|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Qinshu Cunmu Annotated handbook list Melody names Zequan the Monk More on rhythm | 首頁 |

|

Qinyuan Yaolu 1

Anonymous; Qinshu Cunmu #99, 2 11 lines Facsimile edition published in Beijing 3 |

琴苑要錄 1

無姓名 Cover of facsimile edition (pdf 3) |

This anonymous handbook is said to date from the 13/14th centuries, but it consists mostly of material copied earlier sources and its two known surviving versions clearly have later additions. It is thus not possible at present to say what, if anything, was included in any publication of this title actually dating from before the Ming dynasty.

Table of Contents (Beijing facsimile edition)

(Page reference 1/2 means second part of double page 1)

I. Qin Cao 琴操 (missing: the 5 Melodies and 21 Hejian Zage as in the Pingjin Guan edition ToC) 1/1 (上海#1)

QSCM #10,

#12 and #18 are all Qin Cao.4

Compare the Pingjin Guan edition

- Jiang Gui Cao (將歸操)

- Yi Lan Cao (猗蘭操)

- Gui Shan Cao (龜山操)

- Yueshang Cao (越裳操)

- Ju You Cao (拘幽操)

- Qi Shan Cao (岐山操)

- Lü Shuang Cao (履霜操)

- Zhao Fei Cao (朝飛操)

- Bie He Cao (別鶴操)

- Can Xing Cao (殘形操)

- Shui Xian Cao (水仙操)

- (Huai Ling Cao 懷陵操 missing!)

- Yi Lan Cao (猗蘭操)

B. (9 Preludes) (yin; this title is missing) 6/1

Compare the Pingjin Guan edition

There is no tablature here, but these melodies all do include commentary.

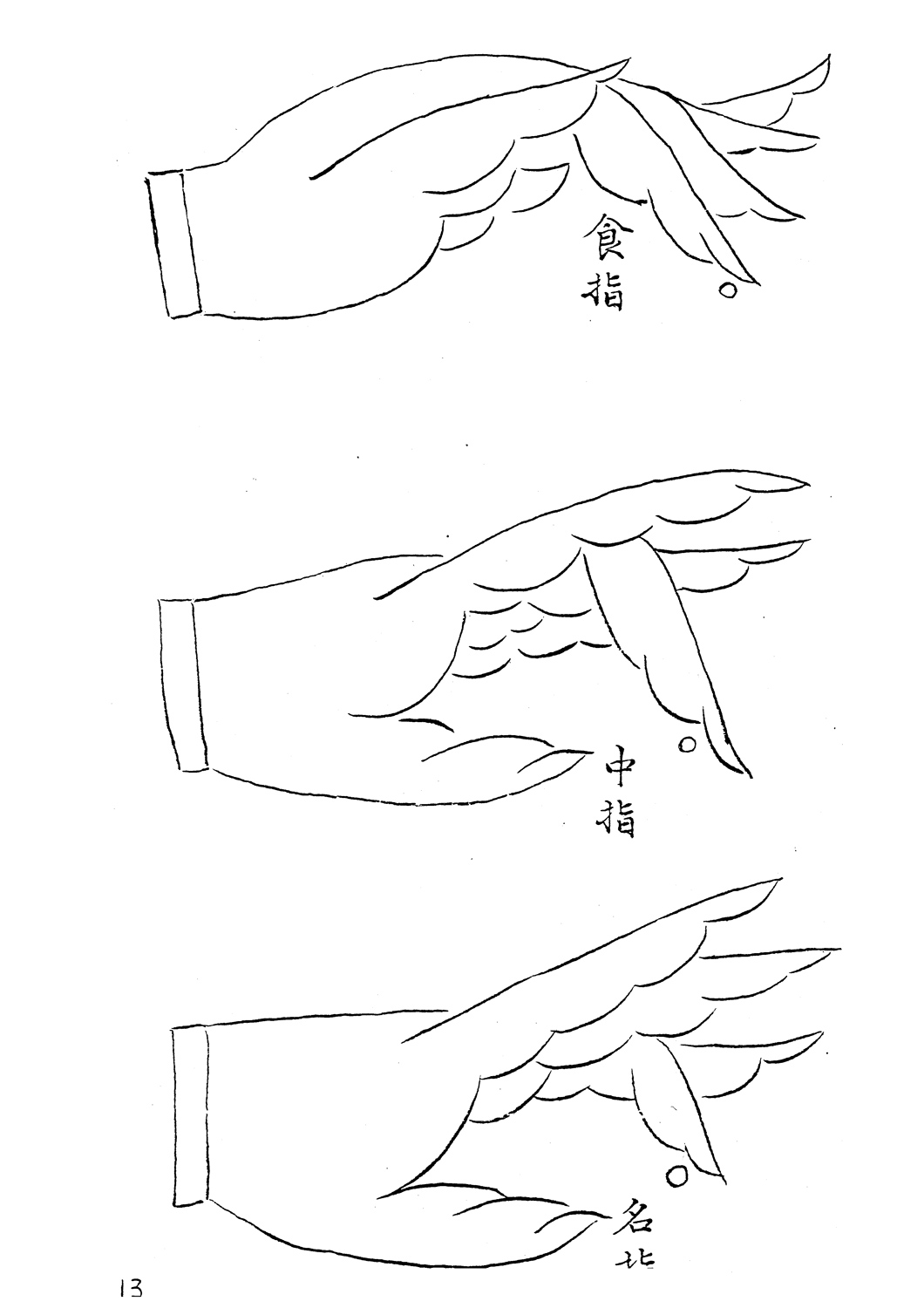

| Finger methods diagram #1 (complete pdf) |

II. Zequan Heshang (則全和尚): Rhythm and Fingering (節奏指法) (originals) 11/1 (上海#2 節奏)

II. Zequan Heshang (則全和尚): Rhythm and Fingering (節奏指法) (originals) 11/1 (上海#2 節奏)

See QSCB, Chapters 6c6

(Rhythm and Finger Methods and 6b3 (Diaozi and Caonong)

Also see QSCM, #97 but not QSDQ

Folios 8 or 9; here "fingering" comes before rhythm.

The actual date of the illustrations, as at right and in this

fingering pdf, is not certain.

Are they precursors of the images later paired with symbolic representations and explanations, as here?

- (An opening preface by the editor, apparently named

曹摭 Cao Zhi)5 11/1

- the translation and original text are given below. - Finger methods 6 12/1

- "Whenever placing the finger down, first let it settle onto the string before applying pressure; one must not slap the finger down directly in a loose or uncontrolled motion...." - Finger diagrams and explanations 13/1 (continue 上海#2)

- 23 right then 10 left (complete pdf) - Rhythm 7 29/2 (continue 上海#2)

- see also Yi Hai; discusses Zui Weng Yin and Ting Qin Yin; from Yi Hai ("海大師")?;

- says "Each qin piece has its own framework. For example,...";

- see translation and original text; compare 1525 version

III. 琴書 Qin Shu (Qin Book) 34/2 (上海#3)

QSCM, #96 (not #44). Some have attributed this to Zhao Yeli. 8)

- (製琴 Making a Qin -- Why not this section title?)

制造 Construction; quotes 李勉 Li Mian, 琴記 Qin Ji (琴說 Qin Shuo? 琴yi說 Qin Shuo?)

and 齊松 Qi Song, 琴記 Qin Ji; 34/2

製琴法 Construction methods 36/2

煎黳光法 Boiling wood for brightness method 40/1

合琴光法 Mixing for bright qin method 40/2

退光出光法 Taking off brightness and bringing out brightness method 41/1

造絃法 Making strings method 41/1

煮絃法 Boiling strings method 42/2

纒絃法 Wrapping strings method (with illustrations) 43/1

辨徽 Explaining the studs (hui) 44/1

辨音 Explaining the tones (yin) 45/2

彈法 Playing method 47/2

辨徽 Distinguishing hui markers

辨音 Distinguishing sounds

彈法 Playing method- 琴說 Discussing Qin (beginning with 琴錄 7 rules?) 49/2

十悪 10 uglies

五不彈 5 no-plays 50/1- 辨曲 Distinguishing melodies 50/1

曲名 Melody names (99+57+97) 50/2- (指法 Finger techniques)

Figures for right hand strokes 54/1

Figures for left hand strokes 54/1

Method of combining these figures 54/2

Right hand finger techniques 54/2- 善琴 Praising the qin 56/2

- Zhi Xi Preface (止息序 Zhixi Xu; compare Lü Wei).9

- Liezi says, 瓠巴 Hu Ba played the qin

- Annals of History says 晉平....(see Shi Kuang)

- Shuo Yuan says, (Yongmen Zhou story) - 琴說 Discussing Qin (beginning with 琴錄 7 rules?) 49/2

This essay, tentatively dated from the Tang dynasty, is thought to have been written as a preface to a collection of qin-style images. Many such sets of images have survived from the Song dynasty and later. Were these the earliest? In any case, this essay suggests it has an appendix with such images, but then appendix no longer survives.

The entire surviving essay is in this footnote, with translation.11

V. Cutting Qin Methods (碧落子,

Zhuo Qin Fa 斲琴法)

QSCM, #125, by Biluozi (石汝礪 Shi Ruli) 60/1 (上海#6)

- Fixing the size of materials 60/2

- Size of the qin body 61/1

- Paring the surface method 62/1

- Tuning the sounds method 62/2

- Comparing the size of old qins method 63/2

- Qin color style method 65/1

VI. Cutting Workmens' Secrets (斲匠秘訣)

QSCM, #133, anonymous

- 目錄 Table of contents (66/1 上海#7)

- 選材 Selecting Materials (66/1)

- etc. (20 items)

VII. Qin Commentary (琴箋 Qin Jian) 73/2 (上海#8)

QSCM, #92; by (Song) Cui Zundu (崔遵度), aka Cui Jianbai (字堅白); discussed in QSCB, Chapter 6c4.

VIII. Continuation of Qin Commentary (續琴箋) 75/2 (上海#9)

QSCM, #132; author unknown

IX. Fengsu Tong, Discussion of sounds (風俗通,音聲論) 77/2 (上海#10)

This passage from

Feng Su Tong is also quoted in QSDQ, but the end is different.

12

Tacked on at end: a passage from the Xin Lun by Huan Tan discussing the origins of the qin.13

X. Qin Discussion (琴論) 78/2 (上海#11)

QSCM, #67; by 姚兼濟

Yao Jianji (see original text translation14)

The Tieqin Tongjianlou Shumu edition of Qinyuan Yaolu, now in the Shanghai Library, ends here. However, the Beijing reprint appends here (p. 80/1) a brief comment by 馮水 Feng Shui, who in 1925 apparently made a new hand-copy of the whole book, making some corrections and editorial revisions. This edition is now in the 中國藝術研究院圖書館 library of the China Art Research Institute, Beijing, and is apparently the source of the facsimile edition I began working with.

After that the 太音大全手訣 Hand mnemonics said to be those in

Taiyin Daquanji were added as an appendix, apparently for comparison purposes (see Section 2 / 上海3). As can be seen, here the illustrations and explanations are somewhat different.

The Beijing edition then has another afterword by Feng Shui.

I am still not sure about many things concerning this book. In particular, considering its apparent 1518 date of publication as well as its hand-copied nature, it would be good to know which materials only survive because of inclusion here.

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

琴苑要錄 Qinyuan Yaolu references

Qinyuan Yaolu is mentioned in various places on this site, including,

21570.xxx; 中國音樂思想批批判 Zhongguo Yinyue Sixiang Pipan (1965), pp.149/150, mentions two available editions, 瞿氏舊藏明抄本 (Old Ming copybook in the collection of the Qu Family), and 據明抄本傳抄晒印 (A blueprint [?] based on the Ming hand copy). The Qu family edition was in their Iron Qin Bronze Sword Tower (鐵琴銅劍樓

Tieqintongjianlou Shumu). Zha Fuxi's Preface to Wusheng Qinpu says, "The original copy was in the collection of the Qu family of Changshu, but now it has been returned (sic) to the Beijing Library. It is a sister volume (revised from) a hand copy of Qinyuan Yaolu in a collection dating from the Zheng De period (1506-22)." Qinshu Cunmu (see below) makes no mention of Wusheng Qinpu, saying instead that it was together with Qin Shi.

(Return)

2. Qinshu Cunmu entry 99 says it is 舊抄本 an old handcopy, then writes,

Based on the date of the last essay in the book, it seems that the book itself, though consisting mostly of ancient essays, or quotes there from, was not actually compiled until the early 16th century.

(Return)

3.

Facsimile edition of 琴苑要錄 Qinyuan Yaolu

The edition linked above is a copy in the Shanghai Library, downloaded from

here, whereas the facsimile edition I have was apparently published in Beijing, though it gives no publication details. The Shanghai Library version seems to have no page numbers so all the page numbers given here are from the Beijing edition.

Although the order between the two editions seems to be basically the same, there have been some revisions in the Beijing edition. I have not yet put the two editions side by side and so at the present moment

In my facsimile edition the hand mnemonics called 太音大全手訣 Taiyin Daquan Shoujue Hand Mnemonics were apparently added to the Beijing edition from Taiyin Daquanji as an appendix for comparison. The Qinyuan Yaolu from the Shanghai Library, apparently a copy of the version that was in the Iron Qin Bronze Sword Tower (鐵琴銅劍樓 Tieqintongjianlou, does not have these.

The afterword by 馮水 Feng Shui in the Beijing edition begins as follows:

Feng Shui is also connected with some other publications from the "early Republic" (see, e.g., in Zha Guide).

(Return)

4.

(Excerpt from) Qin Cao

What is included in this edition of Qinyuan Yaolu actually begins with a section called 古操十二章 12 Old Laments, but the section introduces 20 melodies. If compared with the 平津館 Pingjin Guan edition of 蔡邕琴操 the Qin Cao of Cai Yong (see

editions), it can be seen that this Qinyuan Yaolu edition has the first 11 of the 12 cao, then (without a heading) the nine preludes (引 yin) which form the middle two sections of the Pingjin Guan edition. Here the title of the 12th cao and a heading for the nine yin have been added.

(Return)

5.

Preface (QYYL p.11/1)

Here is a translation followed by the original text attributed to 曹摭 Cao Zhi:

"'Qin' signifies 'restraint'"; restraining lasciviousness leads to correct sound.

To play the qin, one must first align and stabilize the mind, calming thoughts before laying out the qin in front of you. When the heart is lined up with the fifth hui position, one should gradually adjust the strings, ensuring that the tones and rhythms are clear and elegant. Whether it is a short warm up piece (? a modal prelude?) or a proper qin melody, begin slowly, then increase the pace, and afterwards return to a slow rhythm. Then when calm play one or two pieces then pause again. And after playing a light piece, when the spirit is clear and the 氣 energy is in balance, the hands movements will be loose and relaxed, and so when you play a significant piece you will naturally express its meaning. The ancients valued the qin not for its quantity: it is sufficient to master just one piece well. Those who can truly appreciate music will request this piece played several more times so as to grasp what it was the ancients appreciated in it. Nowadays, when listening to the qin, people seek exciting pieces, ones that are not really worth hearing, wild sounds like those of the zheng zither, pipa lute and jiegu hand drum. By prioritizing what is easy on the ear just for immediate pleasure, what they hear is void of any depth. How lamentable this is!

As for learning to play the qin, one should first learn to position the fingers to achieve the high and low sounds, keeping the rhythm without losing its structure, which will naturally lead to mastery of the music. Each qin piece has its significance. For example, "Guangling San" is divided into an "Initial Prelude", a "Postlude", a "Main Section", "Concluding Tones" and "Realize the meaning of "Stop for a Breath", forty-four sections in all, created by Xi Kang to reflect the turmoil of the Jin and Wei dynasties. "High Mountains" and "Flowing Water" show Bo Ya expressing his feelings about forests and streams. "Autumn Thoughts," "Welcoming Spring," "Green Waters," "Sitting in Sadness," and "Quiet Abode" are attributed to Cai Yong, as they reflect his meeting with Gui Guzi. "Zhaojun's Lament" is of unknown authorship but symbolizes her departure from the border. "Li Sao" mourns Qu Yuan, and "Sorrowful Winds" was created by Confucius reflecting on the transformations brought about by Yu and Shun. Other pieces come from later generations of people who have changed the style, not just missing the but places were the ancients expressed their feelings, but using garbled finger techniques and rhythms without coherence. How is this any different from the sounds of the zheng, pipa, and drum?

This humble servant, while accompanying my late father during his official travels, because we happened to enter a chamber to burn incense, gained the acquaintance of a monk from Shu (Sichuan) named Jujing (Dwelling in Stillness), style name Yuanfang. He directly instructed me that, "Every time I play the qín, it may be I who plays it, but it is playing me as well; in that moment, I attain sudden insight and understanding flows."

I, a great-grandnephew of Empress Cao, named Zhi, style name Guihuo, thus obtained the precious volume by Zequan the Monk and thus am transmitting it further. Over more than thirty years I have seldom encountered anyone who truly understands music and so I dare not conceal this. Though limited in my own understanding, I have recorded this general outline of fingering that goes before (qin) tablature, hoping it will help students of further generations not to misplace there efforts. How fortunate this will be!

(N.B., on this basis the author's name is said to be 曹摭 Cao Zhi, though his style name is elsewhere given as 貴荻 Guidi; "Empress Cao" (1016-1079;

Wiki) fits the time frame of the consort of the Renzong emperor . The explanations perhaps accompanied tablature of Zequan's teacher, 義海

Yi Hai. See also

here.)

則全和尚:節奏指法

琴者禁也,禁其邪淫則其聲正也。 (See Huan Tan, Xin Lun)

凡欲彈琴,先端正定心,息慮横琴面前。今五徽與心相對,緩緩調絃,迤還調令聲韻清雅。或若調子,或若琴曲,先緩次急後卻緩,必息候人静方彈。調子一兩弄又少息,且彈小操弄候神清氣和,手法順霤,方彈大操,自然得意。蓋古人好琴,不在多,但一操得意而已。能聽之者令再三彈此一曲,方識古人用意處。近時聽琴,便欲熟鬧,堪聽不得,已雜以箏、琶、羯鼓之音。貴其易入耳以取一時之美,聽全失古意,豈不嘆哉。

凡學彈琴,先學立指取聲高下,節奏不失其規矩,自然造其炒理。琴操之作,各有意焉。如《廣陵散》,曲分《前序》、《後序》、《正聲》、《亂聲》,《會止息意》。凡四十四拍乃嵇康所作,以誘晉魏之亂也。《高山》、《流水》乃伯牙得意,林泉也。《秋思》、《迎春》、《綠水》、《坐愁》、《幽居》蔡邕以為䞇見謁鬼谷子也。《昭君怨》不知何人所作,象其出塞之時也。《離騷》弔屈原也。《悲風》者孔子作,以思虞舜之化也。其他操弄被後人增減,非止不得古人用意處,而又指法錯亂,節奏無度,聲韻繁雜,何異箏、琶、羯鼓之聲。

僕侍先子宦遊因入室燒香,得蜀僧居靜字元方。直指云:「每彈琴,是我彈琴;琴彈,我當下頓悟,後通。」

曹大后之姪孫名摭,字貴擭,得則全和尚妙本,遂傳授之。凡三十餘年,少遇知音者,不敢自隱。耶聊以短見,叙指之大概於曲譜之前,庶幾後之學者不悞用心焉。幸甚!

See the above comment.

(Return)

6.

Zequan Heshang on fingering (QYYL 11/2-29/1)

The original text begins,

The instructions here should be compared to those from Ming handbooks.

(Return)

7.

Zequan Heshang on rhythm (QYYL 29/2-34/1 [10 pp])

My draft translation followed by a copy of the

original text are in the Appendix below.

The comment above suggests the original was written by one Cao Zhi based on material from Zequan Heshang. See also the comments

in QSCB.

(Note that the lengthy article in Xilutang Qintong [1525]) about rhythm seems largely to copy material from the article here.)

(Return)

8.

Qin Shu

The description in Qinshu Cunmu #96 begins "不著選人名氏,是編載名抄本琴苑要錄,"Anonymous; this book was included in the handcopied Qin Yuan Yao Lu...." See also the Shen Qi Mi Pu Preface comment about Qin Shu. Is this the same book as that mentioned by Wang Shixiang in a footnote of his Guangling San article? In his comments on the Qin Shu in Qinyuan Yaolu, Wang quotes from the version above then adds that 周慶雲,琴書存目 Zhou Qingyun's Qinshu Cunmu includes a Qin Shu written during the 景祐 Jingyou period (1034-38) of the Song dynasty (see QSCM #96 [Folio III, #8]).

From this it is not clear whether, other than here, there are any further references to the content of this book.

(Return)

9.

Zhi Xi Preface (止息序 Zhixi Xu), from 善琴 Praising the qin 56/2

This story is similar to the one told with

Lü Wei, who is said to have added to the tablature. The version here was translated into German by Manfred Dahmer, who dated it to 1035 CE; see Der Lange Regenbogen, Die Solosuite Guanglingsan für Qin; Uelzen, Medinizinisch Literarische Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 2009; pp. 86-87 and 111-112. The original text is as follows (punctuation and some corrections from Dahmer):

Tentative translation:

“Zhi Xi” refers to the piece known as “Guangling San.” Ji Kang, also known as Ji Shuye, contemplated the netherworld and received this melody through divine inspiration. At that time, the deity stipulated that it must not be heard by others; violating this would bring misfortune. For several years, Ji Kang would play this piece only in secluded mountains and forests, places devoid of people. A friend, Yuan Xiaofan (also known as Yuan Xiaoni), was also skilled at playing the qin and wished to hear the piece, but had no means to do so. He feigned death. Ji Kang often said, “Thinking of him, who wished to hear ‘Guangling San’ throughout his life but died without the chance—now that he is dead, is it permissible to play it?” Moved by these words, Ji Kang dismissed others, took up the qin, and played. Yuan Xiaoni, being exceptionally intelligent, grasped it upon hearing. Ji Kang was indeed executed—was this not the divine’s doing? The piece has been transmitted to the present through Yuan Xiaoni.

It comprises forty-one sections: five sections serve as a preface, narrating the story, akin to a poetic introduction; eighteen sections form the main body; another eighteen sections represent the harmony, signifying unity with spirits and deities; eight sections express the intent of “Zhi Xi,” symbolizing cessation. Examining its notation and playing its sounds reveals the profound essence of the Dao. Its expressions of resentment and sorrow resemble the voices of spirits from the netherworld—solemn and serene, with words clear and cold. When it becomes agitated and impassioned, it resonates with thunderous echoes, like wind and rain, radiant and resplendent, with weapons clashing. To speak of it briefly cannot capture its full beauty.”

The essay in Qin Yuan Yao Lu continues with a passage from Liezi (列子曰:

瓠巴鼓琴,鳥舞、魚躍。師文聞之....).

(Return)

11.

Qin Shenglü Tu 琴聲律圖 (Qin Sound Rules Diagrams 59/1; [上海#5])

Here is the original text of this essay with translation. Attributed to 西平麴瞻撰

Qu Zhan of Xiping, it is tentatively dated from the Tang dynasty.

- 琴在金石最優,於絲竹尤妙。有青龍鳳篆,有鸞鶴聲。

雨雪風雲應節,彩春秋冬夏隨音變時。

千年一聖生,存其雅操;百代幾廢,禮無歇其芳聲。

盡妙矣!盡善矣!

乃雙鳳連綿之音,雙鳬綺靡之韻。

飛龍七縱,鳴鹿九成。

(岌)峨者山,蕩蕩者水。

宮、商之不是少宮、少商。角、徵之有條聞清角、清徵。

曲度榮會,調緒紛淪。

動絃有音,發律有應。

既隨手多變,當紀律成規。

始伏羲造琴,終嵇叔夜作賦。

(伯)牙、(師)曠必時,浮(英)敘;(蔡)邕、固日用不知,千古聞。

Among metal/stone instruments (ritual ensembles), the qin stands supreme; among silk/bamboo (secular ensembles) its subtlety is unparalleled, Adorned with azure dragons and phoenix seals, voiced by simurghs and cranes. Rain, snow, wind, clouds answer to its rhythms; the hues of spring, autumn, winter and summer shift with its tones. Once in a millennium, a sage preserves its elegant art; though rites fade through ages, its sublime voice endures. It is perfect in craft, perfect in virtue! It is the sound of twin phoenixes in harmony, the cadence of paired ducks in splendor. Soaring dragons cascade sevenfold; crying deer resonate ninefold. Lofty as mountains, boundless as waters. (The notes) gong and shang differ from their shaogong/shaoshang variants (being an octave higher); (the notes) jue and zhi are disciplined through qingjue/qingzhi (a half step different). Melodic contours converge gloriously; modal threads interweave. Pluck a string and sound emerges; sound a pitch and harmony responds. From Fuxi who created the qin, to Ji Kang who composed a rhapsody on it. Boya and Shi Kuang mastered timely expression, their brilliance narrated; Cai Yong and Gu [Kangcheng?] used it daily, unaware (of musical theory), yet their fame echoes eternally.- 六律無絕。西平麴瞻,字宣遠。 代王侯伯子男,居仁義禮智信。 琳琅為質,黼繪為文。明在月中。

The Six Pitch Standards enduring unbroken, I, Qu Zhan of Xiping, styled Xuanyuan, representing nobles and commoners alike, abide by benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and fidelity. My substance is jade and pearl; my refinement, brocade and embroidery. My clarity dwells within the moon.- 越塵外好,古雅頌樂;道管絃處,則琴室風亭。 出則琴書風月。春歸「姑洗」,顧「幽蘭」成詞;律中「黃鍾」,持「白雪」為調。 伐柯取則立。

Transcending worldly dust, I cherish ancient elegance as well as the odes and music; where pipes and strings resound, my qin pavilion stands amid breezes. Abroad, I carry qin and texts through wind and moon. When spring returns to guxian (pitch), "Secluded Orchid" inspires poetry; when Huangzhong (pitch) sounds, "White Snow" becomes the melody. Thus, the axe-handle’s pattern guides the cut.- 垂芳別絃絲之豪芒,定音韵之洪(殺)。 錯十二律,撃三百聲。 撃「中呂」則清明風生,扣「無射」則閶闔風至。 「角」、「羽」得之以蹈舞,「金石」得之以克諧。 豈煩緒練?緗即當處注記札。 樂後進指掌,無違。

Refine silk strings to hair-breadth subtleties; fix tones between resonance and restraint. Array the twelve pitches; strike three hundred notes. Strike zhonglü (pitch) and spring breezes arise; pluck wuyi (pitch) and cosmic winds descend. With (the pitches) jue and yu, dance takes form; with metal and stone, harmony is achieved. Why vex with tangled silk? On golden silk, I inscribe notations then and there. For later learners, this guides the hand — unerringly.- 呂先鳴,知音不悞。直書其事,名曰「琴聲律圖」。 君子甚哉!此其善事。非夫思深志遠,斯焉取斯? 足以貽厥樂章,施之座右者矣。 琴有十二家樣,形體有殊,分寸俱別。 至於習者能悉焉,貽諸弟子曉悟將來。 恐未識其意,圖列之於后。

(十二家琴樣,見別本。)

When pitches first sound, those who understand sound do not mistake them. I record these matters plainly, titled "Qin Sound Rules Diagrams." Noble is this task! None but the profoundly thoughtful and far-visioned could grasp it. Thus, I bequeath this musical canon to display at one’s desk. There exist twelve qin models — distinct in form, differing in measurements. One must be a practitioner to recognize them. So I bequeath this to disciples so that they will be enlightened. Fearing that otherwise they will fail to see the significance, diagrams have been attached after this.For these Twelve Qin Models, see in a separate volume.

- 六律無絕。西平麴瞻,字宣遠。 代王侯伯子男,居仁義禮智信。 琳琅為質,黼繪為文。明在月中。

As for 殺 , it was actually written by combining 食/煞! The 固 Gu [4842.] from the first section may be a misprint for 鄭玄 Zheng Xuan [40513.77], style name 康成 Kangcheng, 127-200; Zheng worked with Cai Yong

[Wiki].)

Return

12.

風俗通音聲論 Musical Sounds Essay from Feng Su Tong

Begins, "謹按世本神農作琴。尚書舜彈五絃之琴以歌南風..." (21 lines)

(Return)

13.

新論 Xin Lun passage discussing qin

Begins, "桓譚新論曰,神農、伏羲氏之王天下也。削桐為琴,長...." (7 lines)

DeWoskin, Song, p.115, includes the translation by Timothy Pokora (see details) of this passage. It includes the following description:

Above it was circular and gathered in, following the model of Heaven; below it was square and flat, following the model of earth....

Clearly this is describing the rounded top and the flat bottom that one finds on all qin. The translation may thus be somewhat misleading. In an article from 2007 on early qin-type instruments Prof. Bo Lawergren interprets this passage as referring to round and square areas on the early qin-types, then compares this with the two sound posts now found inside the qin (in the reverse direction), the rounded one called tianzhu (heavenly pillar), the square one dizhu (earthly pillar). Yuan (圓) means rounded as well as circular and lian (歛 or 斂) seems to suggests the way it meets the flat surface. Fang, in addition to "square", can also suggest rectangular (e.g., it can refer to a wooden tally, which was rectangular).

(Return)

14.

姚兼濟琴論 Qin Essay by Yao Jianji (QSCM, #67)

The text of the essay is as follows:

夫古弄之声,冷淡清邪。是古人質直,随意成声,俱全五音,達意而已。 泊乎周代,文武二王,運思精巧,特加少宫、少商,合成七音,以象七星也。 夫声調之声,清莫不欲其和平應切,意頗尽矣。 又蔡公琴操曰:「大絃者,君也,宽和而温;小絃者,臣也,清庶而不乱。」斯之謂矣。 琴者,禁也,摠樂之主,氣略乾坤。上以應神明,下以和風俗。况人心五常,天性者也。 夫宫声之感情也,其意悲楚;商声之感情也,其意優逸;角声之感情也,其意歡和;徵声之感情也,其意凄凉;羽声之感情也,其意流平。此之謂也。

正德戌寅孟春廿又六日,安愚録畢於三速齋。

Yao Jianji's Treatise on the Qin

The sound of ancient qin melodies is cool, tranquil, pure, and upright. The ancients, being straightforward in character, produced sounds naturally, encompassing all five tones sufficently to convey meaning.

By the Zhou dynasty, Kings Wen and Wu applied refined ingenuity, adding (the two strings representing the notes) shaogong and shaoshang to form seven tones, and symbolizing the seven stars. In tonal regulation, clarity must always seek harmony and precision — this exhausts its intent.

As Cai Yong’s Qin Cao states: "The thick string is the ruler — generous, harmonious, and gentle; the thin string is the minister — clear and orderly without chaos." This is its meaning.

The qin is a restrained instrument, the sovereign of music, its energy encompassing heaven and earth. Above, it resonates with the divine; below, it harmonizes customs. Moreover, the human heart’s five constants are innate to nature.

The gōng tone stirs emotions of sorrow and longing; shāng evokes elegance and ease; jué brings joy and harmony; zhǐ conveys desolation; yǔ flows with serenity. This is its nature.

Completed and recorded by An Yu on the 26th day of the first lunar month, 1518, at the San Su Studio.

That is the end of the book.

(Return)

Return to the annotated handbook list or to the Guqin ToC

Appendix

則全和尚:節奏指法

The Monk Zequan’s Rhythmic and Fingering Techniques

Translation and original text (QQJC V/206-9)

Translation below still in progress

- On the Modes and Their Characteristics (凡琴操各有格):

Each qin piece has its own framework. For example, gong, shang, jue, zhi and yu are modes that do not call for changing the relative tuning. (Yet they differ in that) gong mode melodies are harmonious and balanced; shang are clear and bright but with shorter resonance; jue and zhi are slower, conveying a sense of sorrow; and yu is plaintive, capturing its essence. As for the non-standard modes (requiring changing the tuning), though acoustically intricate, they tend toward the decadent sounds of Zheng and Wei music, leading to what is termed “mixing purple with vermilion,” implying a loss of purity.

- On pin (凡品)

The ‘pin’ style differs entirely from the ‘diaozi’ style, requiring swift dynamics. Modern players often perform diaozi as if they were ‘caonong’ (操弄), neglecting rhythm.

- On pin (凡品)

they resemble singing a slow tune: one takes a breath before the beat and connects phrases seamlessly. In diaozi, each beat starts with two slow notes, followed by several notes, a brief pause, then holding a note before transitioning to the next phrase—this is called “double start, single end.” For example, in “Drunken Elder’s Tune”: the words “Lang Ran” are played slowly; “Qing Yuan Shui Tan Jing Kong Shan, Wu” is followed by a pause; then “Yan Wei Weng” connects to the next phrase. Other pieces follow this pattern.

- On ‘Caonong’ (凡操弄):

In caonong, each phrase begins with a leading word; at the end, there’s a pause, holding two notes before connecting to the next phrase, contrasting with diaozi. If learners grasp these three aspects, they can distinguish between pin, diaozi, and qu (曲).

On Music Sections (凡樂部之曲):

Traditional compositions, influenced by the music of Zheng and Wei, evolved from guqin pieces. Aspiring guqin players should first study these compositions, understanding their structures: slow two, fast three, slow four, fast seven. In slow pieces, the transitions—smooth, abrupt, penetrating, dragging—mirror guqin rhythms: vibrato, sliding, tapping, pressing, with breath taken before the beat and subtle sounds amidst noise. In grand compositions, techniques like preemptive strikes, breaking entries, and resting beats resemble major caonong rhythms. Recognizing the opening of a tune enables one to play pin; singing slow tunes aids in playing diaozi; mastering the breakdown of a piece leads to proficient caonong. With proper fingering, the intentions of ancient masters become evident. However, it’s unnecessary to learn extensively; focusing on one pin, two diaozi, and one caonong, as per my compiled methods, allows for specialized mastery, aligning one method with myriad techniques. Contemplating silently leads to profound understanding, achieving subtlety upon subtlety, intricacy upon intricacy. If my words are deemed appropriate, it would be most fortunate.

- On Rhythmic Intentions (凡琴操):

In qin pieces and diaozi, the concepts of initiation, development, and resolution may occur within a phrase, several phrases, a section, or an entire piece. This reflects the ancient masters’ deep emotions, restlessness, and constraints. Rhythms may correspond between two characters, phrases, or sections, with variations in pitch, weight, length, and speed. As Han Yu’s “Listening to the Qin” poem states:

“Whispers of affectionate words between lovers;

suddenly transformed into the rising spirit of warriors charging into battle.”

The clamor of a hundred birds; amidst them, the sight of a lone phoenix.”These truly capture the essence.

- On Rhythmic Variations (假令用蠲):

If a ‘juan’ is used, and another follows, one must employ overlapping juan, double juan, or even continuous juan; this progression from few to many, and vice versa, exemplifies rhythmic finesse. Master Yihai once said: “As swift as countless stars without chaos; as gentle as flowing water without end.” In guqin pieces, when approaching a pause, anticipate the next phrase’s onset, retaining the final note of the previous phrase to connect seamlessly. This requires “releasing tension in dense parts, tightening in sparse parts.” Capturing the tonal essence should avoid abruptness; one must leave a trace of resonance, transitioning to the next phrase at the point of incompletion, termed “meaning beyond the notes.” As the saying goes: “Tasting an olive, one seeks its lingering flavor.” Understanding this deeply aligns with the ancient masters’ intentions. (It’s akin to cursive script, where silent strokes connect characters.)

- On Fingering Techniques (凡對按):

Techniques like pressing, lifting, striking, and plucking also possess rhythm; embodying the principle of “tightness within looseness, looseness within tightness.” For instance, when using striking and plucking, they shouldn’t be continuous but divided into two distinct sounds, ensuring clarity in dense sections. Final notes, picking, hooking, lifting, striking, and plucking should follow this pattern: the preceding character aligns with the previous phrase, the succeeding character with the next.

- Examples of Specific Techniques (假令....):

For example, when using the tenth position to strike the third string, named the eleventh, align it with the ‘dao’ technique; first set the third position, pause briefly, then apply the lifting sound with a slight vibrato, connecting to the next phrase. The scattered ‘tao’ five connects as a single sound, exemplifying “looseness within tightness.”

- More examples (若是):

If employing striking, plucking, pressing, lifting, and ‘tao’ five, begin with a strike, pause briefly, then combine plucking, ‘dao’ lifting, and ‘tao’ five into a single sound. This is because ‘tiao’ five belongs to the subsequent phrase.

- On Ornamentations (凡吟猱):

Techniques like ‘yin’ (vibrato), ‘rou’ (sliding), and ‘yin’ (pulling) should follow the completion of a note, allowing the residual sound to settle without confusion. Learners often misuse ‘yin’, failing to wait for the note’s completion, instead moving fingers back and forth on the string, mistaking it for novelty, thereby disrupting rhythm. For upward slides, one must first apply vibrato before sliding up; for downward slides, descending naturally leads to ‘nao’ (a specific technique).

- On Expressive Techniques (凡前聲):

When a preceding sound employs ‘yin’ or ‘nao’, the subsequent sound shouldn’t fear overlap; the same applies to pulling and other techniques.

- On Mental Preparation (凡彈操弄):

Before playing caonong, one must first calm the mind, avoiding distractions. Adjusting dynamics and pitch within a piece is at the player’s discretion, not dictated by finger movements, naturally achieving the desired expression.

- Examples from Yi Hai and Han Yu(義海、韓愈):

Master Yihai stated: “Clouds floating in the vast void, shaped by the wind into myriad forms, never losing their natural charm.” Han Yu also remarked: “Floating clouds and willow catkins, rootless, drifting across the expansive sky.” This place embodies ancient sentiments.

- On Purposeful Composition (凡操弄之作):

Each caonong is crafted with intent. Modern learners often play numerous pieces with indistinguishable sounds. For instance, “Spring Outing” and “Secluded Dwelling” differ in tone and meaning. A particular piece begins with Shun’s song “South Wind,” utilizing external harmonics, later transitioning to a melancholic tone. “Li Sao” mourns Qu Yuan; “Zhao Jun’s Lament” imagines her departure beyond the frontier. Their complex, overlapping sounds resemble women’s laments. “High Mountains” and “Green Waters” genuinely reflect the essence of forests and springs, aligning with the original intent of naming caonong.

- On Sliding Techniques (凡引上):

Upward slides mustn’t exceed limits; downward slides, pressing down, are acceptable, as they harmonize with subsequent sounds. As the saying goes: “Climbing requires measured steps; overreaching leads to a steep fall.”

- On Tuning (假令大絃):

When tuning, first assess the general pitch, selecting one string as the reference, then adjust others accordingly. Too tight, and strings may break; too loose, and they produce no sound. A balanced tension yields optimal sound. Modern learners often over-tighten strings for higher pitch, believing it sounds clearer, but this sacrifices

- (凡調絃):

(This section has specific fingering instructions not yet clarified.)

- On discussing rhythm (凡云節者)

In qin performance, it is essential to regulate complexity and tempo to avoid chaotic or excessively rapid passages, as well as overly slow and unstructured ones. The techniques of ‘yin’ (vibrato) and ‘nao’ (rolling) should exhibit rises, degrees, and falls that align with the rhythm. Within a piece, three to five phrases may naturally form a small section. Begin with an initial phrase, pause briefly, then play several phrases, leaving two notes to connect swiftly to the first phrase of the next section, followed by another brief pause. Maintaining this consistent rhythm from start to finish allows the piece to flow naturally and slowly into a complete composition.

Modern players often lack understanding of this principle, playing as if beating a drum without recognizing the conclusion — truly a laughable matter! This greatly deviates from Master Yihai’s statement: “As rapid as a myriad stars without confusion; as slow as flowing water without cessation.” Such is a significant flaw in qin playing; those who understand music should pay close attention.

- Example from Han Yu (唐韓退之):

Han Yu’s “Listening to Master Ying Play the Qin” (says),

Affectionately whispering a young boy and girl speak, in fondness or anger they (call) each other "dear".

Abruptly it changes to the heroic, brave warriors charging to the battle field.

And then:

Floating clouds of willow fluff without stamens, (across the) sky broad and earth vast accordingly fly and flutter.

The raucous cries of hundreds of birds in a flock, suddenly see a solitary phoenix.

It scrambles upwards inching (until it) no longer can go up, losing control it abruptly falls a thousand fathoms and more.

Oh, (ever since) I've had two ears, I've never known how to listen to strings or pipes.

But) since I've heard Reverend Ying play, (I've had to) rise from my seat (in respect) to one side.

(I) wave my arm in order to stop him, soaking my robe my tears gush down.

(but) don't cause (your own) ice and coals to go straight to my belly!Some have given these interpretations:

"Floating clouds and willow catkins without roots, drifting freely across the vast expanse of heaven and earth" — this refers to the ‘floating sound,’ characterized by its lightness, neither purely silk nor entirely substantial.

"The cacophony of a hundred birds suddenly reveals the fledgling phoenix" — this indicates the ‘floating sound’ that carries the ‘fingered sound’ within it.

"Climbing and grasping, one must not lose momentum"—this pertains to the ‘continuous sound.’

"A single misstep leads to a precipitous fall"—this signifies the ‘descending sound.’Skilled qin players assert that these sounds are the most challenging to master. The "Duke of Loyal Literature" (here presumably referring to Ouyang Xiu) regarded this poem as akin to (the one by Bai Juyi called) “Listening to the Pipa”. Su Dongpo once composed a “Listening to the Qin” poem, lamenting that Wen Zhong had not been able to see it. However the opinions of these two gentlemen may not tell the whole story.

Qin melodies, ten chapters.

See another volume.

凡琴操各有格,如宮、商、角、徵、羽五調。不轉絃,但宮調則和而且平;商調清亮而韻短;角、徵二調則緩而頗有傷嘆之意;羽調則聲怨,皆得其體。其餘外調,聲韻雖巧,其操弄漸有鄭衛之聲,所謂「為紫亂朱」者是也。

凡彈品,則全與調子不同,要起伏快。今人彈調子,往往如操弄,不知節奏故也。

凡彈調子,如唱慢曲,常於拍前取氣,拍後相接。彈調子者,每一句先兩聲慢續,作數聲,少息,留一聲,接後句,謂之「雙起單殺」。

凡彈操,每句以一字題頭,至盡處,少息,留兩聲,相接後句,與調子相反。學者若能曉此三事,則品、調、曲自能分別也。

凡樂部之曲,鄭衛之人象琴操更而為曲。學琴君子,可先究其曲調,知其令曲之有:慢二、急三、慢四、急七。若慢曲,則其亨、顛、徹、拽,正是琴之節奏:吟、揉、掉、抑,並拍前取氣、鬧裡偷聲。「大曲之中,有攧前、入破、歇拍之類,正與大操弄節奏相似。」

凡琴操、調子,有起奏伏之意:或在一句,或在數句,或在一段,或在一曲。此乃古人憂忿躁急、逼狹,而至於此。

凡節奏者,或是兩字相應,或是兩句、或是兩段前後不同,可高以下應,輕以重應,長以短應,遲以速應。此乃韓退之《聽琴詩》云:

假令用蠲,再有蠲,只得用疊蠲、或雙蠲,以至連蠲;此自少而至多,多而至少者,此節奏之妙用也。

(義)海大師有云:「急若繁星不亂,緩如流水不絕。」

葢琴操中,一句將盡處,先想後句起甚聲,卻留前句末後之聲相接,須是「密處放疎,疎處令密」。

取聲韻意,不可令盡;須留一二分韻,取不盡處便作後句,謂之「意有餘」。

俗云:「食㯙欖者,專一取回味。」悟此,深得古人意旨。

(嘗見草書者,須留默畫,與下字相接。)

凡對按、搯起、打摘,亦有節奏;正是「密處疎,疎處密」之意。

假令用打摘,不可相連,須分作兩聲。葢密處要疎。

末、挑、勾、剔、打、摘,同上字隨前句,下字隨後句。

若是打摘對按掐起挑五,先打,少息、却將摘、掐起、挑五合做一聲。葢挑五是後句聲也。

凡吟、揉,引皆候彈了,將餘聲所之,不可錯亂。學者往往不會使吟,又不候彈了,使用指於絃上來往磨數聲,以為奇特,遂失節奏。凡引上,須是揉了方引上;若引下,則下了自有猱矣。

凡前聲使吟或猱,後聲不可恐重疊;引、掉等聲亦同。

凡彈操弄,先定神思,不可雜想。使輕重高下,一曲之內,添減皆在我,不使並指所役,自然得趣。

(義)海大師云:「岩浮雲之在太虛,因風舒卷,萬態千狀,不失自然之趣。」又韓退之云:

「浮雲柳絮無根蒂,天地濶遠隨飛颺。」到這箇田地方,有古意。

凡操弄之作,各有所因。近時學者往往彈數十曲,其聲一般,全無分別。且如《遊春》、《幽居》二操,聲因而意不同。惡夙(悲風?)一曲,前段乃是舜歌《南風》,取徽外聲,之後方見悲風意。如《離騷》者,為弔屈原而作;《昭君怨》者,想像出塞之時。其聲繁亂重疊處多,直婦人之辭也。《高山》、《綠水》深有林泉之真,此古人命操之本意也。

凡引上不可絲毫過度;若引下,抑下注下却不妨,蓋有後聲相彬。所謂「躋攀分才,不可上失勢,一落千丈強」是也。

凡調絃,先看大概聲之高下,取一條為主,然後次第調之。太急則易斷,太緩則無聲;不急不緩,其聲得中。近時學者掛絃太急,好聲高,意謂聲清,卻取聲不得,無往來之韻,此便是樂器中箏、琶也。

(軫 ⬅︎ 輸 (39306. shu "transfer"; seems to be a mistake")

假令大絃合格(律),以大九按大絃,散挑四句,大絃應在九徽上。

應乃(得)四絃高下,應乃(得)四絃低,只軫四絃就之。

又中十勾大絃,以散挑三應;次以名十,打二應散挑四,不應只三絃,然後大九打二,散挑五應;大九打三,散挑只應;名十打四,散挑七應。

若有未應,只軫未調之絃;不可軫已調了者,十分慢彈,細細推之。

凡云節者,節其繁亂並急,奏其緩慢失度之聲,使其吟猱有起、度、伏、合、節。一曲之中,或三五句自成一小段:

起頭一句,少息,方彈數句,留兩聲,急以後段頭句相接,卻少息。從頭至尾一般節奏,自然緩慢成曲。

近時彈者不知此理,全似打羯鼓,不知盡處,真可笑也!

殊失(義)海大師所謂:「急若繁星不亂,緩如流水不絕」之意。此彈琴之大病也,知音者切宜子細。

或云:

善琴者云:此數聲最難工。

文忠公以為《聽琵琶詩》,東坡嘗作《聽琴詩》,恨文忠不及見。

二公之論,似未必然。

琴操十章。

假如《醉翁吟》:「浪然」兩聲慢;「清圓誰彈響空山,無;」(至此少息)「言惟翁」(此是接下句),他皆倣此。

學琴者識曲之調頭,即能彈品;會唱慢曲,即能彈調子;唱得曲破,即會彈操弄。加以指法,則古人用意處即在目前也。

然不必多學,但少彈一品、二調、一操,以僕之所編法,則精專之一法,與萬法皆同也。默而參之,逵其玄之又玄、妙之又妙,必以僕所言為當耳,幸甚。

「嫟嫟兒女(語),恩愛相爾汝;畫然變軒昇,勇士赴敵場。」

又云:

「喧啾百鳥羣,見此鶵鳳凰。」

(聽琴詩:忽見孤鳳凰。)

真得趣也。

假

令大十打三、名十一對按掐起、先打三,少息,却將

搯起之聲先揉方掐以接後句散桃五相接如一聲此疎處令密也。

劃然變軒昇,勇士赴敵場。

浮雲柳絮無根蒂,天地濶遠隨飛颺。

喧啾百鳥羣,忽見鶵鳳凰。

躋攀分付不可上,失勢一落千丈強。

嗟余有二耳,未省聽絲篁。

自聞穎師彈起,坐在一牀,

推手遽止之,濕衣淚滂滂。

穎乎,爾誠能無以冰炭置我傷(木𠂉昜?)!」

「喧啾百烏羣,忽見鶵鳳凰」者,泛聲中寄指聲也;

「躋攀分寸,不可上吟」者,繹聲也;

「失勢一落千丈強」者,歷聲也。

見別卷。

Return to top