|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Qin Bios | 首頁 |

|

Su Shi

1

|

蘇軾

Su Dongpo with a lady musician (pipa) 2 |

Su Shi (1037 - 1101), better known as 蘇東坡 Su Dongpo, was one of the most influential poets and essayists during the northern Song dyansty (960–1127). His brother Su Che was also a poet.3 There is some discussion of Su Dongpo's connections to the qin in Xu Jian's Introductory History of the Qin, 6a2.

Su Shi (1037 - 1101), better known as 蘇東坡 Su Dongpo, was one of the most influential poets and essayists during the northern Song dyansty (960–1127). His brother Su Che was also a poet.3 There is some discussion of Su Dongpo's connections to the qin in Xu Jian's Introductory History of the Qin, 6a2.

The work Miscellaneous Accounts of Qin Matters, a collection of writings about the qin usually attributed to Su Shi but sometimes to Su Zhe, was included in Folio 100 of the 14th century encyclopaedia called Shuo Fu (Persuasion of the Suburbs). This volume still exists.4

Poems by Su Shi directly mention qin at least 61 times.5 Qinshu Daquan (QQJC Vol. V) includes at least 22 such poems and essays he wrote concerning qin. These poems and essays include (original texts are in a footnote below):6

Folio 17, #56 (V. 384; 1 writing, including 1 poem)

Folio 17, #57 (V. 384; 1 letter)

Folio 18, #55 (V. 403; inscription [with comments])

Folio 19A, #31 (V. 418; [from an essay {repeated} that has 1 poem])

Folio 19A, #33 (V. 419; 1 poem)

Folio 19B, #91 - #93 (V. 431; 3 poems)

Folio 19B, #161 (V. 441; 1 poem)

Folio 20A, #53 - #55 (V. 447; 3 poems)

Folio 20B, #56 - #58 (V. 455/6; 3 poems)

Qinshu Daquan also has stories by other people that mention Su Dongpo and qin, sometimes quoting him. For example, see (original text below):7

Folio 17, #39 (mentions him with 武崇穆 Wu Chongmu; V. 380)

Why in its case will the strings not sing?

If you say sound in the fingers lies,

Why from your fingers do we hear no ring?

Some handbooks say he wrote the melody He Wu Dongtian. And his lyrics set to qin melodies (by others) include the following,

Should this also include the melody Xiangsi Qu (Gu Qin Yin)?10 Introductions to it suggest he created it, or at least the lyrics, though it does not seem to be part of his canonical work. The various introductions all concern Su Dongpo and a female ghost who played the qin. In the version translated by Van Gulik,11 Su Dongpo hears someone playing a sad song outside his window. When he goes to look he sees a young woman, who immediately disappears. In the morning when digging in that area he finds an old qin.

It may also be appropriate to mention Su Dongpo's Three Songs on Yangguan Lyrics. This and related comments by Su himself may be of relevance in tracing the source of the melody used today with Yangguan Sandie, but as yet I have not carefully analyzed this.12

Su Dongpo is said to have created a list of "16 Enjoyable Activities, the final one of which mentioned "playing qin for an understanding listener".14

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Su Shi 蘇軾 (蘇東坡 Su Dongpo, sometimes written Su Dongbo)

33250.234 眉山人,洵子,轍兄,字子瞻 from Meishan, son of Su Xun, brother of Su Che, style name Zizhan. Sources (see also

Wiki) include:

Michael A. Fuller, The Road to East Slope, The Development of Shu Shi's Poetic Voice

Burton Watson, Selected Poems of Su Tung-p'o

Xu Yuanzhong, Su Dong-po - A New Translation

Lin Yutang, The Gay Genius, The Life and Times of Su Tungpo

The references quoted here come from various poetry collections and The Collected Writings of Su Dongpo (東坡文集 Dongpo Wenji).

(Return)

| 2. Su Dongpo with a lady musician (pipa) | Japanese image: Su Dongpo with qin? |

The image above is part of 仇英,東坡寒夜賦詩圖 a long scroll by

Qiu Ying (款) called Dongpo on a cold evening writes poetry. The woman with the pipa is said to be a female entertainer (or Skilled Woman). The full scroll is

here. There are many online copies but I haven't found where the original is kept.

The image above is part of 仇英,東坡寒夜賦詩圖 a long scroll by

Qiu Ying (款) called Dongpo on a cold evening writes poetry. The woman with the pipa is said to be a female entertainer (or Skilled Woman). The full scroll is

here. There are many online copies but I haven't found where the original is kept.

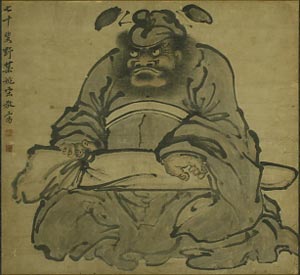

Compare the image at right, from a standing screen, copied from a Japanese web page. The image seems clearly to be of 鍾馗 Zhong Kui, but the text there says (in part),

古裂會 骨董品古美術品専門オークション Bone (?) valuable object and old beautiful object

寶曆元年 (1751: Houreki 1st year).... 僧泉寺(極書)天保元年(1830: Tenpo 1st year)

長泉寺 裏鐘馗抱琴畫(紙本 ヤケ シミ スレ)

The last line says "Chosenji Temple, Drawing of Zhong Kui embracing a qin". On the left side of the screen the writing says: 七十叟野某姚宋敬 .

Is it saying that Su Dongpo was the painter? Otherwise I do not understand this inscription, or the relationship between Su Dongpo, the Eight Immortals, the inscription and the image, which is clearly Zhong Kui

(Wiki), who was not one of the 8 Immortals.

(Return)

3.

Su Zhe 蘇轍 (1039 - 1112)

Su Zhe, style name 子由

Ziyou, though overshadowed by his older brother Su Shi, was one of the "Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song". (Indiana Companion, p.727)

(Return)

4.

Miscellaneous Accounts of Qin Matters (雜書琴事,十三則 Zashu Qinshi, 13 entries; 一卷 one folio)

See Xu Jian, Qin Shi Chu Bian 蘇軾

(English). Qinshu Cunmu entry 103 (4 lines) attributes the work to Su Shi and refers to the version in Folio 100 of 說郛本 Shuo Fu, where it is the fifth entry, but it gives no other details. However, not all of this is generally accepted as the work of Su Shi. There has also been debate suggesting some or all of it should be attributed to Su Shi's brother Su Zhe. Plus there is also evidence that the two sometimes worked on things together. In sum, today the consensus seems to be that at least parts was more likely to have been written by Su Shi himself but disagreement as to what.

Although there are 13 essays in the Shuo Fu edition, later versions trimmed this down to 10, omitting what are here #6, #7 and #13. The 13 Section version is as follows:

- 家藏雷琴

余家有琴,其面皆作蛇腹紋,其上池銘云:「開元十年造,雅州靈關村。」其下池銘雲:「雷家記八日合。」不曉其「八日合」為何等語也?其嶽不容指,而弦不先攵,此最琴之妙,而雷琴獨然。求其法不可得,乃破其所藏雷琴求之。琴聲出於兩池間,其背微隆,若薤葉然,聲欲出而隘,徘回不去,乃有餘韻,此最不傳之妙。

A Family Heirloom: Our Lei Family Qin

My family owns a qin with snake-belly crack patterns on its surface. An inscription near the upper sound hole: "Made in the 10th year of Kaiyuan (722 AD), Lingguan Village, Yazhou." Near the lower sound hole is carved: "The Lei Family records: Eighth day, assembly." I do not understand what "eighth day assembly" signifies. The bridge (yue) is so narrow it barely fits a finger, yet the strings do not buzz—this is the most exquisite feature of this qin, unique to Lei family instruments. Failing to uncover their method, I dismantled our treasured Lei qin to study it. The sound seems to emerge from between the two sound holes; the (inner?) back is slightly arched like a shallot leaf. The tone, seeking to escape yet confined, lingers and resonates — the beauty of this is the one least likely to be transmitted.

(Compare this description here ("from pool to pond...."; explained); modern commentators say this shows Su Shi was talking about what later was called the nayin.) - 歐陽公論琴詩

「昵昵兒女語,恩怨相爾汝。劃然變軒昂,勇士赴敵場。」此退之《聽穎師琴》詩也。歐陽文忠公嘗問仆:「琴詩何者最佳?」余以此答之。公言此詩固奇麗,然自是聽琵琶詩,非琴詩。余退而作《聽杭僧惟賢琴》詩雲:「大弦春溫和且平,小弦廉折亮以清。平生未識宮與角,但聞牛鳴盎中雉登木。門前剝啄誰扣門,山僧未閑君勿嗔。歸家且覓千斛水,凈洗從前箏笛耳。」詩成欲寄公,而公薨,至今以為恨。

Ouyang Xiu’s Intonation of Listening to a Qin begins,

"Affectionately whispering a young boy and girl speak, in fondness or anger they (call) each other 'dear'.

Abruptly it changes to the heroic, brave warriors charging to the battle field."

These are actually lines from Han Yu’s "Listening to Monk Ying Play the Qin." Once, Ouyang Xiu asked me: "Which poem about the qin stands supreme?" I cited this one. He replied: "Though brilliant, this describes the pipa, not the qin.""

Later, I wrote, "Listening to Monk Wei Xian of Hangzhou Play the Qin":

"Warm and gentle, the great string sighs; / The small string is crisp as ice — clear, pure, and bright.

Though I know not gong or jue modes, I hear oxen low in jars, and pheasants cry mid-flight..."

Before I could send it to him, Ouyang passed away. To this day, I regret it. - 琴非雅聲

世以琴為雅聲,過矣。琴正古之鄭、衛耳。今世所謂鄭、衛者,乃皆胡部,非復中華之聲。自天寶中坐立部與胡部合,自爾莫能辨者。或雲,今琵琶中有獨彈,往往有中華鄭、衛之聲,然亦莫能辨也。

Qin Is Not ‘Elegant Music’

People call the qin "elegant music" — this is mistaken. The qin is precisely the ancient music of Zheng and Wei (generally deemed ‘vulgar’). What we now call Zheng-Wei tunes are actually melodies of the (nomadic) Hu, no longer truly Chinese. Since the Tianbao era (742–756), when court music and Hu music merged, none have been able to distinguish them apart. Some say modern pipa solos often contain Chinese Zheng-Wei tones — yet none can truly tell.- 琴貴桐孫

凡木,本實而末虛,惟桐反之。試取小枝削,皆堅實如蠟,而其本皆中虛空。故世所以貴孫枝者,貴其實也,實,故絲中有木聲。

Qins Value Young Tong Wood

Most trees are solid at the core but hollow at the tips. Only the tong tree (often equated with paulownia) is the opposite. Cut a young branch — it’s as solid as wax, while the trunk is hollow. Thus, we value "sunzhi" (young branches) for their density. Dense wood makes the silk strings resonate with a woody timbre.- 戴安道不及阮千里

阮千里善彈琴,人聞其能,多往求聽。不問貴賤長幼,皆為彈之,神氣衝和,不知何人所在。內兄潘岳每命鼓琴,終日達夜無忤色,識者嘆其恬淡,不可榮辱。戴安道亦善鼓琴,武陵王晞使人召之。安道對使者破琴曰:“戴安道不為王門伶人。”余以謂安道之介,不如千里之達。

Dai Andao Falls Short of Ruan Qianli (Ruan Zhan)

Ruan Qianli excelled at the qin. Hearing of his skill, people flocked to listen. Regardless of status or age, he played for all — serene, as if no one were there. His brother-in-law Pan Yue often asked him to play all night; Ruan never showed annoyance. Scholars admired his detachment from fame or disgrace. When Dai Andao, also a master, was summoned by Prince Wu Ling Xi, Dai smashed his qin before the messenger: "Dai Andao is no entertainer for princes!" I say Dai’s pride paled before Ruan’s enlightenment.- 琴鶴之禍

衛懿公好鶴,以亡其國,房次律好琴,得罪至死。乃知燒煮之士,亦自有理。

Obsessing about Qin and Cranes

The obsession Duke Yi of Wei (r. 668-660) had with with cranes cost him his kingdom (when it was invaded by the 狄 Di); the love Fang Cilü (房琯 Fang Guan; 697-763) had for the qin led to his execution. Thus, even refined passions can bring ruin.- 天陰絃慢

或對一貴人彈琴者,天陰聲不發。貴人怪之,曰:「豈絃慢故?」或對曰:「弦也不慢。」

Slack Strings on Cloudy Days

A man played qin for a noble on an overcast day, but the sound was faint. The noble asked: "Are the strings slack?" The player replied: "The strings are not slack." (n.b., humid weather can make silk strings sound dull).- 書《醉翁操》後

二水同器,有不相入,二琴同手,有不相應。今沈君信手彈琴,而與泉合,居士縱筆作詩,而與琴會。此必有真同者矣。本覺法真禪師,沈君之子也,故書以寄之。願師宴坐靜室,自以為琴,而以學者為琴工,有能不謀而同三令無際者,願師取之。元祐七年四月二十四日。

Postscript to "The Old Toper's Melody" (Zui Weng Cao)

"Two waters in one vessel may not blend;

Two qin in one hand will not harmonize."

Yet when Master Shen plays the qin freely, his notes merge with mountain springs; When the recluse [Ouyang Xiu] writes poetry unrestrained, his verses fuse with the qin. This reveals a profound unity. The Chan Master Benjue Fazhen is Master Shen’s son, so I write this for him. May the Master sit peacefully in his quiet chamber, becoming a qin himself, while treating his students as qin-makers. If any achieve perfect resonance without deliberate effort, may the Master embrace them.

Written on the 24th day of the 4th month, Yuanyou 7 (1092 CE).- 書林道人論琴、棋

元祐五年十二月一日,游小靈隱,聽林道人論琴棋,極通妙理。余雖不通此二技,然以理度之,知其言之信也。杜子美論畫雲:「更覺良工心獨苦。」用意之妙,有舉世莫之知者。此其所以為獨苦歟?

Notes on Monk Lin’s Discourse about Qin and (the board game) Weiqi

On the 1st day of the 12th month, Yuanyou 5 (1090 CE), I wandered to Little Lingyin Temple and heard Daoist Monk Lin discourse on qin and weiqi. His understanding penetrated their deepest mysteries. Though unskilled in both arts, I sensed the truth of his words. Du Fu once wrote of painting:

"All the more I feel the master artisan’s heart labors alone."

The subtlety of artistic intention often eludes the world — this is why it is a "lonely labor."- 書仲殊琴夢

元祐六年三月十八日五鼓,船泊吳江,夢長老仲殊彈一琴,十三弦頗壞損而有異聲。余問雲:「琴何為十三絃?」殊不答,但誦詩曰:

「度數形名豈偶然,破琴今有十三絃。

此生若遇邢和璞,方信秦箏是響泉。」

夢中瞭然諭其意,覺而識之。今晚到蘇州,殊或見過,即以示之。寫至此,筆未絕,而殊老叩舷來見,驚嘆不已,遂以贈之。時去州五里。- Zhongshu (釋仲殊 the Monk Zhongshu, birth name 張揮 Zhang Hui) was a well-known poet praised by Su Shi; Recording Zhongshu’s Qin Dream

about 125 of his poems survive but the only one that mentions qin is the one here about a 13 string qin.

At the fifth watch [3–5 AM] on the 18th day of the 3rd month, Yuanyou 6 (1091 CE), our boat moored at Wu River. I dreamed of the elder monk Zhongshu playing a qin with thirteen strings — partially damaged yet producing unearthly sounds. I asked:

"Why thirteen strings?"

Zhongshu did not answer but chanted:

"Measure, form, and name — no accident! This broken qin now bears thirteen strands.

Only meeting Xing Hepu in this present life, Will prove the qin zither is a ‘Singing Spring.’"

In the dream, I understood. Upon waking, I wrote it down. Reaching Suzhou that evening, I showed it to Zhongshu. As I wrote these words, my brush still in hand, the old monk knocked on the boat’s side. Astonished, he sighed endlessly — so I gave it to him.

Written five li from the city.- 書王進叔所蓄琴

知琴者以謂前一指後一紙為妙,以蛇蚹紋為古。進叔所蓄琴,前幾不容指,而後劣容紙,然終無雜聲,可謂妙矣。蛇蚹紋已漸出,後日當益增,但吾輩及見其斑斑焉,則亦可謂難老者也。元符二年十月二十三日,與孫叔靜皆云。

On the Qin Collected by Wang Jinshu

Connoisseurs deem a qin exquisite if the distance before the bridge barely fits a finger and behind it barely holds paper, while snake-belly grain marks its antiquity. Master Wang Jinshu’s treasured qin fits this: the front scarcely admits a finger, the rear barely holds paper—yet it produces no discordant sounds. Its snake-belly grain has begun emerging; with time, it will deepen. That we witness its dappled patterns now suggests this qin defies aging.

23rd day of the 10th month, Yuanfu 2 (1099 CE). Discussed with Sun Shujing.- 文與可琴銘

文與可家有古琴,予為之銘曰:

「攫之幽然,如水赴谷。

醳之蕭然,如葉脫木。

按之噫然,應指而長言者似君。

置之枵然,遺形而不言者似僕。」

與可好作楚詞,故有「長言似君」之句。「醳」、「釋」同。鄒忌論琴雲:「攫之深,醳之愉。」此言為指法之妙爾。

Inscription for a qin belonging to Wen Yuke (Wen Tong)

Wen Yuke owned an ancient qin. I wrote this inscription for it:

"Pluck darkly—like water rushing valleys;

Release coldly — like leaves leaving trees.

Pressed, it sighs — as you, my lord, speak at length;

Resting hollow — as I, your servant, keep silence."

Yuke loved writing Chu ci-type poetry, hence the line "speak at length like you."

Note: 醳 (release) = 釋 (release). Zou Ji once said of the qin: "Pluck deeply; release joyfully" — speaking of fingering’s artistry.

23rd day of the 6th month, Yuanfeng 4 (1081 CE).- 元豐四年六月二十三日,陳季常處士自岐亭來訪予,攜精筆佳紙妙墨求予書。會客有善琴者,求予所蓄寶琴彈之,故所書皆琴事。

(Colophon) 1081/6/23 CE

The recluse Chen Jichang (陳慥 Chen Zao; Bio/1353; Giles) came from Qiting to visit me, bringing fine brushes, excellent paper, and sublime ink to request my calligraphy. A guest skilled in qin happened to be present and asked to play my treasured instrument. Thus, all I wrote here concerns the qin. - 琴貴桐孫

Some of these passages are quoted again below.

(Return)

5.

Qin mentioned in Su Shi's poetry 61 times

See Stuart H. Sargent, Music in the World of Su Shi (1037-1101): Termiology, Journal of Sung-Yuan Studies 32, pp. 46 (2002; online). Pages 46-51 has a comprehensive account of Su Dongpo's comments on qin; see also pp. 54-5. Sargent is mentioned again

below.

(Return)

6.

Su Shi qin-related poems and essays in

Qinshu Daquan

There are at least 22 such items in that 1590 compendium, as follows:

Subtitles: 桐貴孫枝、安道介不如千里達、琴偈燒煮琴鶴、伯倫淵明非達

- Concerns Tang dynasty qin player 張華 Zhang Hua of Hangzhou (not the writer Zhang Hua)

尚書郎張華字子野,杭州人,善戲有風味,見杭妓有彈琴者,忽撫掌曰: 異哉,此箏不見許時,乃爾黑瘦耶。 世以琴為雅聲,過矣。正古之鄭、衛耳。今世所謂鄭、衛者,乃皆胡部,非復中華之聲,自天寶中,坐立部與胡部合,自爾莫能辨者。 或云琵琶中有獨彈,往往有中華鄭、衛之余聲,然亦莫能辨。 凡木本實而末虛,惟桐反之,試取小枝削,皆堅實如蠟,而本皆中虛。故世所以貴孫枝者,其實也,實故絲中有木聲。

Secretarial Court Gentleman Zhang Hua, courtesy name Ziye, was a native of Hangzhou. He was skilled in humor and had a refined taste. Seeing a courtesan in Hangzhou playing qin, he suddenly clapped his hands and said: "How strange! This zheng, which I have not seen in a long time, has become so dark and thin!"The world considers the qin an elegant sound, but that is no longer true. It is, in fact, just like the ancient music of Zheng and Wei. And what is now called the music of Zheng and Wei is actually all foreign (Hu) music and no longer the sound of China. Since the Tianbao era, when the sitting and standing ensembles merged with Hu ensembles, no one has been able to distinguish them. Some say that (today's?)pipa solo pieces, occasionally show remnants of our country's Zheng and Wei music. Even so, no one can truly discern them." Yet even these can no longer be clearly recognized. All trees are solid at their core and hollow at the tips — only tong wood (the paulownia) is the opposite. If you take a small branch and shave it, you will find it entirely firm, as if made of wax, yet the trunk itself is hollow inside. Thus, the reason why the world values "grandson branches" (young branches of the paulownia tree) is their true solidity. Because of this solidity, silk strings produce a wooden resonance when plucked."

- Concerns the qin player 阮千里 Ruan Qianli (i.e., Ruan Ji's grand-nephew 阮瞻 Ruan Zhan)

阮千里善彈琴,人聞其能,多往求聽,不問貴賤長幼皆為彈之,神氣衝和,不知向人所在。內兄潘岳每命鼓琴終日,達夜無忤色。識者嘆其恬澹,不可榮辱。戴安道亦善鼓琴,武陵王遣使人召之,對使者破琴曰:安道不為王門伶人。余以為安道之介不如千里之達。 - 蛇蚹文 Snake-scale cracks on a qin (33717.95/2: same as 蛇腹紋, see above and below; a type of duanwen)

知琴者以謂前一指後一紙為妙,以蛇腹文為古。晉叔所舊琴前幾不容指,後劣容紙,終無殺聲可為妙矣。蛇腹文已漸出,後日當益增。但吾輩及見其班班焉,則亦可謂難老者也。武昌主簿吳亮君採攜其故人沈君土琴之說與高齋先生之銘空同子之文文太平之頌以示余,余不識沈君而讀其書,反覆其義趣,如見其人,如聞土琴之聲。余昔從高齋先生游,常見其寶一琴,無名無識不知其何代物也,請以告二子使從先生求觀之,此土琴者,待是琴而後和。 - About 荅沈疏書 A Letter Responding to Shen Shu (? Bio/xxx)

答沈竦書:軾再啓土琴當與響泉韻磬並為當代之寶,而鏗金瑟瑟遂蒙輟惠拜賜間赧汗不已,不敢逆來意,謹當傳示子孫,永以為好也。然軾素不解彈,適會峨眉紀老枉道,見過令其侍者快作數曲,拂歷鏗然,真如若之言也,戲以一偈問之:若言弦上有琴聲,放在匣中何不鳴,若言聲在指頭上,只合於君指上聽。錄呈以發千里一笑也。寄示佳紙筆名舛重煩厚意一一拜領訖,感作不可言,適有少冗書不周謹。 - Duke Yi of Wei 衛懿公 (ca. 660 BCE; Bio/51) and his love of cranes

衛懿公好鶴以亡其國,房次律好琴得罪至死,乃知燒煮之士亦自有理,或對一貴人彈琴者天陰聲不發,貴人怪之曰:豈弦慢故耶?對曰:弦也不慢,琴弦舊則聲喑,以桑葉揩之輒復如新,但無如其青何耳。 - An old qin in the home and a visit in 1081 from 陳季常 Chen Jichang (陳慥 Chen Zao; Bio/1353; Giles)

文與可家有古琴,予為之銘,攫之幽然,如水赴谷,釋之蕭然,如葉脫木,按之噫然,應指而長言者,似君之句釋,釋同鄒忌論琴雲,攫之深釋之愉,此言為指法之妙。元豐四年六月二十三日,陳季常處士自岐亭來訪予,攜以嘉紙妙墨求予書,會客有善琴者,予所蓄寶琴彈之,故所書皆琴事。 - This paragraph has no subdivisions but seems to have three topics:

(Criticism of 劉伯倫 Liu Bolun [劉伶 Liu Ling]) (The original text in Dongpo Wenji seems to have continued with story of 13-string qin: 元祐六年(1091)三月十八日五鼓.... but this is not included in QSDQ [see below])

劉伯倫常以鍤自隨,曰:「死即埋我。」蘇子曰:「伯倫非達者也,棺槨衣衾,不害為達。茍為不然,死則已矣,何必更埋!」

(Comment on Tao Yuanming for his stringless qin)

陶淵明作《無絃琴詩》,曰:「但得琴中趣,何勞絃上聲。」蘇子曰:「淵明非達者也,五音六律,不害為達,苟為不然,無琴可也,何獨絃乎!」

(Perhaps sometimes called《書林道人論琴棋》Daoist Lin discussing qin and chess)

元祐五年(1090)十二月一日遊小靈隱,聽林道人論琴棋,極有妙語(elsewhere:極通妙理)。予雖不通此二技,然以理度之,知其言之信也。杜子美論畫云:更覺良工心獨苦用意之妙,有舉世莫知之者,此其所以為獨苦歟。 - Duke Yi of Wei 衛懿公 (ca. 660 BCE; Bio/51) and his love of cranes

Folio 17, #56 (V. 384)

- 與彥正判官書 Yu Yan Zheng Pan'guan Shu: A Letter to Department Chief Yan Zheng (10209.15xxx; V.384)

古琴當與響泉韻磬,並為當世之寶,而鏗金瑟瑟,遂蒙輟惠,報賜之間,赧汗不已。又不敢遠逆來意,謹當傳示子孫,永以為好也。然某素不解彈,適紀老枉道見過,令其侍者快作數曲,拂歷鏗然,正如若人之語也。試以一偈問之:

「若言琴上有琴聲,放在匣中何不鳴?

若言聲在指頭上,何不於君指上聽?」

錄以奉呈,以發千裏一笑也。寄惠佳紙、名荈,重煩厚意,一一捧領訖,感怍不已。適有他冗,書不周謹。

(Poem is translated below)

Folio 17, #57 (V. 384)

- 聽賢師琴 Ting Xianshi Qin (V.384)

A letter, or part of a letter, by Dongpo, dated 1089 (see the end); it is quoted in part in the Qinshi Bu biography of Li Jingxian與次公同聽賢師琴。賢求詩,倉卒無以應之。次公言古人賦詩,皆歌所學,何必己云。次公因誦歐陽公贈李師詩,囑予書之以贈焉。元祐四年九月二十一日,東坡居士記。

Folio 18, #55 (V. 403)

- 銘文與可琴 Inscription for the Qin of Wen Yuke (V.403)

與可 Yuke, style name of 文同 Wen Tong (1018 - 1079; Bio/299; 13766.140)「攫之幽然,如水赴谷。

醳之蕭然,如葉脫木。

按之噫然,應指而長言者似君。

置之枵然,遺形而不言者似僕。」

- 破琴 Broken Qin

(Seems to be a continuation from the quote above from Dongpo Wenji:)

元祐六年三月十八日五鼓,蘇東坡船泊吳江,夢見方外交僧人長老仲殊彈一琴,十三絃,頗壞損,而有異聲,蘇東坡問:「琴為何十三弦?」仲殊默而不答,但誦一詩云:度數形名豈偶然,破琴今有十三絃。

此生若遇形和璞,方信秦箏是響泉。

Entry 31 from Folio 19 concerned the 3rd month, 18th day; for the 19th day see below

Folio 19A, #33 (V. 419)

- 破琴 Broken Qin

Introduction says, 序見雜錄即觀宋復古畫序㣲 (see below)破琴雖未修,中有琴意足。

誰為十三絃,音聲如佩玉。

新琴空高張,絲聲不附木。

宛然七絃箏,動與世相遂。

陋矣房次律,因循堕流俗。

懸知董庭蘭,不識無絃曲。

Folio 19B, #91 - #93 (V. 431-2; 3 poems),

- 聽武道士彈賀若 Listening to Daoist Wu Play Heruo (V.431)

37569.50#1 賀若:琴曲名(猗覺寮雑記)琴曲有賀若、最淡古。 東坡云,琴裏若能知賀若,詩中定合愛陶潛,以賀若比潛,必高人,或謂賀若弼殊陳不類,余考之蓋賀若夷也。夷善鼓琴,王涯居別墅, 常使鼓琴娛賓,見涯傳。東坡序。武道士彈琴云,賀若,宣宗 時待詔,不知何據,據序則知姓賀名若。

"Heruo": Name of a qin melody. (Yijueliao Zaji [edited by 朱翌 Zhu Yi?, 1097-1167]) says, Among qin pieces ones (10?) called "Heruo" are very subtle and ancient.

(Su) Dongpo said, Amongst qin pieces, people who can understand (the 10 nelodies by?) Heruo must also be able to understand the poetry of Tao Qian. To compare Heruo with (Tao) Qian one must have the judgment of a lofty man. Some say that (Heruo) refers to Heruo Bi of the Chen dynasty, but having investigated this I believe it is actually Heruo Yi. (Heruo) Yi was skilled at playing qin. When Wang Ya (this one d.835 CE?) stayed in his country villa he often had (Heruo) play qin to entertain guests - see the biography of (Wang) Ya. (Su) Dongpo's Preface says, The Daoist Wu, when playing qin said, "He Ruo". During the Xuanzong Emperor's time (r.712-756), he was a court msician - but what evidence is there? From the preface we learn his surname was He, given name Ruo.清風終日自開簾,涼月今宵肯掛檐。

琴裡若能知賀若,詩中定合愛陶潛。

A pure breeze keeps curtains open all day long,

Tonight will a cool moon agree to hang from the eaves? - 聽僧惟仙琴 Listening to a Qin of Monk Wei Xian (V.431)

See Sargent, p.52: Su writes that "he never could tell one note from another until he heard the monk Weixian 惟賢 play the qin, after which he must go home and wash out his ears, contaminated as they have been by the zheng and the transverse flute (di)."大絃春溫和且平,小絃廉折亮以清。

平生未識宮與角,但聞牛鳴盎中聲。

雉登木門前剝啄,誰叩門山僧未聞,君勿嗔。

歸家且覓千斛水,淨洗從來箏笛耳。 - 聽僧昭素琴 Listening to the Unadorned Qin

(su qin) of Monk Zhao (V.431/2)

至和無攫醳,至平無按抑。

不知微妙聲,究竟何從出。

散我不平氣,洗我不和心。

此心知有在,尚復此微吟。

Folio 19B, #161 (V. 441)

- 舟中聽大人彈琴 On a Boat Listening to a Great Man Play a Qin

彈琴江浦夜漏永,斂衽竊聽獨激昂。

風松瀑布已清絕,更愛玉珮聲琅璫。

自從鄭衛亂雅樂,古器殘缺世已忘。

千家寥落獨琴在,有如老僊不死閱興亡。

世人不容獨反古,強以新曲求鏗鏘。

微音淡弄忽變轉,數聲浮脆如笙簧。

無情枯木今尚爾,何況古意墮渺茫。

江空月出人响绝,夜阑更请弹「文王」。

Folio 20A, #53 - #55 (V. 447, 3 poems)

- 觀月彈琴 Observing the Moon and Playing Qin (V.447)

㣲露下眾草,碧空卷微雲。

月光為誰來,似為我與君。

水天浮四座,河漢落酒尊。

使我冰雪腸,不受麴糱醺。

尚恨琴有絃,出魚亂湖紋。 (Sargent, p. 48, translates lines 5-8)

哀琴本舊曲,妙耳非昔聞。

良時失俯仰,此見寧朝昏。

懸知一生中,道眼無由渾。- 西湖月下彈琴 On West Lake under a Moon Playing Qin (V.447)

謖謖松下風,藹藹壠上雲。

聊將竊比我,不堪持寄君。

半生寓軒冕,一笑當琴樽。

良辰飲文字,晤語無由醺。

我有鳳鳴枝,背作蛇蚹紋。

月明委靜照,心清缺奇聞。 (缺 is elsewhere 得)

當呼玉澗手。一洗羯鼓昏。

請歌南風曲,猶作虞書渾。- 次韻子由彈琴 Following a Rhyme Sequence of Ziyou and Playing Qin (V.447)

Ziyou was the style name of 蘇轍 Su Che, Su Shi's younger brother; translated in Sargent, p. 49琴上遺聲久不彈,琴中古意久長存。 (久 is elsewhere 本)

苦心欲記常迷舊,信指如歸自著痕。

意有仙人依樹聽,空教瘦鶴舞風寒。 (意 is elsewhere 應)

誰知千里溪堂夜,時引驚猿撼竹軒。 - 西湖月下彈琴 On West Lake under a Moon Playing Qin (V.447)

- 晦夫惠接䍦琴枕作此詩謝之 Huifu (Ouyang Bi) Bestows on me (?) a Cap and Qin Pillows; I Wrote this Poem to Thank Him (V.455)

攜兒過嶺今七年,晚途更著黎衣冠。

白頭穿林要藤帽,赤腳渡水須花縵。

不愁故人驚絕倒,但使俚俗相恬安。

見君合浦如夢寐,挽須握手俱ォ瀾。

妻縫接䍦霧縠細,兒送琴枕冰徽寒。

無弦且寄陶令意,倒載猶作山公看。

我懷汝陰六一老,眉宇秀發如春巒。

羽衣鶴氅古仙伯,岌岌兩柱扶霜紈。

至今畫像作此服,凜如退之加渥丹。

爾來前輩皆鬼錄,我亦帶脫巾欹寬。

作詩頗似六一語,往往亦帶梅公酸。 - 又 (i.e., same title as #56; V.455/6)

中郎不眠仰看屋,得此古椽圍尺竹。

輪囷濩落非笛材,破作袖琴徽軫足。 (破 is elsewhere 剖)

流傳幾處到淵明,臥枕綸巾酒新漉。

孤鸞別鵠誰復聞,鼻息齁齁自成曲。- 雪下琴 Qin under Snow (V.456)

寂寞王子猷,回舟剡溪路。 (舟 is elsewhere 船)

迢遙戴安道,雪夕誰與度。

倒披王恭氅,半掩袁安戶。

應調折弦琴,自和撚鬚句。 (琴弦 is elsewhere 弦琴; 鬚 is elsewhere 須) - 雪下琴 Qin under Snow (V.456)

(Return)

7.

Stories by others concerning Su Dongpo and qin

These two stories were included in Qinshu Daquan (1590),

Folio 17:

觀宋復古畫序 Preface to Looking at a Painting by Song Fugu (V.379)

Fugu was the style name of 宋迪 Song Di, a well-known painter from Luoyang; he painted a version of 瀟湘八景 Eight Scenes of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers. Under this general title are two subtitles:

- 東坡夢中琴詩 (Su) Dongpo has a dream about a qin poem

- 破琴詩見詠琴 Broken qin in a poem shows a melodious qin (?)

These interweave in a story that concerns a dream about a broken but melodious 13-string qin, so the second subtitle may simply refer to the included poem(s).

Of old it was said that during 713 - 42 Fang Guan, while serving as magistrate of Lushi during the Kaiyuan era (713–741), once passed through Xiakou Village with the Daoist mystic 邢和璞 Xing Hebo. They entered an abandoned Buddhist temple and sat beneath an ancient pine. Hebo ordered workers to dig a pond, where they unearthed a jar containing portraits of 婁師德 Lou Shide and 永禪師 Chan Master Yong. Smiling at Fang Guan, Hebo asked: "Does this feel familiar?" Suddenly, with piercing clarity, Fang Guan realized he had been Master Yong in a past life.

元祐六年三月十九日,余自杭還朝,宿吳松江,夢長老仲殊挾琴過予,彈之有異聲,熟視琴頗損,

而有十三弦。予嘆息不己。殊曰:「雖損尚可修。」曰:「柰十三絃何?」殊不答。

(Next,) on the 19th day of the 3rd month, Yuanruo 6 (1091), I returned to the capital from Hangzhou. Mooring at Wusong River, I dreamed that the elder monk 仲殊 Zhongshu approached me carrying a qin. As he played, strange sounds emerged. Looking closely, I saw the qin was not only damaged but also had thirteen strings.

I sighed in dismay. (But Zhong)shu said, "Though damaged, it can still be restored."

So I asked: "But what of these thirteen strings? He did not answer.

誦詩曰:

「度數形名豈偶然,破琴今有十三絃。

此生若遇邢和璞,方信秦箏是響泉。」

予夢中瞭然,識其所謂,既覺而忘之。明日晝臥,復夢珠來理前言,再誦其詩,方驚覺,而殊適至,意其非夢也。問之殊,蓋不知。

Instead, he chanted:

"Measure, form, and name — no accident, this broken qin now bears thirteen strands.

Only meeting Xing Hebo in this life, Will prove the qin zither is a ‘Singing Spring.’"

In the dream, I understood profoundly. Upon waking, the memory faded. The next day, as I napped, Zhongshu returned, recited the poem again, and vanished — whereupon I jolted awake. Uncannily, Zhongshu himself arrived just then, though he knew nothing of the dream.

是歲六月,見子玉之子子文於京師,求得其畫,乃作詩並書所夢其上。

That June in the capital, I met the son of Liu Ziyu, Liu Ziwen, and obtained a Tang-era painting [by Song Fugu of Lou Shide and Master Yong?]. So I composed a poem and recorded this dream upon it.

子玉名瑾,善作詩及行草書。 (Liu) Jin, styled Ziyu: master poet and calligrapher of cursive script.

復古名迪,畫山水草木蓋妙絕一時。 (Song) Fugu: landscape painter of unmatched skill.

仲殊本書生,棄家學佛,通脫無所著。 A scholar who renounced worldly life for Buddhism, embodying transcendent freedom.

皆奇士也。 All were extraordinary men.

(The original Dongpo Ji text then continues: 詩曰:

「破琴雖未修....Broken qin...., see

above).

Folio 17, #39 (V.380/1)

昭德樸齋錄 Zhaode Record of Puzhai

There is a 昭德文集 Zhaode Wenji by Zhao Gongwu (晁公武 14239.5: 12th c.), while 樸齋錄 Puzhai Lu is perhaps a work by 蒲瀛 Pu Ying called 蒲氏漫齋錄 Pushi Man Zhailu (32271.17 pushi: a type of fan), but I have not been able to find the connection between that and this text, which mentions Su Dongpo in connection with his friend 王晉卿 Wang Jinqing (王詵 Wang Shen Bio/108; Jin is written here with two 口 instead of two 厶) and two Daoist priests, 武崇穆 Wu Chongmu (Bio/xxx; 16623.xxx) and 費世隆 Fei Shilong (37565.xxx).

道士武崇穆善鼓琴,亦能攧竹騁。兹二伎頗結貴游然風貌不甚灑落。王晉卿賞其伎,與之往還。由此識蘇東坡。東坡因聽琴嘗以詩為贈。道士費世隆亦攻琴別無他業其不韻尤甚於武。武欲蔫之於二公令揮絃求詩共要虛譽。一日晉卿約東坡飯。上清宮時武、費與蔫飯起瀹(音藥)茗稍雍容間晉卿乃索琴求武、費各作一操。東坡據振衣索馬欲退。晉卿堅留聽琴。東坡曰:今日只求赴飯,意非聽琴。請俟他日,清集耳竟上馬去。翼日晉卿復見東坡,詰其所以。東坡謂晉卿曰:觀其人可以知其琴矣。何必更聽耶。

Daoist priest Wu Chongmu was a skilled qin player who was also fast at dianzhu (a game involving sketching bamboo?)....

There are probably also other references in Qinshu Daquan that I have not yet found.

(Return)

8.

Poem on the source of qin sounds (see above)

The translation is based on that of Xu Yuanzhong, Song of the Immortals, p.212. The original (see p.423) is:

若言聲在指頭上,何不於君指上聽?

Elsewhere the first phrase is written, "若言聲在琴絃上".

(Return)

9.

水調歌頭 Shui Diao Ge Tou

This is the name of a 95-character

cipai; the lyrics by Su Shi are the most famous ones in this form. The original and a translation are in

Wiki; they are included here under the

qin melody of this title.

As indicated by the preface to the poem, this was one of the poems written by Su Shi during Mid-Autumn (details).

Zha Guide 32/244/470 has six entries with this title, but two are duplicates, so there are actually four melodies for the three sets of lyrics; all lyrics fit into the same ci pattern. The six are as follows:

- Lixing Yuanya (1618; QQJC VIII/337)

The lyrics are those of Su Shi given just above; the melody is one of the handbook's 5 melodies for one-string qin. - Shu Huai Cao

(1677 [1]; XII/342)

"宮音"; "鐵篴老仙去,無復採花船...." - Shu Huai Cao

(1677 [2]; XII/363)

"徵音"; "君山已不作,獻曲久無人...." - Song Sheng Cao

(1682 [1]; XII/376)

Seems to be the same as 1677 #1 - Song Sheng Cao

(1682 [2]; XII/379)

Same lyrics as 1677 #2 but different music; mode is "商音" - Ziyuantang Qinpu

(1802; XVII/540)

Seems to be same as 1677 #1, but lyrics are paired instead of at end

None are yet reconstructed here.

(Return)

10.

Xiang Si Qu 相思曲

Also called 古琴吟 Gu Qin Yin. See details in the introduction to the 1585 version, including the

original lyrics.

(Return)

11.

Su Shi and the Ghost of Xiang Si Qu

Van Gulik translates this story in

Lore, pp.159-160 and there are further details here. Several other stories in that section of Lore also concern ghosts (and in one of his Judge Dee mysteries Van Gulik has a ghost appear to the judge as he plays qin in the middle of the night

[illustration]).

(Return)

12.

Su Shi and Yang Guan

See p. 70fn of Stuart Sargent, Music in the World of Su Shi as well as Sargent's "Colophons in Countermotion: Poems by Su Shih and Huang T’ing-chien on Paintings", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 52.1 (June 1992): 263–302. Sargent says the latter has "more on the Yang Pass song and its role as a theme in Song painting".

The 陽關詞 三首 Three Poems on Yangguan Lyrics (SSSJ 3:15.751) are:

- 贈張繼願

受降城下紫髯郎,戲馬臺南古戰場。

恨君不取契丹首,金甲牙旗歸故鄉。 - 答李公擇

濟南春好雪初晴,行到龍山馬足輕。

使君莫忘霅溪女,時作陽關腸斷聲。 - 中秋月

暮雲收盡溢清寒,銀漢無聲轉玉盤。

此生此夜不長好,明月明年何處看。

As can be seen, these have the same structure as the original Wang Wei poem, which was included in Yuefu Shiji, Folio 80.

Of these Sargent wrote,

With ci poetry, new lyrics were written following the pattern of an old melody long after the melody was lost. The poems here are 詩 shi rather than 詞 ci, and it is not clear whether they were applied to an actual surviving Tang melody, to a supposed Tang melody, or to a variety of melodies all with an appropriate structure. This also leaves out consideration of whether they were always paired, as in the qin examples, using one note for each character/syllable.

(Return)

14.

Su Shi's 十六樂事 16 Enjoyable Matters

Su Dongpo is said to have created a list of "16 Enjoyable Matters", the final one of which was "playing qin for an understanding listener". The 16 (translation incomplete) were:

- 蘇東坡:人生賞心十六樂事

- 清溪淺水行舟 In the shallow waters of a clear stream to ride a boat

- 微雨竹窗夜話 With light rain outside a bamboo window have an evening conversation

- 暑至臨溪濯足 When summer comes, in a clear stream wash your feet

- 雨後登樓看山 After rain to climb a tower and look at mountains

- 柳陰堤畔閒行 Along a willow-shaded embankment have a leisurely walk

- 花塢樽前微笑 Huawu tea, a cup (of wine), then smile

- 隔江山寺聞鐘 Between a river and a mountain temple to hear a bell

- 月下東鄰吹簫 Under the moon the Eastern Neighbor (i.e., a beautiful woman) plays xiao flute

- 晨興半炷茗香 In the morning arise in half light to tea fragrance

- 午倦一方藤枕 When tired at mid-day to have a rattan pillow

- 開甕勿逢陶謝 Open a (wine) vat but not meet Tao or Xie (who would drink it all)

- 接客不著衣冠 Meet a guest with whom you don't have to get dressed up

- 乞得名花盛開 Seek a lovely flower (beautiful woman) and it/she blooms

- 飛來家禽自語 (A child who has) flown home like a bird speaks

- 客至汲泉烹茶 When a guest arrives to draw water and boil tea

- 撫琴聽者知音 Play qin with a listener who understands (your) music

- 微雨竹窗夜話 With light rain outside a bamboo window have an evening conversation

Su Dongpo: For a happy mind, 16 enjoyable matters

See related image.

(Return)

Return to top or to the Guqin ToC