|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Melodies Handbooks Players Other areas Performance Themes My Performances My Repertoire | 首頁 |

| Qin Melodies connected to Nanjing 1 | 南京古琴 |

| And surrounding region?2 | Playing qin in Nanjing's Purple Mountain?3 |

Nanjing's connection with many qin songs as well as instrumental melodies allows a Nanjing program to select from a large number of melodies, both purely instrumental and with lyrics. Nevertheless, existing qin tablature includes only a few melodies with themes specifically connected to the city (see below). Thus, a performance of qin melodies associated with Nanjing must focus on music from handbooks and players connected in some way to the city rather than on melodies that directly concern the city and its environs.4 It would be particularly interesting if these melodies could be presented in such a way as to show clearly definable Nanjing characteristics. Indeed, claims have been made for the existence of a Nanjing qin school (usually called Jinling School, after an old name for Nanjing). However, to my knowledge it has never been clearly defined.5

Nanjing has particular relevance to the study of qin songs:6 many such songs were created and/or published here. These songs seem particularly to have appealed to amateur qin societies and to female qin players. This and related issues are further discussed on this website under such topics as The Qin in Popular Culture: Novels and Opera anWomen and the Guqin.

It should also be noted that Matteo Ricci spent some time in Nanjing, making the acquaintances of numerous literati. One possible outline for the program Music from the Time of Matteo Ricci imagines an "elegant gathering" where Jesuits and literati exchange melodies that could have been in the repertoire of the Jesuit musicians and the Chinese literati. Ricci apparently did take part in such gatherings, though there seems to be no record of music having been played at any of them. Nevertheless, it should be possible to organize a program focused on melodies Ricci could have heard while he was in Nanjing.7

There is a long history of qin players connected to Nanjing. Those relevant to the early history of the qin include:

Although there are qin melody titles associated with some of the persons mentioned above, the surviving versions of actual melodies of these titles cannot be reliably traced back to such a early times. Thus for actual Nanjing-related melodies one must mostly look to Ming dynasty handbooks published in Nanjing.

The early qin handbooks associated with Nanjing (some associations are tentative8) include:

The sorts of specific connections to Nanjing to be found in surviving early qin melodies from these handbooks include the following:

Beyond Shishang Liu Quan, melodies with themes even more directly connected to Nanjing include:

These two melodies were apparently created by Yang Biaozheng, whose

Chongxiu Zhenchuan Qinpu is included the above list of handbooks associated with Nanjing.12 However, I have not yet reconstructed them, nor to my knowledge has anyone else done so yet.

Information about famous later qin players connected to Nanjing awaits further research.

1.

Nanjing Area (Wiki)

More generally speaking, historical details on Nanjing seem to be best for periods when it was (usually under another name) a capital city. The first extended period when it was a capital city was the so-called Six Dynasties Period (Wiki). These six dynasties are the first six names listed here:

See above for names of some qin players during these periods.

2.

Surrounding region

3.

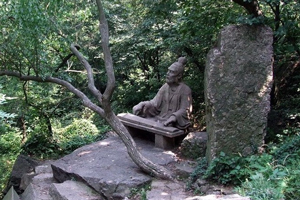

Playing qin in Nanjing's Purple Mountain?

Other qin related Nanjing images include those of the

Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove (竹林七賢圖). At least three tombs in the Nanjing area have tombs with brick relief images of the Seven Sages (or Seven Worthies). The best preserved is the one discovered in 1959 in a tomb near 西善橋 Xishanqiao, a bridge on the southwest side of Nanjing. In 1968 two similar tombs, which originally also had complete sets of images, were found at 吳家村 Wujiacun (near 胡橋 Huqiao) and 金家村 Jinjiacun (near 建山 Jianshan), in northeastern 丹陽縣 Danyang county, east of Nanjing. The Seven Sages had lived near Luoyang during the time it was capital of the Wei (220 - 265) and Western Jin (265 - 317). The tombs were built near Nanjing when it was capital of the Eastern Jin (317 - 420), Liu Song (420 - 479), or Southern Qi, 479 - 502). The 晉 Jin rulers had been driven from north to south by northern tribes.

4.

Nanjing theme performance

5.

Nanjing qin school?

6.

Nanjing and qin songs (see also The qin in popular culture)

7.

Matteo Ricci in Nanjing

I do not know whether Ricci ever wrote down comments comparing Nanjing and Beijing.

8.

Tentative Nanjing associations

9.

Gao Longbo

10.

金陵吊古 Jinling Diao Gu (In Nanjing Mourning the Olden Days; 9 sections)

The original preface begins:

The original lyrics (in nine titled sections) begin:

11.

牡丹賦 Mudan Fu (Rhapsody on Peonies; 1 section)

The original introduction is as follows,

The original lyrics are 14 lines of 7 + 7 :

No translation yet.

12.

Yang Biaozheng and Nanjing

Handbook of qin master Huang Longshan, from Jiangxi but living in Nanjing (see image and QSCB, Chapter 7); the preface was written in Nanjing.

Apparently printed in Nanjing by

Yang Jiasen.

Handbook of Li Ren; tentative association with Nanjing based on its connection to Taiyin Buyi and Taiyin Chuanxi, below.

Handbook of Xiao Luan; association with Nanjing, tentative and perhaps peripheral, largely based on comments by Xu Jian linked above.

Second handbook of Xiao Luan; association with Nanjing also tentative.

Handbook of the famous Nanjing qin master Yang Biaozheng (see

image and QSCB,

Chapter 7); he apparently created or adapted all of the melodies, at least two of them directly connected to Nanjing (see below).

Zangchunwu is a district of Nanjing; published by eunuchs (compare

Yuwu Qinpu).

Compiled by Yang Lun of Nanjing (see image and QSCB, Chapter 7)

Compiled by Zhang Tingyu, perhaps of Nanjing

All three sung versions were published in Nanjing handbooks (1585, 1589 and 1618). The melody has long been associated with Ruan Ji; a famous Nanjing brick relief shows him as one of the Seven Sages.

This melody, published first in Nanjing, later appears in Japanese handbooks, showing a qin connection between Nanjing and Japan dating from Shin-Etsu (Jiang Jingshou).

Note the Matteo Ricci connection and the comment about a player named Gao Longbo.9

First surviving version is 金陵鄭養居校傳 Revised by Zheng Yangju of Jinling (Nanjing) and transmitted (not reconstructed)

The qin player Xiao Sihua is said to have played this here by a clear stream in Purple Mountain

(details).

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

This website is focused mainly on qin music as published during the Ming dynasty. Relevant historical sources in English for this period include:

(Return)

A program on the theme of Nanjing could also be expanded to include surrounding areas, such as 滁州 Chuzhou, about 100 km northwest of Nanjing, location of Ouyang Xiu's

Old Toper's Pavilion

(see Zui Weng Yin).

(Return)

The above image is discussed under

Shishang Liu Quan.

(Return)

To my knowledge no research has been done in this area. It is a very complex topic, and it should include analysis of how melodies published earlier and changed when published in Nanjing handbooks. I play many of these earlier versions of the melodies, but have not studied the versions published in Nanjing carefully enough to be able to discern any trends.

(Return)

A Jinling Qin Society (金陵琴社 Jinling Qinshe) was established in Nanjing in 1934 (Jinling is an old name for Nanjing), and today there is some discussion of an historical Jinling Qin School (金陵琴派 Jinling Qin Pai), or simply Jinling School (金陵派 Jinling Pai). Perhaps a program could be constructed of versions of melodies claiming such a connection. For example Wuzhizhai Qinpu (1722) has three melodies said to be Jinling School versions:

Yi Qiao Jin Lü, Ou Lu Wang Ji, and Qiu Sai Yin (three further are listed as 金派 Jin Pai; I am not sure if this is the same). There is also

Huaigu Yin from

1884. However, I am not familiar with a usable description of the characteristics of such a school, which in any case presumably changed over time.

(Return)

One can read of the flowering of Chinese songs and opera in Nanjing during the late Ming dynasty, but to my knowledge no detailed study has been done of Nanjing's importance to the development of qin songs.

(Return)

Ricci's impression of Nanjing can be seen in the following quote from Matteo Ricci, China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583-1610 (as translated by Gallagher; see also Jun Fang, p.5):

(Return)

Much of comment here on associations with Nanjing is tentative simply because when looking in original Ming dynasty sources I sometimes cannot distinguish clearly whether references are to Beijing or Nanjing. An example is in the expression "capital city" (京師 jingshi), which apparently could refer to Nanjing even after around 1421 even after the official main capital was moved to Beijing; for the rest of the dynasty Nanjing remained a secondary capital city with parallel administrations.

(Return)

Apparently living in Nanjing at the time of Matteo Ricci: note the possible connection with Mozi Bei Ge.

(Return)

In ToC;

Guide 25/212/386 lists this title only in 1585 (QQJC IV/311). The preface says that the melody commemorates

Yang Biaozheng's returning to Nanjing with 張徵軒 Zhang Zhixuan (Zhengxuan?) during Mid-Autumn Festival of 1579, playing the qin and intoning beneath the moon.

Translation incomplete (see

jpg of full text and section titles).

疏鑿秦淮斷地脈,埋金豫鎮鍾山中....

(Return)

In Toc;

Guide 26/214/396 lists a Mudan Fu only in 1585 (QQJC IV/344). The introduction recalls in spring 1575 friends going together to the 都察院 Chief Censorate to see peonies. (The Chief Censorate had moved from Nanjing to Beijing around 1425 CE, so presumably this was the location of the original Ming censorate, in Nanjing. The poem, line 12, refers to the 烏臺 Wutai, another name for the 御史臺 Yushitai, i.e, censorate.) With them was a censor, 白嶽何其賢 He Qixian from Baiyue (in Anhui; bio/1091xxx). The introduction also mentions 沈萬三家 the home of Shen Wansan (bio/1158; Yuan/Ming), a man of great wealth who had built a mansion in Nanjing at the beginning of the Ming dynasty.

In spring of 1575, the third month, friends together walked around the (former?) Chief Censorate looking at peonies. The stems were dark green and the buds had just opened - more than 110 of them. It was truly glorious in its appeal. As we climbed to the courtyard pavilion, look up at the wall worry about the poem (?). The censor He Qixian from Baiyue commented....

當階旗旎見名花,含態含嬌如欲語。

秣陵自昔比洛陽,平章宅裏春未央。 ("秣陵 Moling [i.e., Nanjing] compares itself to Luoyang?")

祇今庭中堆繡谷,染就玄湖山水鄉。

丹延有種不足持,檀心倒暈眾未知。

輕盈自合湘娥姿,濃艷爭誇六一詞。

遲日酐來難自持,低昂向背競瑤姿。

露容長信初妝罷,風態昭陽乍舞時。

攢__披蕤動曉寒,餘芬凝弄鬱金團。

(__ = 手+族 12886 xuan = 旋、繁、手挑物、長引)

豪奢莫論千金價,愛護真如百寶蘭。

欲問花神歲月賒,托根曾向石崇家。

可憐金谷當年麗,

添得烏臺此日華。 (金谷 Jin Gu was west of Luoyang.)

繁華一去不可復,捧日堯心今尚在。

一年一度一對花,當盃莫惜花蘋酹。

(Return)

Another possibility is Yu Xian Yin, which refers to Yang Biaozheng. None of these three has, to my knowledge, yet been reconstructed. In fact, very few melodies with extensive lyrics have been reconstructed. As of 2016 I have done several of my own reconstructions, as listed

here. I do not feel that such reconstructions are complete until I can play them from memory and, in the case of qin songs, sing them, or find someone who can sing them, in a manner that seems appropriate to the lyrics.

(Return)

Return to the Guqin ToC