote, from Lun Yu, 15/5, is the source of the quote above, which is from "The 'Final' Valedictory Edict" of the Kangxi emperor as found in Jonathan Spence, Emperor of China; New York, Vintage Books, 1988; p. 171.

(Return)

5.

Cangwu 蒼梧 (and the Shun Memorial there)

32425.112 蒼梧 says Cangwu is: 1. a district in Guangxi; 2. a commandery in Guangxi; 3. a mountain in a. Jiangsu and b. Hunan (also called 九疑

Jiu Yi); 4. a road in Guangxi. Only 3.b. is identified with Shun. (9/507 does not have cangwu.) There are some details here in connection with information about a memorial to Shun recently constructed in these mountains (see also the Shun Temple mentioned below). This seems to be the area closest to Hong Kong with a connection to the title of an old qin melody.

(Return)

6.

蒙棘引 Meng Ji Yin (Covered Brambles Prelude; see

music)

#54, Meng Ji Yin (32287.xxx; 32287.120 蒙棘 Meng Ji by itself; Guide 19/--/-- : only here), as a prelude to Cangwu Yuan, does not have its own commentary, and the original commentary with Cangwu Yuan does not mention brambles. Thus, the connection made above and below between Cangwu Yuan and the words "蒙棘 meng ji" in verse 2 of the lyrics of 葛生 Ge Sheng (Cloth-Plants Grow; full text below) must be considered as educated speculation.

For 蒙棘 meng ji, 32287.120 gives only the one brief reference, to the first line of verse 2 (below), a poem said to be about or sung by a woman mourning her deceased husband or lover. Since Cangwu Yuan is a lament by two concubines about the death of their husband, Shun, this might seemm to be a logical connection. Note, however, that in the first line of verse 1 the cloth-plant covers not brambles (蒙棘 meng ji), instead covering thornbushes (蒙楚 meng chu; 32287.xxx); this adds another level to the puzzle as to why the meng ji was chosen for the title.

The following is my adaptation from Arthur Waley's translation (see Book of Songs, p. 108) of the poem Ge Sheng, which he sometimes calls Widow's Lament, with sections entitled The Cloth Plant Grew (compare ctext, with translation by James Legge):

- 葛生 Cloth-plants Grow)

- 葛生蒙楚、蘞蔓於野。

予美亡此、誰與獨處。

Cloth-plants grow till they cover a thorn bush;

Bindweed spreads all over the wild.

But my lovely one is here no more.

With whom am I? I sit alone.- 葛生蒙棘、蘞蔓於域。

予美亡此、誰與獨息。

Cloth-plants grow till they cover the brambles;

Bindweed spreads across the borders of a field.

But my lovely one is here no more.

With whom am I? I lie down alone.- 角枕粲兮、錦衾爛兮。

予美亡此、誰與獨旦。

Horn-shaped pillows so beautiful, (or: wood pillows inlaid with horn?)

Brocade coverlets so bright!

But my lovely one is here no more.

With whom am I? I am alone till dawn.- 夏之日、冬之夜、百歲之後、歸於其居。

冬之夜、夏之日、百歲之後、歸於其室。

Summer days, winter nights —

Only after my shole life

Can I join him where he dwells.

Winter nights, summer days —

Only after my whole life

Can I join him in his home. - 葛生蒙棘、蘞蔓於域。

These lyrics cannot be sung with Mengji Yin following the traditional pairing method.

The melody precedes that of Cangwu Yuan

(Return)

7.

蒼梧引 Cangwu Yin (Cangwu Prelude)

Zha's Guide 28/22/-- lists the title 蒼梧引 Cangwu Yin in five handbooks, dated 1596,

1609,

1634,

1647 and its copy in

1692. From the title, one would expect it to be a prelude to Cangwu Yuan, but it has no musical relationship to the 1525 prelude, Mengji Yin. Instead, all but the first of them (1596) are in fact versions of Cangwu Yuan (see next). As for the first version (see the 1596 ToC), it is an unrelated short melody, apparently the original version of the Liang Xiao Yin otherwise dating from 1614; see the footnote there.

(Return)

8.

Tracing Cangwu Yuan (see also the previous footnote)

Zha's Guide 19/184/-- lists the title 蒼梧怨 Cangwu Yuan in 14 handbooks from 1525 to 1876, but there are several more not included in Zha's Guide; to these should be added the four related Cangwu Yin. These four plus at least 11 of the Cangwu Yuan were published in the 17th century. Thus, only six of 20 versions were published after 1700. The dates of all of these (18 entries plus two not it Zha's Guide) are as follows:

- 1525 (12 sections; begins with open notes then harmonics passage, ending mixes harmonic and stopped sounds; III/127)

- 1609 (Cangwu Yin; 14 sections; begins with harmonics; only two harmonic notes near end; VII/187)

- 1614 (13+1; begins as 1525 but ending is like 1609; VIII/106)

- 1620 (15, begins like 1525 but ends like 1609; IX/41)

- 1625 (lyrics [古聖人,不先侈富...]; 13+1; opens in harmonics, ending mixes harmonic and stopped sounds; IX/180)

- 1634 (Cangwu Yin; 10; very different: opens in harmonics, last note is stopped plus harmonic diad; IX/320)

- 1647 (Cangwu Yin; 13; opens like 1525 but ending has fewer harmonics; X/110)

- 1660 (13; opens and closes as previous; XI/31)

- 1673 (13, opens and closes as previous; X/368)

- 1689 (13+1; opens as 1525;

harmonics closing ends with stopped plus harmonic diad;

Section 2 begins earlier and all later versions seem to follow this one; XIV/237) - 1691 (13+1; like 1689; XII/524)

- 1692 (Cangwu Yin, same as 1647)

- 1692 (13+1; like 1689; XIII/79)

- <1700 (13+1; like 1689; XIV/126)

- 1722 (13+1; like 1689; XIV/459)

- 1722 (13+1; like 1689; XV & facsimile/II)

- 1726 (13; ??; XV)

- 1802 (13+1; like 1689; XVII/465)

- 1876 (13+1; XXV ["from 1802"])

- 1876 (14; ??; XXI)

(Return)

9.

湘妃怨 Xiang Fei Yuan

This melody, also called 湘江怨 Xiang Jiang Yuan and 二妃怨 Er Fei Yuan, is still played today. 18223.27 Xiang Fei says that this refers to the two wives of Shun. The earliest extant version of this melody dates from 1511. As with Cangwu Yuan it is one of the few Chu theme melodies to use standard tuning: it is generally grouped under shang mode. No version of Cangwu Yuan has lyrics, but Xiang Fei Yuan always has them (" 落花落葉落紛紛 ....").

(Return)

10.

Poems on the theme of the Wives of Shun

There are lyrics for all of the Xiang Fei Yuan qin melodies (they usually begin "落花落葉落紛紛 ....") as well as for the Cangwu Preface (蒼梧引 Cangwu Yin), a melody published in 1625 (see under Tracing). None of these is related to any of the lyrics in Yuefu Shiji

Folio 57 (pp.825-8), detailed

elsewhere, and

Cangwu Yuan never has lyrics.

In addition, 劉長卿 Liu Zhangqing, whose poem Xiang Fei is in Yuefu Shiji, also wrote a poem that mentions Cangwu (not yet translated):

蒼梧千載后,斑竹對湘沅。

欲識湘妃怨,枝枝滿淚痕

The poem Parting from Afar (遠別離 Yuan Bieli) by Li Bai also concerns this story:

海水直下萬裡深,誰人不言此離苦。

日慘慘兮雲冥冥,猩猩啼煙兮鬼嘯雨。

我縱言之將何補,皇穹竊恐不照余之忠誠。

雲憑憑兮欲吼怒,堯舜當之亦禪禹。

君失臣兮龍為魚,權歸臣兮鼠變虎。

或言堯幽囚,舜野死,

九疑聯綿皆相似,重瞳孤墳竟何是。

帝子泣兮綠雲間,隨風波兮去無還。

慟哭兮遠望,見蒼梧之深山。

蒼梧山崩湘水絕,竹上之淚乃可滅。

My tentative translation is as follows:

They were south of Dongting near the Xiao and Xiang riverbanks.

Sea waters go down ten thousand miles deep,

who cannot say their parting (from Shun) was not bitter.

The sun miserable, clouds murky,

gibbons howling in the mist, ghosts moaning in the rain.

Why would I speak of it?

Heaven (the imperial dome) would not consider this loyal.

Clouds so majestic want to roar in anger.

Yao then Shun passed on their power to Yu.

A lord may lose his minister, a dragon may become a fish,

Power may return to the minister, and a rat become a tiger.

Some may speak of Yao's imprisonment (?),

or Shun's death in the wilds (of Cang Wu, aka Jiu Yi).

Jiuyi peaks are endlessly the same,

and the emperor looks out from his lonely tomb to where?

The emperor's daughters cry amidst the green clouds,

buffeted by winds and waves they leave never to retun.

Weeping in grief while grazing afar,

looking into the depths of Cangwu.

Cangwu Mountain will collapse, the Xiao and Xiang will stop flowing,

and the tears on bamboo will be extinguished.

(Return)

11.

E Huang and Nü Ying

The dictionary references to Nü Ying (女英 6170.135) and E Huang (娥皇 6487.7) are mostly from the

Lienü Zhuan and other later sources; see also Xiangjun (湘君 18223.30) and Xiangling (湘靈 18223.86). Chu Ci has a poem about the Xiang River goddesses, apparently predating their identification with the wives of Shun. It was during the Ming dynasty that their name was given to a species of speckled bamboo. See also Anne Birrell, Chinese Mythology, p.167.

(Return)

12.

舜廟 Shun Temple in 九嶷 Jiu Yi (also 九疑 Jiuyi)

There is a 九疑 Jiuyi (25° 21' N by 112° 05' E) on modern maps in the 寧遠縣 Ningyuan district of Hunan province; some of these maps show a Shun Temple here. Nearby are the 九嶷山 Jiuyi Mountains (which also have a

Shun Memorial). The source of the 瀟水

Xiao river is also near here.

(Return)

13.

史記 translation in GSR I, pp. 8 - 16.

(Return)

14.

Guirui 媯汭

"Guirui" (6888.4) is sometimes translated Bend in the Gui River; sometimes Gui and Rui are considered two rivers. They (or it) flowed from 歷山 Mount Li, where Shun farmed, into the Yellow River in southwest Shanxi province. (Mount Li is featured in such qin melodies as Si Qin Cao,

Li Shan Yin and

Geng Lishan.)

(Return)

15.

君山 Junshan

17777.56 says an alternate name for Jun Shan is 洞庭 Dongting. David Hawkes (see below) translates 君山 as Goddess Island and 湘君 Xiang Jun as Goddess of the Xiang.

(Return)

16.

Speckled Bamboo of Junshan

There is an image of speckled bamboo under

Xiang Fei Yuan, as well as a link to a related site. These images are also appropriate for the present melody, see in particular the title of Section 9.

Junshan is also noted for a special type of green

tea called Junshan silver needle (君山銀針 Junshan Yinzhen).

(Return)

17.

Birrell, op.cit., quotes a source saying E Huang and Nü Ying lived at Dongting mountain, "a further 120 leagues southeast" from Dongting lake.

(Return)

18.

See David Hawkes, trans., The Songs of the South, p.104f, etc.

(Return)

19.

蒼梧怨 (English)

虞皇南巡,堯二女從之,升遐蒼梧之野,遂葬焉。二女倚竹而泣,皆漬成斑,後人有此曲。宋紫霞翁加訂正之,真神品也。

(Return)

20. The original Chinese section titles are:

- 鳳駕追從

- 攀髯號泣

- 斷猿淒語

- 孤鵠驚魂

- 幽冥相隔

- 寤寐興嘆

- 有懷媯汭

- 恍覿重華

- 淚浣湘筠

- 神凝楚岫

- 九疑煙合

- 七澤雲深

(Return)

21.

Phoenix carriage: 鳳駕 47631.199: chariot for an emperor or an immortal.

(Return)

22.

攀髯 pan ran 13204.28 "喻悲悼人 suggests wailing for someone", then quotes Shi Ji #28, Feng and Shan sacrifices (RGH II/37). 髯 ran (whiskers) seems to refer to men; compare 鬢 bin, which could be a woman's sidelocks.

(Return)

23.

斷猿 Bereft Gibbons: 13929.139 says this is a qin melody mentioned in

Pipa Ji.

(Return)

24.

4.453 七澤 (Qize) says 在湖北省竟內 within the borders of Hubei; it then refers to 雲夢七澤 (43170.576 a marsh in 安陸 Anlu district, northeast of Wuhan). It quotes 子虛賦 Rhapsody of Sir Vacuous by Sima Xiangru (see Knechtges translation of Wen Xuan, II/55: "I have heard that Chu has seven marshes, but I have seen only one of them....). The quote seems to suggest that Qize evokes the old Chu region.

(Return)

Appendix: Closeup of Kuian Qinpu inscription

Here is a closeup of the inscription to the right of the illustration above:

Return to the top or to the Guqin ToC.