|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| ZCZZ in the ToC / Birds | 五線譜 transcription 首頁 |

|

Wild Geese on the Frontier

Zhi mode: here 2 3 5 6 7 2 3 2 |

塞上鴻

1

Saishang Hong A wild goose soars 3 |

The preface to the earliest surviving publication of this melody, in 1589, says that the melody was created as a lament on the barbarian border regions, adding that this makes the theme comparable to that of the melody Yellow Clouds of Autumn at the Frontier.4

The preface then describes a border scene, bleak everywhere, eyes filled with dust and haze, winds chilling the bones. Above this in the blue firmament wild geese soar, calling out "liao li" and thus evoking the phrase, "The king's business never ends, (so) I do not have the leisure to return home." It then seems to say that the misery surrounding this is so deep that only a military sage playing an ancient qin can alleviate it.

The preface to the earliest surviving publication of this melody, in 1589, says that the melody was created as a lament on the barbarian border regions, adding that this makes the theme comparable to that of the melody Yellow Clouds of Autumn at the Frontier.4

The preface then describes a border scene, bleak everywhere, eyes filled with dust and haze, winds chilling the bones. Above this in the blue firmament wild geese soar, calling out "liao li" and thus evoking the phrase, "The king's business never ends, (so) I do not have the leisure to return home." It then seems to say that the misery surrounding this is so deep that only a military sage playing an ancient qin can alleviate it.

This 1589 preface, reprinted in 1609, was repeated in a number of later editions (either verbatim or in paraphrase) even when the music is quite different. Versions of the music itself survive in at least 32 more handbooks from 1647 to 1914;5 of these at least 12 have commentary.6

At least one later handbook is more specific about the person in the border regions, saying the melody was created by Su Wu,7 (ca. 140 - 60 BC) a Han ambassador famously detained by the Xiongnu; while forced to work as a shepherd in the desert he is said to have sent a message home by tying it to the foot of a goose. Although this attribution is certainly not historically correct, it is interesting for the image it conjures up.

Some of the later handbooks also comment on the melody itself, which is quite remarkable for its modality, including many non-pentatonic notes (see note count chart) and even some chromatic passages.8 These characteristics, the chromaticism in particular, may well be related to the borderland theme. However, it creates many problems of interpretation, as the positions of many of the potentially non-pentatonic notes are written with some ambiguity.9 It should be pointed out here that these ambiguously written notes are mostly notes that seem often to characterize zhi mode melodies of this period.10

There may be some uncertainty about the relative pitch names to assign to these notes (see below), but the present discussion is based on considering the relative tuning of the qin to be 2 3 5 6 7 2 3, putting the melody into a la - mi mode: the scale it seems to follow is 6 1 2 3 5 (relative pitches) with "7" not uncommon, and the "1" often sharped.11 (Note that Yellow Clouds of Autumn at the Frontier is also a la - mi mode melody.)

With the transcription based on a tuning considered as 2 3 5 6 7 2 3 it can easily be seen that it is the note 1 or 1 sharp that is most often written unclearly, and my inability to find patterns or consistency in the usage often makes it difficult to remember whether a note in such a passage should be 1 or 1 sharp. If there are modal rules for this then perhaps by playing the notes precisely as written one might learn and internalize these. However, it is also possible that these altered notes are there simply to provide unexpected colors; in this case performers might justifiably feel free to make their own decisions about when to play 1 or 1 sharp, based on their own mood at the time.

Note, however, that later versions of this melody seem to have become somewhat less modally adventurous (see for example the second handbook, dated 1647).

Also complicating reconstruction are some seemingly awkward fingerings,12 some apparently conflicting instructions,13 and some instructions that are simply uncertain or unclear.14

The melody also has some repeated note patterns that, in addition to the tonality, characterize its structure. Some of these have been noted in my transcription.15

Although Saishang Hong eventually became a very popular melody, surviving as mentioned in 33 handbooks to 1914, the next editions after the 1589 original (not counting the 1609 reprint) did not appear until 164716 and then

1670 (the latter had two versions17). The 1647 version and the first one in 1670 are both quite different from the 1589 tablature, but the second version dated 1670 (further comment) is very similar to that of 1589. The fourth handbook is Chengjiantang Qinpu, published in 1689;18 from here until 1914 the melody appears quite regularly, apparently with quite a bit of variety.

At present there seem to have been two reconstructions (published?) of Saishang Hong:

My own reconstruction from 1589 is written out in staff notation but not yet recorded.21

The source of this melody is not at all clear. At the front of the earliest tablature, for the 1589 edition, is the statement "Revised by Zheng Yangju of Jinling (Nanjing) and transmitted".22 This suggests the melody was already in the active repertoire at that time. Then the 1609 edition changes "transmitted" to four smaller characters that mean "transmitted from Korea".23 This rather dramatic statement does not seem to be repeated elsewhere.

In contrast, the editor of Lü Hua (1833) writes that Saishang Hong sounds like northern Kunqu.24 He mentions the claim of an association with Korea, but thinks this was probably added for its exotic appeal, and perhaps also to disguise the fact that it was actually in a style of Kunqu, one associated with a particular opera writer.25

1.

Saishang Hong 塞上鴻 (Sai Shang Hong; VII/169)

It is thought that this melody was written as a lament on the barbarian border regions. Comparable to Yellow Clouds of Autumn at the Frontier, extending for thousands of miles, haze and dust as far as the eye can see, the west wind biting into the bones, the scenery extremely desolate. Look at the wild geese, soaring in the sky, calling out "liaoli" over the landscape of the Purple Fortress (the Great Wall in desert regions). These liao li sounds are exceedingly mournful, expressing, "The king's business never ends, (so) we do not have the leisure to return home." The feelings are gut-wrenching; listeners burst into tears. The melody is pathetic, its color so hurtful. In order for sounds to dispel the homesickness and worries of home from a group of soldiers, then someone like the (military sages with) white eyebrows (must play) on true strings (such as those on the qin) of Emperor Yu Shun. People of like minds must listen to this attentively.

(Translation tentative; see summary.)

Melody (see

transcription)

14 Sections; no subtitles or lyrics

27

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

The Chinese does not specify number, so the title could also be translated as "Wild Goose on the Frontier", or "Wild Frontier Goose". This would be particularly appropriate if the thought is of a goose taking a message home.

2/1184 塞鴻 saihong says the messenger story was inspired by that of Su Wu on the frontier (see Han Jie Cao, and note that 1893 attributes the melody to Su Wu);

References: 周德清﹕長江萬里白如練,淮山數點青如澱。江帆幾片疾如箭,山泉千尺飛如電。

晚云都變露,新月初學扇,塞鴻一字來如線。

plus 白居易﹕晚秋夜﹕碧空溶溶月華靜,月里愁人吊孤影。花開殘菊傍疏籬叶,葉下衰桐落寒井。

塞鴻飛急覺秋盡,鄰雞鳴遲知夜永。 凝情不語空所思,風吹白露衣裳冷.。

and 贈江客詩﹕江柳影寒新雨地,塞鴻聲急欲霜天。愁君獨向沙頭宿,水繞蘆花月滿船。芦花月满船。

(Return)

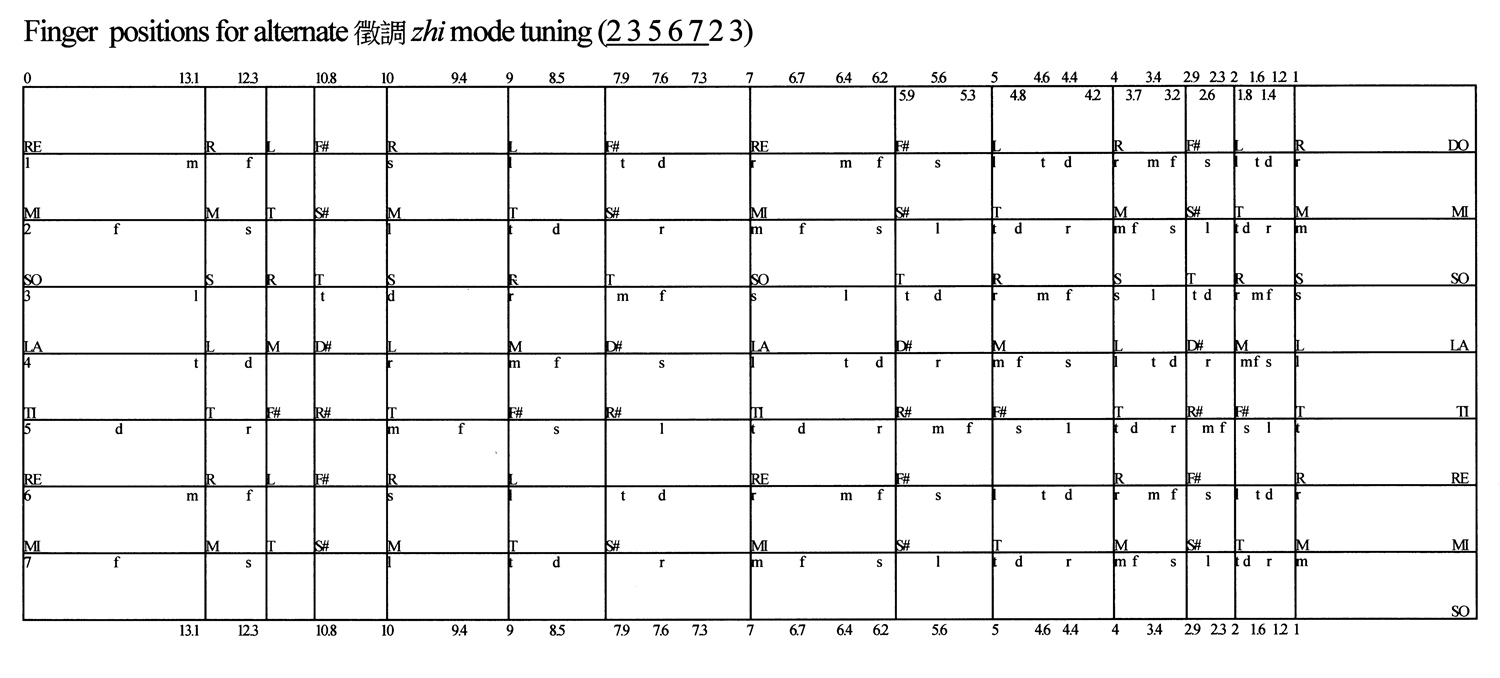

| 2. Zhi mode (徵音 zhi yin, elsewhere called 徵調 zhi diao) | Finger positions for Saishang Hong (expand) |

According to my understanding of modal usage in the Ming dynasty, the reason Saishang Hong was said to be in zhi mode (徵音 zhi yin) was that the tonal center is on the equivalent of the open fourth string, called the "zhi string". However, this is not a typical zhi mode melody.

According to my understanding of modal usage in the Ming dynasty, the reason Saishang Hong was said to be in zhi mode (徵音 zhi yin) was that the tonal center is on the equivalent of the open fourth string, called the "zhi string". However, this is not a typical zhi mode melody.

Almost all Ming dynasty qin melodies seem to be either do-sol modes or la-mi modes (comment) and in the present melody the open zhi string, to my understaning, should in fact be considered as la (6), making this a la-mi mode melody. However, for this to be the case the tuning, which is here the same as standard tuning, must be considered as 2 3 5 6 7 1 2. For typical zhi mode characteristics see Shenpin Zhi Yi (including the la - mi considerations) and also Modality in early Ming qin tablature.

In short, the selection of which relative pitch in any particular melody should be considered as "la" (or for that matter "do", 1) is not always immediately clear. Some might make claims about this based on cosmological arguments (related to charts like this and on essays such as this one taken from here), or even based on an understanding of modal theory, but the best test is to play the melody for traditional musicians who can sing solfeggio and see what they sing as do (more comment). By this standard, in Shen Qi Mi Pu the zhi mode tuning generally seems best considered as 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 ; elsewhere sometimes 4 5 7b 1 2 4 5 seems appropriate. However, what seems to work best here is 2 3 5 6 7 2 3.

This tuning, 2 3 5 6 7 2 3, is very unusual: no tuning on the chart here has an open string considered as ti (7) - or for that matter none is without a string tuned to do. How did that happen here? Is it related to the fact that, as the chart below shows, there seems to be an ambiguity as to whether this note should be 1 or 1 sharp (transcribed as C or C#)? In fact, this melody seems clearly to be in a la-mi mode, and it is not uncommon in the early qin repertoire for la-mi mode melodies to have this ambiguity. Again see comments under Shenpin Wuyi Yi.

Note, finally, that this melody could almost be played with the fifth string tuned up a half a pitch (i.e., the same as ruibin tuning, commonly used for la-mi melodies); the harmonic coda would have to be changed but otherwise there is only one note in the whole piece that is played on the open fifth string.

| \ Pitch

Section \ |

A | B♭ | B | C | C♯ | D | D♯ | E | F | F♯ | G | G♯ | Total |

| 1 | 34 | 2 | 7(+1B#) | 8 | 14 | 18 | 1 | 7 | 93 | ||||

| 2 (harm.) | 11 | 1 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 34 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 15 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 63 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 2 | 11 | 7 | 17 | 17 | 3 | 4 | 81 | ||||

| 5 | 24 | 5 | 16 | 9 | 16 | 20 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 102 | |||

| 6 | 34 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 19 | 1 | 29 | 2 | 12 | 118 | |||

| 7 | 18 | 6 | 10 | 20 | 18 | 13 | 85 | ||||||

| Sub-totals | 161 | 22 | 53 | 39 | 98 | 2 | 121 | 1 | 10 | 56 | 3 | 576 |

Although this is only the data from 7 of the 14 sections, from it one can see that 489 of the 576 notes fall into a basic scale of A C D E G (i.e., 6 1 2 3 5); this becomes 528 of the 576 if you include the 30 C#s. Looking at it another way, the musical mode is mostly a "minor pentatonic" version of the standard scale A minor scale (i.e., a "la-mi mode"), but not infrequently (i.e., when C becomes C#) switching to the "major" pentatonic version (further analysis). In some cases the use of C vs C# jumps back and forth; in other cases one of the two dominates for a while. Note here that Sections 2 and 7 are mostly pentatonic: Section 2 is purely in harmonics, and Section 7 is pentatonic except for the 6 occurrences of B. La-mi melodies often include this "ti" (here "B") as a sort of upper tone for la (here A).

As for the non-pentatonic notes in addition to B and C#, these in general usually occur on or with slides, with the two most common non-pentatonic notes not surprisingly connected to the two most common pentatonic notes (A and E): B (the note to be "avoided") is, as just mentioned, usually connected to A, while F sharp (F# / 4#) is usually connected to E.

As for notes that are stressed, all 14 sections end on A except the third (E) and the closing coda (A and E together). Beyond this almost all punctuated phrases end on either A or E, next most common being the occasional D then, towards the end, an even more occasional C.

In the past there does not seem ever to have been modal analysis based on note counts or phrase endings, or even based on identifying significant notes. However, there does seem to have been an early awareness of the exceptional nature of the modality here. This can be seen in some of the early comments about the melody avoiding the open fifth string ("B"); it also avoids harmonic notes equivalent to it though, as the chart above shows, the note "B" does at times occur as a stopped note.

The first such comment seems to have been the brief note under the title with the first tablature of

1670, where at front it says "忌散五絃", which can be translated either as "Avoids the open 5th string" (showing awareness of this fact), or "Avoid the open 5th string", which would be a command for the player to do so. Then at the end of Section 2 it expands on this by stating that, although the equivalent of this note is clearly indicated in the preceding harmonic passage, that note really shouldn't be there. It adds, however, that since the tablature was "楊師較遍 an edition revised by Master Yang", a lowly disciple such as the present writer could not change it. In fact, there are several places later in the piece where in the 1589 version this note does appear, but which in 1670 version 1 it seems always to be raised half a pitch, giving a strange effect even for this piece.

Although the 1589 version also generally avoids this note (B in my transcription - not part of the pentatonic scale), it is there clearly in the opening (once) and closing (four times) harmonic passages and is specifically indicated in a few other places (in particular on the 5th position of the 7th string - changed to 4.8 in 1670/#1). In other places it is generally a passing tone and sometimes might be interpreted as a different note. The implications of all this are discussed further above; see also the note count below.

3.

Illustration

4.

Comparison with Yellow Clouds of Autumn at the Frontier

5.

Tracing Saishang Hong (also see

tracing chart below)

Zha's Guide does not include

Bei Saishang Hong or Nan Saishang Hong, related melodies found only in 1760. The second version of 1670 seems largely to copy 1589; the others seem all to have substantial melodic and modal differences. The prefaces mostly repeat that of 1589, with the most detailed musical commentary in 1833 (see below).

6.

Prefaces and afterwords to Saishang Hong

7.

Su Wu theme

8.

Chromatic passages in Saishang Hong

Note that all of these are descending note passages and most of them include both the natural and flatted third above the tonal centers A (i.e., la) and C (i.e., do).

9.

Ambiguous notes

10.

Problems with ambiguously written notes in zhi mode melodies

12.

Awkward fingering

13.

Conflicting instructions (measure references are to my transcription)

14.

Uncertain instructions (measure references are to my transcription)

Could some of the inconsistencies be indications that there were multiple copyists for this tablature, or that the present tablature was copied/modified from quite an earlier version?

15.

Structures (measure references are to my my transcription)

Other sequences include the ones beginning at:

16.

Second handbook: 徽言秘旨 Huiyan Mizhi (1647)

17.

Third handbook: two versions of 1670

The two 1670 versions are very different from each other, with the latter one resembling very closely the 1589 version (including the 三退 three step chromatic slide that dramatically appears near the beginning of the 1589 edition).

18.

Fourth handbook: Chengjiantang Qinpu (1689)

19.

Recording of 塞上鴻 Sai Shang Hong by 吳景略

Wu Jinglue

20.

Recording by Hammond Yong (容克智 Yong Hak-chi)

21.

22.

Zheng Yangju 鄭養居

23.

1609 Preface: Korean connection?

24.

Commentary in 律話 Lü Hua (1833) concerning Saishang Hong

(XXI/446), Korea, and Kun melodies (Wikipedia:

Kunqu)

魏良輔 Wei Liangfu (1501-84; Bio/2575; ICTCL/514) "played an important part in the development" of Kunqu, writing a work called 曲律 Rules for Kunqu Tunes. According to ICTCL, pp.514/5, Wei "played an important part in the development" of Kunqu. Though "not a composer in the modern Western sense", he blended different regional forms to create an opera style that quickly became very popular, including with the literati, and also wrote several important treatises including 曲律 Rules for Kunqu Tunes."

Zha Fuxi (Guide [197] 155) says that the Saishang Hong in Lü Hua uses 無射羽 wuyi yu mode (adding that it has an attached explanation of the tuning method), has 10 sections, 律呂名 the names of notes next to the tablature, and 後附釋文 has commentary afterwards. Since Lü Hua was not reprinted until the 2010 edition of Qinqu Jicheng (XXI/446), I have not yet had time to assess just how closely this version is related to the 1589 version, which has 13 sections and is categorized as using zhi mode. However, based on the following comments, it is clear that this 1833 Saishang Hong still uses standard tuning. And based on the comments above it seems likely that the melody is said to be in a yu mode because it is centered on la - mi; wuyi (which elsewhere suggests a different tuning) perhaps here suggests which note should be considered as do.

On the other hand, that same year (1833) a version of Saishang Hong was also published in Erxiang Qinpu, which was reprinted in facsimile before its inclusion in QQJC (XXIII/163). The mode for this version is called "羽音 yu yin" and it is also in 10 sections, so perhaps it is very similar to the one in Lü Hua (though it does not have the note names). At first glance the first four sections seem roughly similar to 1589, with the same tonal centers but fewer non-pentatonic notes; from the fifth section the melody seems quite different.

The Erxiang Qinpu commentary mentions 腔調 qiangdiao, a term used for mode or melody in opera, perhaps also suggesting a connection to Kunqu. Its entire preface is as follows (tentative translation):

Note that, of the clusters that indicate multiple stroke finger techniques described above, 1589 has one, a changsuo. Regarding 閆晴峰 Yan Qingfeng, 晴峰 Qingfeng is a nickname and 閆 is 閻, but I can find only a 闕嵐號晴峰 42373.44 Que Lan nickname Qingfeng, a painter. I have not found a reference to 36 pitches or sounds. The significance of mentioning multiple stroke clusters could be that such clusters have an influence on how a qin melody is paired with a vocal melody if one puts them together according to the traditional pairing method of one right hand stroke for each character (one cluster for a character would be very different).

The Lü Hua commentary is particularly interesting for its comments on Kunqu, in particular mentioning one of the persons often said to have been one of its founders, Wei Liangfu (魏良輔, 1501-84; see

above).

It is against this background that the melody Saishang Hong emerges (see comment on its source). Although I have not yet found the name "Saishang Hong" in any Kunqu context, it does not seem impossible that a qin melody that was created or evolved in the latter part of the 16th century might in some way follow a Kunqu style. The specific connection made in 1833 seems on the face of it quite fantastic: since the melody had changed quite a bit by 1833, and in any case there is virtually nothing known about the earliest Kunqu melodies, it would be very difficult to find specific connections. Nevertheless, the point seems important enough that one should try to do some research in this area.

The 1833 article seems to suggest that qin players would not wish to admit this connection, perhaps because opera was a part of popular culture, so they made up the connection with Korea. The article then makes some comparisons between the actual qin melody and Kunqu melodies. In this regard it should be noted that Kunqiang (Kun style singing) puts many notes on each syllable while qin songs generally have one note for each syllable (ornaments occasionally add more). However, because Saishang Hong never had lyrics, any connection can only be seen through the melody.

The Lü Hua afterword, as quoted in Zha Fuxi's Guide (Guide [477] 233) is incomplete (see XXI/451-3). The Guide indicates omitted parts by ........, and puts into smaller type text which in the original has two lines per column. The following text was originally just quoted from the Guide, but since then most of the missing text has been put back in.

塞上鴻一曲,楊掄載於伯牙心法篇內。其序云,"按斯曲,蓋傷戎邊而作也。彼《黃雲秋塞》千里蕭條,極目煙塵,西風砭骨,景物凄涼,於斯極矣。顧瞻鴻鴈,翱翔於青霄之上,嘹嚦於紫塞之鄉,聲嚦嚦而語哀哀。王事靡鹽,不遑歸處。感懷者,倍為斷腸聞之者,涕淚交頤。是曲聲律慘悽,音韻悲傷,寫出一段征人懷鄉憂國之意,真虞絃中之白眉者也。同志者細聽察焉。

No further information about Zheng, but perhaps this means he wrote the following note (in double columns, smaller print):

After this the full size print continues with three "疑竇 yidou" (matters of enquiry), each in a separate section, as follows.

琴家(按?)自六徽至九徽為中部。九徽至十三徽外為下部。一徽至六徽為上部。上部如字韻中之上聲。下部如字韻中之去聲。中部如字韻中之平聲。惟入聲無定位三部中縮上一徽皆為入聖。元周德清作中原音韻所以祗取平上去三聲而以入聲分居三韻,此填北曲者之所宗,今此操自入促彈,上部八段九段,皆用大指掐用中指(用大、中指掐撮?);此正是上平入三聲之法。惟出促十徽,方用食指,此其疑竇二也。

琴家分段如從中部起音中部音盡之後將入末部必有搯撮三聲為亂。上部、下部皆如之。或潑剌、搯撮而繁音必雙彈潑剌。大曲必有繁音接連幾撮是也。此操第一段末一撮收林羽至十段中一撮收林羽尾聲末一撮收角羽上中下三部皆不用搯撮、潑剌。

中部無繁音、無雙聲,此正是昆腔家用笙笛合絃索之法。蓋滚拂、撥刺撥刺、雙彈伏,笙笛中無此音,在琴家最有關係,而此操一概不用,此其疑竇三也。

(This, the third matter for enquiry, mentioned such qin techniques as 掐撮 qiacuo (usually 掐撮三聲 qiacuo sansheng), 滾輔 gunfu, 潑剌 pola and 雙彈 shuangtan, all quite common but which I cannot find here in Saishang Hong. It also mentioned instruments from Kunqiang.)

Although this lengthy commentary makes comparisons between qin techniques and the Kun melody style, it seems that the Lü Hua tablature (as with the 1589 Saishang Hong tablature discussed above) avoids the mentioned clusters that indicate multiple stroke fingering techniques such as 搯撮 taocuo (perhaps there is one 長鎖 changsuo).

This whole section is puzzling.

25.

See the previous footnote as well as the commentary under opera.

26.

Original Preface

The phrase "王事靡鹽,不遑歸處。" is a variant of lines found in at least three entries in the 詩經 Book of Songs:

As here they all begin (Waley), "The king's business never ends, (so) I have no time to ...."

As for "真虞絃中之白眉者" see 33531.119 虞絃 and 23191.430 白眉.

27.

Music

(Return)

Image from the internet

(section of 2nd image on page) - appropriate classical illustration not found yet. Here and in other literary references, although the skies may be grey along the horizon, overhead they can be blue. Here the goose flying in the 青霄 blue firmament perhaps reminds the observer of home not just because the geese can fly there but because the skies at home are also blue.

(Return)

Although there is no apparent melodic connection between these two melodies, both seem to have characteristics of a la - mi mode. (Most early guqin melodies seem either to have do as their primary tonal center and sol as their secondary tonal center [do - sol mode] or la as their primary tonal center and mi as the secondary tonal center [la - mi mode]. It is interesting to compare these modes with the Western major and minor modes.)

(Return)

Zha Guide 29/232/--; none of the handbooks has lyrics or section titles. The earliest surviving version is the one in the 1589 edition of

Boya Xinfa, part of

Zhenchuan Zhengzong Qinpu. In 1609 the general title of the handbook was changed to Qinpu Hebi; here Saishang Hong is the first melody in the second folio of Boya Xinfa.

(Return)

The attached is a pdf file with all this original commentary as copied out in Zha Fuxi's Guide, pp. 232-4.

(Return)

There seems to be only handbook making this connection to Su Wu,

Kumu Chan Qinpu (1893). However, in addition to the preface below, see also the footnote

above, which suggests that "sai hong" can also evoke the image of a bird carrying a message home from the frontier, thus indirectly evoking the Su Wu story.

(Return)

The first chromatic passage, very near the beginning of Section 1, actually exceeds normal chromaticism with notes I can only transcribe as "C♯- C♮- B♯- C♮". A tentative list of these chromatic passages is as follows

(measure references are to my transcription):

(Return)

The tablature here does not use the modern decimal system of writing finger positions, which dates only from the end of the Ming dynasty, and because Saishang Hong has many non-pentatonic notes clearly indicated, care must be used when trying to interpret notes which may be ambiguous. Potential ambiguities in the earlier system are discussed in some detail elsewhere on this site (see, e.g., Determining the notes). As discussed there and

elsewhere, if the old system is used carefully, as apparently it was in Shen Qi Mi Pu, there need be no more ambiguity in the old system than in the new. However, the present handbook is not as precisely written as Shen Qi Mi Pu. Thus, for example, at least in Saishang Hong it never distingushes between 7.3 (old system 七下) and 7.6 (七八) (expand the chart

linked above), writing only 七半 (7 and a half). This, compounded with there being numerous non-pentatonic notes clearly indicated, makes it often very difficult to clarify the ambiguities.

(Return)

For more on the ambiguously written notes see Shenpin Zhi Yi. The discussion here uses note names based on considering zhi mode tuning as

2 3 5 6 7 2 3 (see comment). Thus, as an example of difficulties caused by ambiguously written notes, the tablature may indicate that a passage should ascend using 1 sharp then descend using 1 natural; an otherwise apparently similar passage might indicate just the reverse. Without knowing the logic of the difference between these two passages, it is difficult to remember how to play them. Or the tablature might indicate a two step slide (二上) from 6 to 2 without specifically indicating the intermediate step; the inconsistency of usage elsewhere might make it difficult to decide whether the intermediate note should be 7, 1 or 1 sharp.

(Return)

Standard tuning for the qin is usually considered either as 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 or 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 (1 = do). However, neither of these can allow the melody to be following in the standard Chinese pentatonic scale: 1 2 3 5 6. The melody can only be considered as having this relative sacle if the relative tuning is considered as 2 3 5 6 7 2 3 (D E G a b d e in my transcription). For more on this see the comment above.

(Return)

An example of what I mean here by awkward fingering is a passage that requires the left hand to go up and down on one string when it would be easier to play the melody on two or three strings. Generally I assume the creator of the passage is looking for a special effect, but this is not always certain.

(Return)

The most common of these is the use of "𠂊" written above a stroke. Generally this is an abbreviation of "急" ji, which should mean "quickly". However, sometimes the word 爰 yuan (in tablature usually short for 緩 huan, meaning slow) is also attached, there is an ornament added to the note, or the note comes at the end of a phrase. All of these would seem to preclude playing the note quickly. See also the first two notes of Section 2, where the clusters indicate two quick harmonic notes followed by the direction "省", i.e. "少息", to "pause". This seems to suggest either that "𠂊" has another meaning nowhere defined, or that (perhaps because it is so short and easy to write) it is not uncommonly written unintentially. Regarding a meaning nowhere defined, the most logical would be that it indicates cutting off the sound quickly, i.e., creating a staccato effect. However, this effect would be so dramatic (and generally awkward to accomplish) that it would be very surprising for there to be no related comment or explanation anywhere.

(Return)

Similarly, there can be confusion from the use of what seem to be redundant, idiosyncratic and/or archaic figures in the tablature. For example,

(Return)

The most distinctive patterns are the variations on a rising and falling note sequence first occuring in Section 1 (mm.25-26) but then more clearly established in Section 2 (mm. 72-4) and later found in Section 4 (mm. 84-6 and again 115-7), Section 6 (mm. 163-6 and again 172-5), Section 9 (mm. 297-9), Section 11 (mm. 375-8), Section 12 (mm. 407-9) and Section 14 (mm. 444-6).

m.166, comparable to those at mm.288, 411 and 431.

m.126 and m.137

mm.300-3 and mm.447-9

Many of these are related to rhythm, so they continue to emerge as I work to complete my reconstruction.

(Return)

This version, which has no commentary, has 15 sections with no subtitles. An examination of the first three sections shows the melody following the outlines of the 1589 version, but with many of the notes changed, particularly ones that are not pentatonic.

(Return)

The two versions in the 1670 handbook 琴苑新傳全編 Qinyuan Xinchuan Quanbian (1670) can be found in QQJC XI/383 and XI/497.

(Return)

This version, reprinted in QQJC XIV/276, uses the new decimal system to indicate finger positions. It has 14 untitled sections, no commentary. The opening multiple note cluster is different but after this it is clearly related to the previous editions, though quite different.

(Return)

Statements can be found on the internet suggesting that Wu Jinglue reconstructed (and recorded in 1980?) this melody, but as of 2021 I have not yet seen/heard it. It is not included here or on his

double CD, and it is not transcribed in The Qin Music Repertoire of the Wu Family.

(Return)

Hammond's lineage is outlined under

Qing Rui. His recording is very recognizable when compared to the earliest surviving version, at the same time showing that many of the non-pentatonic pitches had been changed.

(Return)

Could there also have been one by

Zhan Chengqiu

(comment here)?

(Return)

The 1589 edition has no further information other than that Zheng was from 金陵 Jinling (Nanjing); the actual inscription is "金陵鄭養居校傳".

(Return)

The edition of Yang Lun Taigu Yiyin published in 1609 adds to

the above the comment "傳自朝鮮 transmitted from Korea". In 1592 豊臣秀吉 Toyotomi Hideyoshi (see in Wikipedia) had sent Japanese troops into Korea as the beginning of an avowed attempt to conquer China. Chinese troops were then sent to Korea. Many remained stationed there during a truce that lasted until 1597, when the Japanese renewed the attack. More Chinese troops were sent, and casualties were high. The war ended after Hideyoshi's death in 1598. The fact that there is no mention of Korea in the 1589 edition suggests this statement may have been added here simply because Korea was the most important frontier region at the time; in line with this the statement might better be translated as "transmitted by a soldier on the Korean border". See also the further comment on this in the following footnotes.

(Return)

This commentary by the compiler, 戴長庚 Dai Changgeng (XXI/451-453) is not yet translated, but it mentions a number of important people and terms, including:

朝鮮 Korea (first mentioned together with Zheng, then at 451下左1行)

昆腔 Kun melodies (first mentioned at 451下左7行)

沈寵綏 Shen Chongsui (452下右2行, an early opera expert)

魏良輔 Wei Liangfu (first mentioned also at 452下右2行; a founder of Kunqu?)

樂緯 Yue Wei (first mentioned at 453下右5行; Han dynasty Divination of Music?).

"此曲別開生面。長鎖、滾拂、撥刺、搯撮三聲等指法皆不用。用律謹嚴取音,明淨三十六音皆。閆晴峰云「宏音亮節高唱入雲」此八字形容腔調如聞三十六聲。

This melody breaks new ground. It does not use such

clusters (multiple stroke finger techniques) as changsuo, gunfu, boci and tao cuo san sheng. In using the notes one (must) precisely bring out the tones, making bright and clear the 36 pitches. Yan Qingfeng said, 'Grand sounds clear beats high singing enters clouds': these eight words describe a qiangdiao that is like listening to 36 sounds."

下注云:金陵鄭養居校傳自朝鮮。

"Lü Hua: The melody Saishang Hong was written down by Yang Lun in Boya Xinfa. Its preface says, It is thought that this melody was written as a lament on the barbarian border regions ........."

At the end of this section is a comment saying, "Revised by Zheng Yangju of Jinling and transmitted from Korea."

(no translation yet)

Concerns details of each of the 10 sections of the melody. Ends "....It has the stylistic rules and layout of Kun melodies (my emphasis); this is the first matter for enquiry."

Qin players consider the area from the 6th to the ninth huia to be the center part; 9th to 13th is the lower part; 1st to 6th the upper part. (去聲,平聲,入聲 determined by which part???)....This was the second matter for enquiry.

(Return)

(Return)

The original preface from 1589 is as follows:

按斯曲,蓋傷戎邊而作也。彼黃雲秋塞,千里肅條,極目煙塵,西風砭骨;景物淒涼,于斯極矣。顧瞻鴻鴈,翱翔于青霄之上。嘹嚦于紫塞之鄉;聲嘹嚦而語哀哀,「王事靡鹽,不遑歸處」。感懷者,倍為腸斷;聞之者,涕淚交頤。是曲聲律慘悽,音韻悲傷,為出一段征人懷鄉憂國之音,真虞絃中之白眉者也。同志者細聽察焉。

#162: "王事靡鹽,不遑啟處。", "王事靡鹽,不遑將父。", and "王事靡鹽,不遑將母。";

#167: "王事靡鹽,不遑啟處。".

(Return)

My reconstruction is still tentative and not yet recorded.

(Return)

Return to the top

Appendix: Chart Tracing 塞上鴻 Saishang Hong

Based mainly on Zha Fuxi's Guide,

29/232/--; none of the handbooks has lyrics or section titles (further comments above)

|

琴譜

(year; QQJC Vol/page) |

Further information

(QQJC = 琴曲集成 Qinqu Jicheng; QF = 琴府 Qin Fu) |

|

01 真傳正宗琴譜

(1589; VII/169) |

14+1 sections; zhi mode; the version covered here, reprinted 1609

Some of it unique modal characteristics are mentioned here; compare next. |

|

02. 徽言秘旨

(1647; X/175) |

15; zhi, but mode seems less adventurous

|

|

02.a 徽言秘旨訂

(1692; fac/???) |

Copy of previous

|

|

03.a 琴苑新傳全編

(1670; XI/391) |

14; zhi diao; "忌散五絃 avoid the open 5th string"

(comment)

|

|

03.b 琴苑新傳全編

(1670; XI/505) |

14+1; zhi diao; "濟南王猶龍校譜 tablature corrected by Wang Youlong of Jinan"

"周本 Zhou volume"; seems mostly to follow 1589, with many of the non-pentatonic notes |

|

04. 澄鑒堂琴譜

(1689; XIV/282) |

14+1; zhi yin

|

|

05. 蓼懷堂琴譜

(1702; XIII/261) |

12+1; zhi yin

|

|

06. 誠一堂琴譜

(1705; XIII/373) |

14; zhi yin

|

|

07. 五知齋琴譜

(1722; XIV/499) |

16+1; zhi yin; preface mostly repeats 1589, the author adding he obtained it in 1669 from the Chunyi Hall (Chunyi Zhai: 純一齋. 27915.1 Chunyi: nickname for 金淑 Jin Shu and 杜立德 Du Lide), but it was in very bad condition; after considerable study he made his own version. The afterword comments on the melody itself (recording?). |

|

08. 存古堂琴譜

(1726; XV/263) |

16+1; zhi yin

|

|

09. 琴書千古

(1738; XV/418) |

16+1; zhi yin

|

|

10. 春草堂琴譜

(1744; XVIII/284) |

10; yu yin but "即用中呂中呂均彈 play with zhonglü jun"

Still related |

|

11. 琴劍合譜

(1749; XVIII/326) |

13; zhi yin

|

|

12. 穎陽琴譜

(1751; XVI/99) |

14+1; zhi yin;

|

|

13a. 蘭田館琴譜

(1755; XVI/244) |

12; zhi yin; 北塞上鴻

Bei Saishang Hong, a related melody found only here

(Afterword; see also next) |

|

13b. 蘭田館琴譜

(1760; XVI/247) |

13; zhi yin; 南塞上鴻

Nan Saishang Hong; a related melody found only here

(Afterword; see also previous) |

|

14. 琴香堂琴譜

(1760; XVII/82) |

10+1; zhi yin

|

|

15. 研露樓琴譜

(1766; XVI/471) |

16+1; zhi yin; "即霜鴻引,明妃作 same as Shuanghong Yin by Ming Fei" (Wang Zhaojun); preface mentions Huangyun Qiu Sai |

|

16. 自遠堂琴譜

(1802; XVII/417) |

16+1; shang yin

still related; seems to begin with a double stop |

|

17. 裛露軒琴譜

(>1802; XIX/295) |

16+1; zhi yin

"光裕堂譜 Guangyu Hall tablature" |

|

18. 琴譜諧聲

(1820; XX/197) |

10; 變徴調 bianzhi diao (standard tuning)

|

|

19. 峰抱樓琴譜

(1825; XX/336) |

10; yu yin

|

|

20. 鄰鶴齋琴譜

(1830; XXI/55) |

10; mode not indicated; still related

|

|

21. 二香琴譜

(1833; XXIII/163) |

10+1; yu yin; afterword comments on the tablature

|

|

22. 律話

(1833; XXI/446) |

10+1; 無射羽 wuyi yu; writes in note names; still related;

most detailed commentary (q.v.) including commentary with each section and an afterword that mentions the 1589 version |

|

23. 悟雪山房琴譜

(1836; XXII/417) |

11; 無射均, 羽音, 用中呂均彈 "but don't tighten 5th string". This handbook is connected to the Lingnan school; its tablature here is for music quite similar to that in the recording by Hammond Yung, but see also 1870 |

|

24. 張鞠田琴譜

(1844; XXIII/326) |

16+1; zhi diao, yu yin;

begins with double stop |

|

25. 稚雲琴譜

(1849; XXIII/361) |

10+1; yu yin

|

|

26. 蕉庵琴譜

(1868; XXVI/67) |

16; shang yin; also "無射均, 羽音, 用中呂均彈, 不緊五絃 (don't tighten 5th string)"

commentary |

|

27. 琴瑟合譜

(1870; XXVI/179) |

10; mode note indicated (also in 琴府 Qin Fu); tablature for se paired with qin;

Hammond Yong's YouTube recording is from here but without the se |

|

28. 以六正五之齋琴xue秘書

(1875; XXVI/242) |

16+1; zhi yin; begins with double stop; commentary compares to Huangyun Qiu Sai

|

|

29. 天聞閣琴譜

(1876; XXV/438) |

10+1; yu yin, shang diao ("= 1849")

|

|

30. 響雪齋琴譜

(1876; ???) |

Originally part of 1807?

cannot find, but Zha Guide p.(221) 179 says 13 sections, zhi yin |

|

31. 希韶閣琴譜

(1878; XXVI/368) |

10; 變徴 bianzhi (standard tuning)

compare 1820 |

|

32. 枯木禪琴譜

(1893; XXVIII/85) |

16; 變徴音 bianzhi yin (standard tuning)

"漢蘇武所作 by Su Wu" |

|

33. 詩夢齋琴譜

(1914) |

not indexed and not in Qinqu Jicheng

|

Return to the Zhenchuan Zhengzong Qinpu intro,

to the annotated handbook list

or to the Guqin ToC.