|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| WGQP / ToC / Comparative chart | 首頁 |

南宋浙派古琴概論 Southern Song Zhe-School Guqin General Introduction

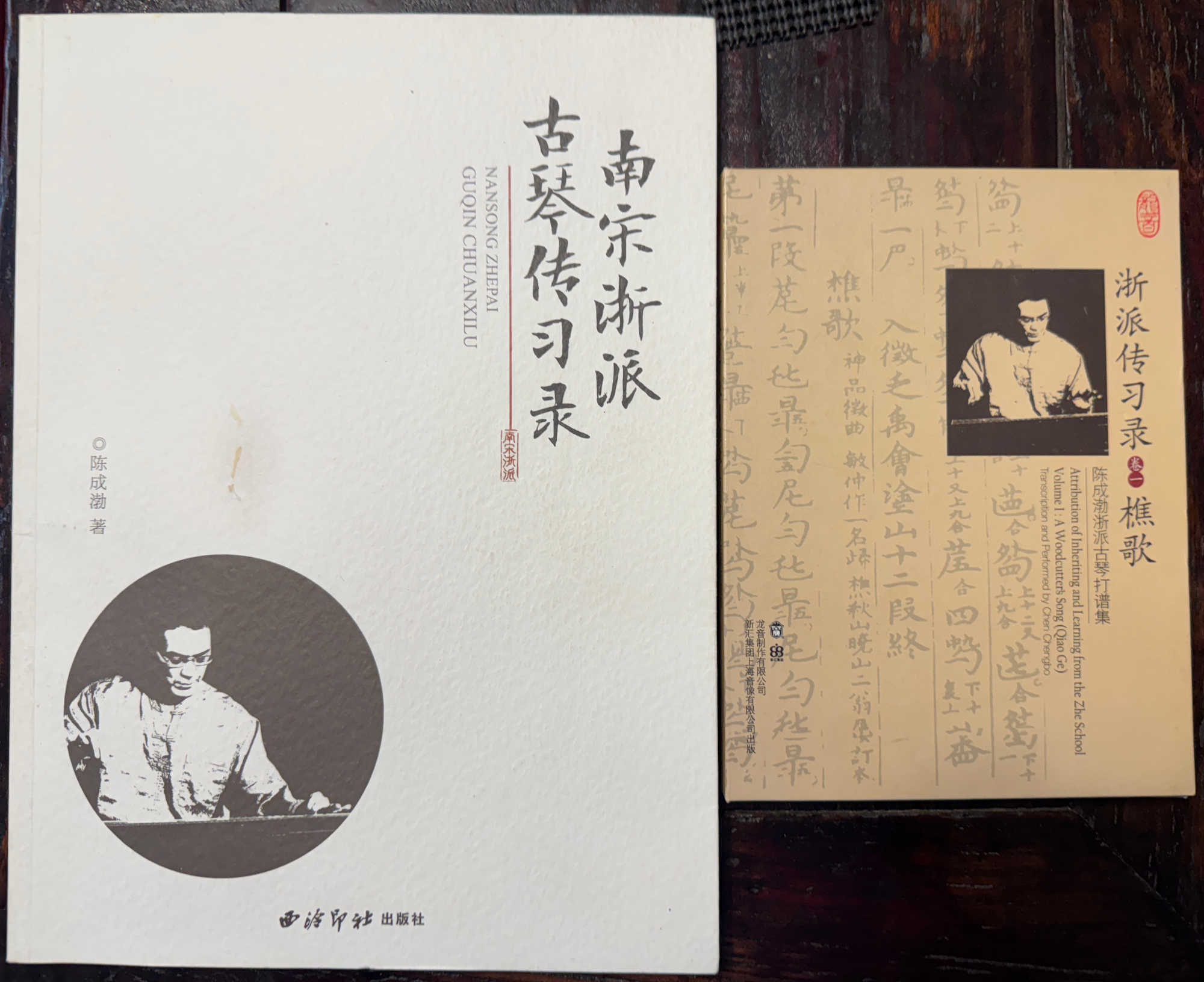

- 陳成渤 Chen Chengbo; see the 看中文 original Chinese text from the CD booklet at right

| I. The Development of Guqin Performance Styles | 陳成渤手冊、光盤 Chen Chengbo Handbook and CD |

The guqin - whether viewed through the legendary account of Emperor Shun “fashioning a qin from paulownia wood and making silk strings for it,” or through such references in the Book of Songs (see Guan Ju) as “Modest is the gentle lady, qin and se she befriend her” — is the most ancient plucked instrument in Chinese history. Over the course of several thousand years of development, generations of qin players continually emerged, and the body of qin-related literature became increasingly complete and abundant. After the invention of jianzipu (simplified tablature) in the Tang dynasty, the recording of qin music became more convenient and comprehensive; from the Ming dynasty onward, more than one hundred different qin manuals were printed. As an instrument, the qin has remained closely aligned with the main currents of Chinese culture over several millennia and has occupied a position of great importance within traditional culture.

From the perspective of performance style, whenever different individuals perform on the guqin, stylistic differences inevitably arise. Tracing this phenomenon back to its earliest historical records, one may look to the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period. In the Zuo Zhuan, “Duke Cheng, Year Nine,” there is an account of the Chu musician Zhong Yi playing the qin. When the Marquis of Jin inspected his army and encountered the captured Zhong Yi, he “had him play the qin, and Zhong Yi performed ‘southern airs’”

From this record it is clear that Zhong Yi’s performance already exhibited a distinct regional character. Such regional style must have been closely connected to local folk song traditions and regional speech patterns (Xu Jian, Introductory History of the Qin).

By the Tang dynasty, the renowned qin master Zhao Yeli described regional styles as follows :

“The sounds of Wu are clear and gentle, like the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, flowing on continuously and unhurriedly, possessing the bearing of a cultivated gentleman; the sounds of Shu are impetuous and urgent, like surging waves and rushing torrents, embodying the brilliance of heroic figures of the age.” (Zhu Changwen, The Qinshi, Song dynasty)

During the Tang dynasty, the qin world also recognized the so-called “Shen-family style” and “Zhu-family style.” According to the History of the Qin, the famous Tang qin master Dong Tinglan “excelled in the tonal styles of both the Shen and Zhu families.” The poet Rong Yu praised Dong Tinglan in verse, writing that “the Shen family and the Zhu family alike are utterly surpassed.”

In the Song dynasty, the qin master Cheng Yujian stated in his Discourse on the Qin: “The capital style is excessively forceful; the Jiangxi style errs in frivolity; only the styles of the Two Zhe regions (eastern and western Zhejiang) are substantial without being rustic, refined without being pedantic.”

From Zhong Yi’s performance of the “southern mode,” through the Tang dynasty’s “Wu sound,” “Shu sound,” “Shen-family style,” and “Zhu-family style,” and on to the Song dynasty’s “Jiangxi” and “Two Zhe” performance styles, these developments all reflect the continuous evolution of the guqin as an instrument. They constitute precisely the formative, preparatory stage in the emergence of distinct guqin schools.

II. The Formation of the Southern Song Zhe-School Guqin Tradition

The formation of guqin schools is not solely the result of broad social and cultural developments and historical momentum. It also requires the presence of several internal conditions: representative figures, clearly identifiable performance styles, continuity of teacher–student transmission, and the inheritance of a coherent score lineage. It was precisely through the convergence of these four conditions that, toward the end of the Southern Song dynasty, the Zhe-school guqin tradition emerged in a timely and organic manner in the history of the guqin, shining forth like a brilliant pearl.

2.1. Representative Figures

郭沔 (ca. before 1190–after 1260), courtesy name Chuowang, was a native of Yongjia in the Southern Song period (present-day Lucheng, Wenzhou). He achieved renown in his own time for his qin artistry. Guo Mei once served as a qingke (resident retainer) in the household of the official Zhang Yan in Lin’an. Zhang Yan, courtesy name Xiaoweng, was a jinshi of the fifth year of the Qiandao reign and rose to the rank of Grand Master of the Palace (Guanglu dafu). A devoted enthusiast of the qin, Zhang Yan invited Guo Chuowang to reside in his household so that they might study the instrument and exchange insights on qin art together.

During this period, Guo Chuowang was exposed to a vast number of court-held “cabinet scores” (gepu) from Zhang Yan’s official collection, as well as to “wild scores” (yepu) circulating among the populace. This greatly broadened his horizons, and his qin artistry steadily matured and refined. Ultimately, he distinguished himself as a master of his generation and became the founder of the Zhe-school lineage. Guo Chuowang’s extant compositions include Xiao Xiang Shui Yun (Mists and Clouds over the Xiao and Xiang Rivers), Fan Canglang (Drifting on the Canglang Waters), and Qiu Hong (Autumn Geese). 杨缵, courtesy name Siweng, sobriquet Shouzhai (also known as Zixia), was a native of Qiantang and rose to the position of Minister of Agriculture (Sinong qing). According to the Qidong Yeyu, he was fond of antiquity, broadly learned, and especially proficient in qin theory and pitch regulation, with the ability to compose music according to modal structures. Yang Zuan frequently exchanged insights on qin art with his retainers, the qin masters Mao Minzhong and Xu Tianmin.

In his later years, Yang Zuan brought together the transmitted scores of Guo Mei that he had studied over many years and a large number of pieces collected from popular circulation. He compiled them into the Zixia Dongpu in thirteen juan, recording a total of 486 pieces. This work, now lost, was the first large-scale, comprehensive guqin score anthology in history and was known among contemporaries as the “Zhe Scores” (Zhepu). 徐宇, courtesy name Tianmin, sobriquets Xuejiang and Piaoweng, studied under Liu Zhifang, a disciple of Guo Chuowang. He was highly accomplished in qin performance and renowned in his time. Together with Mao Minzhong, he served as a retainer in Yang Zuan’s household and participated in the compilation of qin scores. Among the pieces attributed to him and transmitted to later generations is Zepan Yin (Intoning by the Marsh Bank).

Xu Tianmin established the “Xu lineage of the Zhe school” that flourished during the Yuan and Ming periods. The guqin was transmitted within the Xu family across generations, and over the course of several centuries this familial transmission enabled the Southern Song Zhe-school tradition to prosper and develop.

毛逊, courtesy name Minzhong, was a native of Quzhou in Zhejiang. He initially studied the “Jiangxi scores” and later turned to the “Guo (Chuowang) scores,” refining his technique to a high level of purity. His compositions include Yuge (The Fisherman’s Song), Qiaoge (The Woodcutter’s Song), Peilan, Shanju Yin (Intoning in Mountain Dwelling), and Zhuang Zhou Mengdie (Zhuang Zhou Dreams of Becoming a Butterfly). Together with Xu Tianmin, he served as a retainer under Yang Zuan, devoting himself to intensive study of qin performance and score compilation. Mao Xun’s creative output greatly enriched the repertoire of the Southern Song Zhe-school and made a substantial contribution to its development.

2.2. Performance Style of the Zhe School

The Southern Song Zhe-school guqin tradition originated in the Southern Song, developed and was transmitted during the Yuan dynasty, and flourished in the Ming dynasty. The emergence of the school itself was founded on the inheritance of earlier performance achievements. Over several subsequent centuries, successive generations of qin masters appeared, collectively forming a distinctive performance style. Its characteristics may be summarized as follows.

In his Discourse on the Qin, Cheng Yujian of the Song dynasty commented on regional qin styles of his time: “The capital style is excessively forceful; the Jiangxi style errs in frivolity; only the styles of the Two Zhe regions are substantial without being rustic, refined without being pedantic.” The Jiang school of that period placed greater emphasis on vocalization, such that every press and pluck corresponded closely to song lyrics. By contrast, the Zhe school emphasized the expressive function of the instrument itself. As stated in the Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi: “The qin was established in the age of Fuxi; it had sound but no text. Later generations explained it with words—this was misguided. We respectfully follow the ancient saying and remove the text in order to preserve the plucking and striking.”

Among extant Ming-dynasty Zhe-school scores, of the twenty-nine pieces collected in the Wugang Qinpu, only one—Guiqulai Ci—is a qin song. Among the seventy-two pieces recorded in the Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, none are qin songs.

(B.) Regulated and purified fingering techniques

After the invention of abbreviated tablature in the Tang dynasty, right-hand techniques at one time became increasingly complex. In certain early pieces preserved in Shenqi Mipu, such as those in the section “Taigu Shenpin,” right-hand techniques like que zhuan (“reverse turn”) and quan qian (“full pull”) appear; these techniques are rarely encountered in Zhe-school scores. The use of the ring finger for da (strike) and zhai (pluck) is also greatly reduced.

This reflects the Zhe-school emphasis on instrumental expression, whereby all fingering techniques are subordinated to musical imagery. Consequently, later developments in technique placed greater emphasis on rationality and expressive clarity. Liu Zhu of the Ming dynasty wrote in Sitong Pian: “The sound of the Jiang style is mostly intricate and fussy; the Zhe style is mostly relaxed and flowing, and is even clearer and more transcendent than the Jiang style.” The Ming Zhe-school score Wenhuitang Qinpu likewise characterizes the Zhe-school style as “clean and precise.” The Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi includes a poem titled “Introduction to Qin Playing,” attributed to Xu Mengji. The poem reads:

“When the sound is complete, extended notes must emerge from distance;

When the tone ceases, flying吟 is only then employed.

One must seek marvel by playing as though breaking the string;

Pressing that renders the listener wooden is what is called wondrous.

Lightness and heaviness, speed and slowness must respond together;

Colliding, rubbing, and moving must avoid strangeness and disorder.

If one can silently apprehend the intent within,

Though the meaning be deep, it may be fully understood.”

Xu Mengji was a major figure of the Xu lineage of the Zhe school. By including this poem, the compiler emphasized both the orthodox transmission of the score and the core principles of qin performance. The poem vividly reflects the rigor of Southern Song Zhe-school technique and offers valuable reference for the study of its fingering practices.

(C.) Large-scale composition of qin pieces

Among the twenty-nine pieces recorded in the Wugang Qinpu, twelve are large-scale works of ten sections or more. These include pieces of ten sections (Meihua Yin, Yuge, Qingdu Yin, Heming Jiugao, Xiao Xiang), eleven sections (Yilan, Qiaoge), twelve sections (Yu Hui Tushan), thirteen sections (Yangchun, Zhi Chao Fei, Peilan), and thirty-five sections (Qiuhong). Fourteen are medium-scale works of six to nine sections, and three are small works of three sections.

In fact, pieces such as Changqing, Zhuang Zhou Mengdie, and Wu Ye Ti are technically demanding and exceed nine minutes in performance duration. From this perspective, more than half of the repertoire recorded in the Wugang Qinpu consists of large-scale compositions.

(D.) Rich compositional techniques and flexible methods

In pieces such as Peilan in the Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, written in the yu mode, the composer employs the seven-tone yayue scale “6–7–1–2–3–#4–5–6,” with frequent use of altered tones. These features represent a living fossil of traditional Chinese pitch theory. In pieces such as Xiao Xiang Shui Yun, Qiaoge, and Baixue, altered tones appear frequently. In Baixue, for example, the altered tone #4 is repeatedly employed before quickly returning to 5; the use of the harmonic #4 enhances the imagery of swirling, crystalline snowflakes.

The application of such techniques enriches the musical palette and powerfully supports the expression of specific emotional content. In later qin theory, many of these altered tones were subsumed into the five-tone framework, resulting in a gradual loss of certain original sonic qualities—an outcome much to be regretted.

(E.) A rich and well-developed performance repertoire system

Zhe-school score compilation was pragmatic and emphasized musical expressivity, avoiding empty or sycophantic works included merely to flatter contemporary tastes. Based on the Wugang Qinpu and Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, the repertoire may be categorized into four types:

Confucian themes: Yilan, Yasheng, Wenwang, etc.

Daoist themes: Liezi Yufeng, Zhuang Zhou Mengdie, etc.

Landscape and scene-painting: He Wu Dongtian, Qiaoge, Yuge, Meihua Yin, Yangchun, Baixue, Changqing, Ainai, Xiao Xiang Shui Yun, etc.

Historical and literary figures: Gu Jiao Xing, Chu Ge, Zhaojun Yin, Qu Yuan Wen Du, Li Sao, Guiqulai Ci, etc.

Among the three representative Ming Zhe-school scores—Wufeng Qinpu, Qinpu Zhengchuan, and Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi—the first two contain largely identical repertoires. The compiler of the Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, Xiao Luan, emphasized the principle that “each piece must be preceded by an intoning.” Accordingly, each major piece is prefaced with a short piece of similar style, such as Chonghe Yin (paired with Yangchun), Gufang Yin (paired with Meihua Sannong), Sigui Yin (paired with Yilan), and Shanju Yin (paired with Qiaoge), thereby enriching the performance repertoire.

2.3. Continuity of Transmission (Teacher–Student Lineage)

From its founding by 郭楚望, the Southern Song Zhe-school guqin tradition maintained a notably regulated and rigorous system of transmission.

(Insert chart)

Based on historical records, the principal lineage of transmission within the Southern Song Zhe-school may be outlined as follows:

郭楚望 → 刘志方 → 毛敏仲, 徐天民, 杨缵 → 徐秋山, 袁桷, 金如砺 → 徐梦吉, 宋尹文 → 徐和仲 → 徐惟谦 → 张助 → 戴义 → 黄献, 萧鸾, and others.

Within this lineage, every qin master occupies a position of considerable importance in the history of the guqin. Moreover, one can clearly discern the distinctive pattern of familial transmission within the Xu lineage: Xu Tianmin → Xu Qiushan → Xu Mengji → Xu Hezhong → Xu Weiqian. This multigenerational inheritance within a single family played a decisive role in sustaining and consolidating the Zhe-school tradition. The Xingzhuang Taiyin Xupu records the following description: “Remote yet resonant among forested ravines, subtle yet heard beyond the balustrades; the pieces transmitted are all called ‘Xu-school’ works.” In the Ming dynasty, Liu Zhu wrote in Sitong Pian: “Among those who practice Min-style playing, scarcely one or two in a hundred; among those who practice Jiang-style playing, perhaps three or four in ten; among those who practice Zhe-style playing, six or seven in ten.” From the Yuan dynasty through the Ming dynasty, over the course of several centuries, the Xu family assumed a major historical responsibility in the transmission and development of Zhe-school qin art. Through the combined efforts of the Xu lineage and successive generations of other qin masters, the Southern Song Zhe-school once dominated the qin world, becoming a central force shaping guqin aesthetics during the Yuan and Ming periods and exerting a profound influence on later qin scholarship and performance.

2.4. Score Lineage and Transmission

From the early Song dynasty onward, qin scores came to be divided into two broad categories: court-produced “cabinet scores” (gepu), intended for imperial use, and privately transmitted “wild scores” (yepu) circulating among the populace. During the Southern Song, the official Zhang Yan—who rose to the rank of Grand Master of the Palace—was an ardent devotee of the qin. He collected large numbers of both court-held cabinet scores and privately circulated wild scores, compiling them into the Qincao Pu in fifteen juan and the Diaopu in four juan (neither of which survives today).

While serving as a resident retainer in Zhang Yan’s household, 郭楚望 assisted in the organization and study of these materials. Through extensive exposure to diverse score traditions, he absorbed the essential elements of earlier qin repertories, broadened his artistic vision, and ultimately cultivated the foundations of the Southern Song Zhe-school tradition, becoming its acknowledged founding master.

In the organization and transmission of Zhe-school qin scores, 杨缵 made an indelible contribution. As noted above, he arranged for 徐天民 to study under Liu Zhifang in order to learn the transmitted repertoire of Guo Chuowang. In his later years, Yang Zuan gathered a large number of scores and compiled them into the Zixia Dongpu in thirteen juan (now lost), recording 486 pieces. This anthology, known at the time as the “Zhe Scores,” replaced the widely circulated “Jiangxi Scores” as the dominant repertory tradition. The appearance of this anthology and the wide circulation of its contents laid a solid foundation for the rise of the Southern Song Zhe-school guqin tradition.

According to Jiao Hong’s Guoshi Jingji Zhi, Xu Tianmin authored the Xu Men Qinpu in ten juan (now lost). Xu Tianmin’s disciple 金如砺 was highly accomplished in qin studies. The Biographies of Qin Masters through the Ages records of him: “He fully grasped the subtlety of Master Xu, and was further able to probe mysteriously into those meanings beyond the score not transmitted by the Lesser Master.” Jin Ruli arranged the pieces transmitted by Xu Tianmin according to the five tones, assigning one mode, one intent, and one cao to each, for a total of fifteen pieces, and compiled them into the Xiawai Qinpu (now lost), one of the representative Zhe-school score collections.

With the generation of 徐和仲, the Zhe-school tradition flourished greatly. Xu Hezhong’s qin artistry was described as “effortless in execution, with interest arising naturally from within.” He compiled the Meixuewo Shanrun Qinpu (now lost).

黄献, courtesy name Shenxian, sobriquet Wugang, entered the palace at the age of eleven and studied under the palace qin master Dai Yi. Huang Xian described his own practice as “unceasing diligence from morning to night, without pause even for a moment.” In 1546 he compiled and printed the Wugang Qinpu. This is the earliest extant Ming-dynasty qin score explicitly identified as the “orthodox transmission of the Xu lineage of the Zhe school,” and it constitutes a highly valuable reference for the study of Southern Song Zhe-school guqin art.

A contemporary of Huang Xian, 萧鸾, courtesy name Xingzhuang, was a native of Yangwu. He studied the qin from childhood and devoted himself to intensive study of the Southern Song Zhe-school tradition, remaining inseparable from it for over fifty years. In 1557, he compiled the Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, in three juan, containing seventy-two pieces. Around the same period, Yang Jiasen compiled the Qinpu Zhengchuan (ca. 1561), whose contents largely correspond to those of the Wugang Qinpu.

In 1596, the Qiantang native Hu Wenhui compiled the Wenhuitang Qinpu in six juan. The first three juan consist of essays on qin theory, while the latter three record sixty-nine pieces described as “Zhe-style pieces personally transmitted.” The preface states: “The scores I possess are all personally transmitted Zhe-style pieces, never yet printed; those with discerning eyes will recognize their secret nature.” This statement emphasizes the manual’s claim to preserve an unprinted, esoteric Zhe-school tradition.

Based on the historical records and extant qin scores, it is evident that Zhe-school score transmission continued uninterrupted through the Ming dynasty. The sustained inheritance of score traditions was one of the principal reasons the Southern Song Zhe-school guqin tradition was able to flourish and spread over the course of several centuries.

III. The Influence of the Southern Song Zhe School on Later Qin Traditions

3.1. Systematic Consolidation of Earlier Repertoires

After the invention of abbreviated qin tablature (jianzipu) by qin masters such as Cao Rou in the Tang dynasty, the recording of qin music became considerably more convenient. As a result, the number of notated pieces increased, and the body of transmitted repertory in different regions came to include both fine and inferior materials. By the Song dynasty, official court collections (“cabinet scores,” gepu) and privately transmitted scores (“wild scores,” yepu) had reached an enormous scale. From Guo Chuowang’s work in assisting Zhang Yan with the organization of the Qincao Pu, and from the formation of Guo’s own distinctive performance and transmission tradition (“Guo scores,” Guopu), through the subsequent transmission by his disciple Liu Zhifang to Xu Tianmin, and onward into Yang Zuan’s compilation of the Zixia Dong Qinpu, later Zhe-school qin masters continued this process of repertory organization in such works as the Xu Men Qinpu and the Xiawai Qinpu. Although these earlier anthologies are now lost, the scale of their contents and their principles of classification, as recorded in bibliographic and historical sources, indicate a sustained project of standardizing and professionalizing earlier qin repertories—an undertaking of clear significance for the healthy development of guqin culture.

Moreover, extant manuals such as the Wugang Qinpu, Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, and Wenhuitang Qinpu preserve many celebrated pieces associated with the Zhe tradition across successive eras. They therefore constitute precious resources for the study of guqin music and traditional culture.

3.2. Regulation and Systematization of Qin Performance Techniques, and the Strengthening of the Qin’s Solo Instrumental Function

Within the Southern Song Zhe-school tradition, the regulation and systematization of qin performance techniques constituted a major contribution to later qin studies. Judging from extant transmitted scores such as the Wugang Qinpu and the Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, Zhe-school fingering notation is comparatively standardized, pragmatic, and precise. In right-hand technique, the use of the ring finger for da (striking) and zhai (plucking) had largely fallen into disuse. Many of the complex right-hand techniques found in earlier traditions—such as que zhuan (“reverse turn”), quan qian (“full pull”), song lun (“sending roll”), and huan qi zhuan (“slow-rise turn”)—were essentially abandoned. Likewise, among the various forms of “locking” techniques (suo), such as “large,” “small,” “short,” “long,” “finger-changing locks,” and “back locks,” only four types—long lock, short lock, back lock, and small lock—appear in the Wufeng Qinpu.

Left-hand techniques also show a restrained and purposeful approach. The categories of yin (vibrato) and nao (wobble) are relatively limited in number. In the Wugang Qinpu, yin is divided into three types: retreating yin, moving yin, and stopped yin. Among nao techniques, zhuang (percussive wobble) predominates. Sliding tones and vibrato techniques occupy a higher proportion of musical material than in other contemporaneous score traditions, and they are frequently combined with techniques such as dai shang (“carrying upward”) and huan zhi (“finger change”). This reflects the Zhe school’s emphasis on left-hand resonance techniques and illustrates the historical shift in qin music from an earlier condition of “many notes, few resonances” toward one of “fewer notes, richer resonance.”

The Southern Song Zhe-school aesthetic advocated the principle of “removing text to preserve plucking,” favoring a purely instrumental musical ideal. This aesthetic stance directly countered the lyric-dominated, ornate, and lightweight tendencies of the contemporaneous Jiang school, which emphasized matching musical gestures to textual phrasing. By redirecting attention to instrumental technique and musical structure, the Zhe school made a substantial contribution to the technical development of the qin as a solo instrument.

A later assessment by the Qing-dynasty Zhe-school qin master 高濂 offers a critical perspective on departures from this tradition:

“People today do not investigate meaning, do not seek enlightened teachers, do not study score methods, and do not refine hand techniques. As a result, the inflections of sound and the methods of tone production lose proper balance; tempo and articulation become inappropriate; rise and fall lack regulation. They know sound but not tone, move their fingers but not their intent—what then is the value of playing? Some pursue florid cleverness and frantic speed, flaunting novelty and exaggeration without seeking proper method. Within correct standards there lies the marvel of spacious ease and lingering resonance; yet their playing disperses open-string sounds like a konghou, snatches connected tones like a zither or ruan, and thus gravely loses refined sound—how laughable indeed.”This critique underscores the Zhe-school emphasis on disciplined technique, intentionality, and refined instrumental expression, and it highlights the enduring influence of Southern Song Zhe-school principles on later evaluations of qin performance practice.

3.3 The Zhe School’s Role in Promoting and Influencing the Formation of Other Qin Schools

The Qing-dynasty scholar Jiang Wenxun, in his Essential Remarks on Qin Studies, discussed the formation of qin schools as follows:

“Among the schools transmitted in the world today, most take the Wu school as their model; even those of Shu origin now follow the Wu school. The Wu school later divided into two branches: the Yushan school and the Guangling school. The Yushan school arose during the reign of the Wanli Emperor of the Ming dynasty, when Master Yan Tianchi of Changshu, at a time when qin studies had declined, rejected vulgarity and returned to elegance, serving as a central pillar of the art. Residing at Mount Yu, he was widely revered by discerning listeners of his time and thus became the founder of the Yushan school. People compared him to Han Yu in classical prose and to Zhang Zhongjing in medicine… Tianchi’s qin learning came from Chen Xingyuan… Xingyuan’s honored father, Chen Aitong, was foremost among qin masters of his age. Aitong transmitted his art to Zhang Weichuan, who transmitted it to Xu Qingshan, who transmitted it to Xia Yujian. At that time, notable figures included Shi Aipan, Shen Taishao, Ge Zhuangyue, Zhao Yunsuo, Gu Yunqiao, and Lu Jiulai.”

Liu Chenghua, in his article The Lineage of the Southern Song Zhe School’s Influence on Later Qin Schools, observes that the “Wu school” referred to by Jiang Wenxun is in fact a residual branch of the Zhe school. During that period, many disciples of the Xu lineage were serving as officials or lecturers in the Suzhou region. For example, 徐梦吉, grandson of Xu Tianmin, taught in Changshu, and the eminent Xu-lineage disciple 张助 was active in Suzhou. Consequently, the so-called “Wu school” should be understood as the Zhe school transplanted to the Wu region, that is, a regional continuation of the Xu lineage.

At the same time, another tradition did exist in the Wu region, namely the Jiang school, commonly characterized by the saying “Zhe performance follows the Xu lineage; Jiang performance follows the Liu lineage.” This Jiang school was centered primarily in Songjiang (present-day Shanghai). However, its stylistic orientation differed markedly from that of the later Yushan school. Whereas the Yushan school emphasized clarity, harmony, restraint, and distance, the Jiang school was described as “intricate and overly elaborate.” Since the Yushan school traced its authority to the Wu school but did not share the stylistic traits of the Jiang school, the Wu school upon which it drew must therefore have been the Zhe school.

From this perspective, the origins of both the Yushan and Guangling schools, insofar as they derive from the Wu school, ultimately trace back to the Zhe school. Jiang Wenxun further notes that the founding figure of the Yushan school, Yan Cheng (sobriquet Tianchi), drew upon four principal sources in his qin learning:

- the influence of the Xu lineage, since Xu Mengji, father of Xu Hezhong, taught in Changshu and thereby transmitted Xu-lineage qin learning to the region;

- study with Chen Xingyuan, son of the eminent qin master Chen Aitong, who himself was a second-generation disciple within the Xu lineage;

- study with an otherwise obscure woodcutter, whom Yan Tianchi referred to as “Xu Yixian”; and

- the absorption of strengths from the renowned capital-region qin master Shen Yin (courtesy name Taishao), who was also a Zhe-school musician, in order to remedy his own deficiencies.

The qin master 查阜西 repeatedly emphasized that “the Yushan school is in fact the later embodiment of the Zhe school.” The Ming-dynasty theorist Liu Zhu similarly observed in Sitong Pian: “The Jiang style is mostly intricate and fussy; the Zhe style is mostly open and flowing, and is thereby clearer and more transcendent.” Yan Tianchi absorbed this Zhe-school ideal of clarity and transcendence, integrating it with his own cultivation and artistry to reform the chaotic and superficial qin styles prevalent in his time. In doing so, he established the Yushan school’s distinctive aesthetic of “clarity, subtlety, restraint, and distance,” exerting a profound influence on later qin studies.

Jiang Wenxun further wrote of the Guangling school:

“The Guangling school arose with Master Xu Ergong of Yangzhou in the early Qing. His son Jinchen transmitted the family learning and had it engraved in the Xiangshantang Qinpu. Later, Nian Yungong engraved the Chengjiantang Qinpu. Their stylistic character is akin to that of the Shu school.”

Given the geographical proximity of Yangzhou and Guangling and the frequent interactions among qin players in the region, mutual stylistic influence was only natural.

In the second year of the Guangxu reign (1876), Tang Mingyi, Ye Jiefu, and Zhang Kongshan jointly published the Shu-school Tianwenge Qinpu. 张孔山, sobriquet Buranzi, was the most important representative of the Shu school. Notably, he was a native of Zhejiang and had studied qin with the Zhe-school master Feng Tongyun before later becoming a Daoist at Mount Qingcheng. The pieces he transmitted, such as the seventy-two-rolling-strum version of Flowing Water, continue to circulate widely in the qin world today.

From the Ming and Qing dynasties onward, the Yushan and Guangling schools served as points of origin for many later traditions, including the Jinling, Zhucheng, Lingnan, Jiuyi, Pucheng, and Mei’an schools. Through mutual influence and synthesis, these schools each developed distinctive characteristics and collectively advanced the technical and stylistic development of guqin performance. Tracing their origins back to the Zhe school, one may say that the transmission of Zhe-school qin learning was broad in scope and deep in influence.

IV. The Decline of the Southern Song Zhe-School Guqin Tradition

Judging from the foregoing discussion of teacher–student transmission and score-lineage inheritance, after its establishment by 郭楚望 in the late Southern Song, the Zhe-school guqin tradition achieved early prominence through the collective efforts of Liu Zhifang, Mao Minzhong, Xu Tianmin, Yang Zuan, and other Zhe-school qin masters. During the Yuan dynasty, prominent qin figures such as 袁桷, 金如砺, and He Juji all studied qin under Xu Tianmin and attained notable accomplishments.

Yuan Jue authored the well-known Qin Shu (Treatise on the Qin), which discusses the evolution of score traditions from the decline of official court “cabinet scores” to the rise of privately transmitted “Jiangxi scores,” and the subsequent replacement of these by the Song–Yuan “Zhe scores.” This work provides concrete historical documentation for the formation of the Zhe-school tradition and possesses high scholarly value for the study of qin history. Jin Ruli, a Daoist of the Kaiyuan Monastery in Hangzhou, was highly accomplished in qin performance. The Biographies of Qin Masters through the Ages evaluates him as follows: “He fully grasped the subtlety of Master Xu and was further able to probe mysteriously into those meanings beyond the score not transmitted by the Lesser Master.” He compiled the Xiawai Qinpu, which became one of the representative score collections of the Zhe school.

The emergence of Zhe-school qin masters and qin manuals during the Yuan dynasty exerted a powerful impetus for the further development of the tradition. As for the Ming dynasty, Liu Zhu famously wrote in Sitong Pian: “From those in court offices above to those dwelling in forests and mountains below, instruction is passed on in succession, and all follow this tradition. Among qin masters, when one meets another and asks which score he studies, none fail to reply: the Xu lineage.” From such descriptions, it is clear that the fervor with which people studied the “Xu lineage” at that time was in no way inferior to the enthusiasm with which people today admire popular singing celebrities (Xu Jian, The Rise and Transformation of the Two-Zhe Qin School).

In the late Ming and early Qing periods, Zhe-school qin masters gradually dispersed into the Wu and Changshu regions. With the rise of the Yushan and Guangling schools, the Zhe school gradually declined, eventually surviving only in written accounts, without living practitioners or sustained transmission. After flourishing for a time, the Southern Song Zhe school withdrew from the historical stage.

Viewed against the broader history of the guqin and the evolution of the Southern Song Zhe school, its decline and eventual disappearance after the Ming dynasty resulted from both historical circumstances and internal factors, chief among them the rupture of teacher–student transmission. From Guo Chuowang through to Ming-dynasty figures such as Huang Xian and Xiao Luan, the Zhe school maintained a clearly articulated and orderly lineage over the course of ten generations. The vigorous development of Zhe-school qin art during this period is evident in surviving manuals: the Wugang Qinpu, Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, and Qinpu Zhengchuan contain largely identical versions of pieces with the same titles, demonstrating the rigor of their transmission.

However, in the slightly later Wenhuitang Qinpu, noticeable changes appear in pieces bearing the same titles. For example, in Meihua Sannong, the two harmonic phrases “1–5–5–5” in the thematic section are unconnected in the Wugang Qinpu and related manuals, whereas in the Wenhuitang Qinpu they are linked by the connecting tones “3–2.” In the fifth section of Qiaoge, the earlier manuals prescribe kneeling the left-hand ring finger at the fifth hui on the seventh string, whereas in the Wenhuitang Qinpu this fingering is eliminated and replaced by pressing with the left-hand thumb, accompanied by melodic alteration.

Although the compiler of the Wenhuitang Qinpu, Hu Wenhui, claimed that “the scores I possess are all personally transmitted Zhe-style pieces,” the manual does not clearly document Hu’s own teacher–student lineage. Judging from the musical content of the score, it differs to a certain extent from other Zhe-school transmission manuals. It may therefore provisionally be regarded as a collateral branch derived from the Southern Song Zhe-school tradition.

By the ninth year of the Qianlong reign (1744), Su Jing and others in Qiantang jointly compiled the Chuncaotang Qinpu. Because its compilers were natives of Qiantang (Hangzhou), this manual was later referred to as a Zhe-school transmission score. However, upon examining pieces such as Peilan, Yilan, and Meihua Sannong, the author finds that they differ substantially from Ming-dynasty Zhe-school transmission versions and no longer represent the Zhe school in its original sense.

Thus, after figures such as Huang Xian and Xiao Luan in the Ming dynasty, the true lineage of the Southern Song Zhe school had in fact already been broken. Although score books continued to circulate, the absence of oral instruction and experiential transmission inevitably hindered the tradition’s propagation and development.

The restrictive political and cultural environment of the Qing dynasty led qin practitioners to place greater emphasis on the qin’s function as a vehicle of moral orthodoxy. Left-hand vibrato and sliding techniques were extensively developed, while the Yushan school’s aesthetic of “clarity, subtlety, restraint, and distance” came to be widely revered. At the same time, the Songxianguan Qinpu of the Yushan school excluded faster-tempo pieces such as Xiao Xiang Shui Yun and Wu Ye Ti, thereby to some extent neglecting the instrument’s multifaceted expressive potential. In this respect, later Qing practice diverged from the Zhe school’s original emphasis on instrumental expressivity.

After the Ming-dynasty figures Huang Xian and Xiao Luan, no clearly defined Zhe-school transmission lineage survived. Nevertheless, qin masters native to the Zhe region continued to appear, including Qiantang musicians such as Su Jing and Dai Yuan, who participated in compiling the Wenhuitang Qinpu, as well as Zhu Haihe (Daoist name Longqiu), a qin master and qin maker from Longyou; Gao Teng of Xitang; Wu Jinling of Longquan; and Yan Diaoyu of Yuhang. However, none of these figures maintained a direct teacher–student relationship with the Southern Song Zhe school or the Xu-lineage transmission.

Later generations referred to such musicians as “Zhe-school qin masters,” but this designation was purely geographical in nature. As for Qing-dynasty Qiantang qin masters such as Chen Dabin (sobriquet Taixi), Lu Yaohua, and Yu Qian (sobriquet Qiaogu), they placed greater emphasis on qin songs and were even further removed from the stylistic character of the Southern Song Zhe school.

Xu Jian, in The Rise and Transformation of the Two-Zhe Qin School, wrote: “The Two-Zhe qin school began in the Song, flourished in the Ming, transformed in the Qing, and occupies a pivotal position in the history of the qin.” Based on the analysis presented here, however, the decisive factor in the school’s decline was the rupture of teacher–student transmission in the late Ming period. Accordingly, the Southern Song Zhe school may be said to have originated in the Song, flourished in the Yuan and Ming, and declined in the late Ming. If the Qing dynasty is said to have possessed a “Zhe school” or “new Zhe school,” this designation refers only to a regional concept and bears no substantive transmission relationship to the Southern Song Zhe school.

After the Zhe-school guqin tradition declined at the end of the Ming dynasty, its artistic essence did not vanish. Rather, having fulfilled its historical role over several centuries, it transmitted its nourishment and refined elements into other regional qin traditions. As a result, numerous schools with distinct characteristics emerged across different regions, contending and flourishing together. There can be no doubt that the Southern Song Zhe school exerted an immense influence on the subsequent development of qin schools.

Clarifying notes

Clarifying Notes (Section I)

1. “Southern mode” (南音) This refers not to a specific composition but to a regional musical idiom associated with the southern states, particularly Chu. In early sources it signals regional character rather than modal theory in the later technical sense.

2. Wu (吴) and Shu (蜀) sounds These are regional stylistic designations rather than formal schools. “Wu” broadly refers to the Jiangnan region, while “Shu” refers to Sichuan. The contrast emphasizes gentleness versus urgency, refinement versus intensity.

3. “Shen-family” and “Zhu-family” styles (沈家声、祝家声) These were performance traditions associated with particular master lineages in the Tang dynasty, reflecting early forms of stylistic lineage before fully developed “schools” (派) emerged.

4. “Two Zhe” (两浙) Refers to the Eastern and Western Zhejiang regions as an administrative and cultural unit. In later discourse, “Two Zhe” becomes synonymous with what is eventually termed the Zhe school (浙派).

5. Preparatory stage of school formation The text emphasizes that these early stylistic distinctions represent incipient developments—regional and lineage-based tendencies that precede the fully articulated schools of the Southern Song and later periods.

Clarifying Notes (Section II, [parts 1 and 2])

1. “Cabinet scores” (gepu) and “wild scores” (yepu)

These terms distinguish court-maintained collections from unofficial, privately transmitted scores circulating among musicians.

2. Instrument-centered aesthetics

The Zhe school’s emphasis on “removing text to preserve plucking” reflects a conscious rejection of lyric-dominated performance in favor of purely instrumental expression.

3. Altered tones (偏音)

These refer to pitches outside the basic pentatonic framework. Their systematic use preserves earlier modal practices later simplified in Ming and Qing theory.

Large-scale sectional form

4. The prominence of long, multi-sectional works reflects both technical confidence and an expanded conception of instrumental narrative. When you’re ready, we can proceed to Section Three: Transmission Lineages, or pause to normalize tran

Clarifying Notes (Section II, Part 3

1. Lineage as authority

In traditional qin culture, the legitimacy of a style depended heavily on clearly articulated teacher–student transmission. The careful enumeration of lineage here serves to establish doctrinal and stylistic continuity rather than mere historical chronology.

2.Familial transmission within the Xu lineage

The Xu family represents one of the clearest examples of long-term hereditary transmission in guqin history, comparable in importance to later familial traditions in other schools.

3. Quantitative claims in Ming sources

Liu Zhu’s numerical comparison of Jiang, Min, and Zhe styles is rhetorical rather than statistical, but it reflects the perceived dominance of Zhe-school practice during the Ming dynasty.

4. “Xu-school” as a synonym for Zhe-school

By the Yuan–Ming period, “Xu school” (徐门) had effectively become synonymous with the orthodox Zhe-school tradition, underscoring the centrality of the Xu lineage in defining the school’s identity.

Clarifying Notes (Section II, Part 4)

1. Loss of early anthologies

Many foundational Zhe-school score collections (Zixia Dongpu, Xu Men Qinpu, Xiawai Qinpu, Meixuewo Shanrun Qinpu) are now lost. Their importance must be reconstructed indirectly through bibliographic records and later extant manuals.

2. Replacement of the Jiangxi tradition

The rise of the “Zhe Scores” reflects not merely stylistic preference but a large-scale reorganization of repertory authority within qin culture.

3. Orthodoxy claims in Ming manuals

Statements emphasizing “personal transmission” and “unprinted secrecy” should be read as assertions of lineage legitimacy rather than literal claims of exclusivity.

4. Continuity through print culture

The survival of the Zhe-school tradition into the Ming period owes much to the transition from manuscript transmission to woodblock printing, which stabilized repertories while still preserving lineage claims.

Clarifying Notes (Section 3.1)

1. “Good and inferior materials” (良莠不齐)

A conventional evaluative phrase indicating uneven quality in transmission; here it frames the need for editorial consolidation.

2. “Standardizing and professionalizing”

The article treats large-scale anthology-making and classificatory organization as a hallmark of mature qin scholarship, not merely repertory collecting.

3. “Guo scores” (郭谱)

This is best understood as a transmission tradition associated with Guo Chuowang’s repertory and style, rather than a single fixed printed manual.

Clarifying Notes (Section 3.2)

1. Reduction of right-hand techniques

The apparent “simplification” of fingering reflects not technical impoverishment but a deliberate aesthetic choice privileging clarity, resonance, and expressive efficiency.

2. “Many notes, few resonances” vs. “few notes, rich resonance”

This formulation captures a major historical shift in qin aesthetics, with the Zhe school playing a key role in foregrounding left-hand expressive techniques.

3. Anti-lyric instrumental stance

The Zhe-school rejection of lyric-driven performance marks a decisive moment in the emergence of the qin as an autonomous instrumental art rather than a song-accompaniment medium.

4. Later critical reception

Gao Lian’s critique, though written later, reflects values directly traceable to Zhe-school doctrine and is often cited in discussions of orthodox qin aesthetics.

Clarifying Notes (Section 3.3)

1. “Wu school” as a regional designation

In Ming–Qing discourse, “Wu school” often denotes the geographical location of activity rather than an independent stylistic system. Here it functions as a regional manifestation of Zhe-school transmission.

2. Xu lineage as a hidden backbone

The argument advanced in this section reframes later canonical schools (notably Yushan) as structurally dependent on Xu-lineage transmission, even where this dependence is not explicitly acknowledged.

3. Multiple-source learning

The inclusion of informal or non-elite teachers (e.g. the woodcutter “Xu Yixian”) reflects a traditional valuation of experiential transmission alongside orthodox lineage.

4. Zhe school as a generative source

Rather than being treated as a closed historical school, the Zhe tradition is presented as a generative matrix whose aesthetic principles were reconfigured within later schools.

Clarifying Notes (Section 4)

1. Decline through lineage rupture

The article consistently treats the loss of continuous oral transmission as the decisive cause of decline, outweighing stylistic change or repertory survival.

2. Printed scores vs. living transmission

The survival of printed manuals is explicitly distinguished from authentic lineage continuation, underscoring the primacy of embodied practice.

3. Late-Ming divergence

The Wenhuitang Qinpu is treated as a collateral development rather than orthodox continuation, based on both musical content and unclear lineage claims.

4.Zhe school as historical matrix

Even in decline, the Zhe school is framed as a generative source whose principles were absorbed and transformed by later traditions rather than extinguished.

Chinese original (See translation)

一、古琴演奏風格的發展

古琴,從傳說中舜「削桐為琴、繩絲為弦」,或從詩經中「窈窕淑女、琴瑟友之」等記載來看,是中國歷史上最古老的彈撥樂器。在漫長幾千年的古琴發展歷史中,歷代琴家輩出,琴學資料完備豐富,從唐代發明減字譜後,琴曲記錄趨於方便和完整,自明代以來各種琴譜刊印了上百種。「琴」這一樂器緊緊契合著中國幾千年文化的脈流,在傳統文化中有著重要的地位。 從古琴的演奏風格上來說,只要不同的人演奏,在風格上便會有一定的差異性。最早追溯到公元前春秋戰國時期,《左傳-成公九年》中記載楚樂師鐘儀彈琴的故事。晉侯軍中視察,看到被抓的鐘儀,「使與之琴,操南音」。

從這個記載可以看出,鐘儀演奏的樂曲已有鮮明的地方風格,這種地方風格,一定與當地民歌以及地方語言有著密切的聯繫」(許健《琴史初編》)。

到了唐代,著名琴師趙耶利說:「吳聲清婉,如長江中流,綿延徐逝; 有國士之風;蜀聲躁急。若急浪奔濤,以一時之俊傑。」(宋‧朱長文《琴史》)。唐代琴壇出現的「沈家聲、祝家聲」,《琴史》記載唐代著名琴師董庭蘭「善沈祝二家聲調」,戎昱有詩稱贊董庭蘭「沈家祝家皆絕倒」。

宋代琴家成玉磵《琴論》中說:「京師過於剛勁,江西失於輕浮,惟兩 浙質而不野,文而不史。」

從鐘儀奏「南音」。到唐代的「吳聲、蜀聲、沈家聲、祝家聲」,一直到宋代的「江西、兩浙」的演奏風格,都是古琴這一樂器不斷發展的結果,正是琴派形成的醖釀階段。

二、南宋浙派古琴的形成

古琴流派的形成,除了大的社會文化環境的演變發展和推動以外,其自身必須具備以下條件:代表人物、明顯的演奏風格、師承關係的延續、譜系傳承。

正是應和了上述的四個條件,於是,南宋末年,浙派古琴猶如一顆璀璨 的的明珠,應時應運地出現在古琴歷史上。

1、代表人物

郭沔(約1190年前一1260年後),字楚望,南宋永嘉城內(今鹿城)人,以琴藝名於時。郭沔曾在臨安官僚張岩家裡當清客,張岩,字肖翁,乾道五年進士,官至光祿大夫,十分愛好琴,所以邀請了郭楚望在家裡研究古琴,切磋琴藝。這段時間,郭楚望接觸到大量的張岩的官藏「閣譜」和民間流傳的「野譜」,極大地開闊了眼界,因之琴藝珍日臻精化,最後脫穎而出,成為了一代大家,開創了浙派一脈。郭楚望的創作曲目有《瀟湘水雲》、《泛滄浪》、《秋鴻》等。

楊纘,字嗣翁,號守齋,又號紫霞錢塘人,官至司農卿。據《齊東野語》稱,他好古博雅,尤精琴律,能依調制曲,楊纘與他的門客毛敏仲、徐天民兩位琴師經常切磋琴藝。楊纘晚年時將多年研習的郭沔傳譜與從民間收集的眾多曲譜匯集,編成《紫霞洞譜》十三卷,錄曲四百八十六首,是歷史上第一部規模宏大的古琴譜集,被時人稱為 「浙譜」。

徐宇,字天民,號雪江、瓢翁。師從於郭楚望的弟子劉志方,精於琴藝,時以琴名。他與毛敏仲同為楊纘的門客,一起編寫琴譜。創作流傳下來的有《澤畔吟》一曲。徐天民開創了元明時代「浙派徐門」一脈,古琴在家族內代代相傳,幾百年間,使得南宋浙派古琴得以興盛和發展。

毛遜,字敏仲,浙江衢州人。初學「江西譜」,後改學「郭(楚望)譜」,琴技精純。創作曲有《漁歌》、《樵歌》、《佩蘭》、《山居吟》、《莊周夢蝶》等。他與徐天民同在楊纘門下做門客,一起精研琴藝,編纂琴譜。毛氏的琴曲創作,豐富了南宋浙派古琴的曲目,為南宋浙派古琴的發展作出了巨大的貢獻。

2、琴派演奏風格

南宋浙派古琴創始於南宋,發展、流傳於元,興於明。琴派本身的出現,是繼承了前人演奏的精華,在後續的幾百年中,琴家輩出,形成了獨特的演奏風格。茲從以下幾點敘述:

(1)追求器樂本身的表現能力。宋成玉澗《琴論》評論當時各地琴風是說:「京師過於剛勁,江西失於輕浮,惟兩浙質而不野,文而不史」。當時的「江派」比較注重於歌唱,一按彈間,無不以歌詞相應。而浙派強調樂器的本身表現功能,就像《杏莊太音補遺》上說:「琴制於伏羲之世,有音無文者也,後人釋以文,妄矣。謹依先言,去文以存勾剔。」。在現存的明代浙派琴譜中,《梧岡琴譜》所收29曲,只有一首《歸去來辭》是琴歌,《杏莊太音補遺》中所錄72首琴曲,無一首琴歌。

(2)指法規範潔淨。自唐代發明減字譜以來,右手指法一度繁復,《神奇秘譜》之《太古神品》中收錄的一些早期琴曲中出現的右手指法,如「卻轉」、「全牽」等,在浙派琴譜里已經少有出現,右手無名指「打」和「摘」的運用,也大量減少。這是因為浙派琴家主張強調樂器的表現,所有指法為音樂形象服務,所以在後期指法的發展中,更重視其演奏的合理性和表現,明代劉珠《絲桐篇》:「其江操聲多繁瑣,浙操多舒暢,比江操更清越也」。明代浙派琴譜《文會堂琴譜》中說浙派的演奏風格「潔淨而精當」。

《杏莊太音補遺》中收錄「彈琴啓蒙」詩一首,說是「徐夢吉作」。詩日:「聲完綽注須從遠,音歇飛吟始用之。彈欲斷弦方得妙,按令人木乃稱奇。輕重疾徐蒙接應,撞揉行走怪支離。人能默會其中意,旨趣雖深可盡知。」徐夢吉是浙派徐門的大家,作者把這首詩寫在這裡,一方面是強調琴譜傳承的正統性,另一方面,這首「彈琴啓蒙」詩的確是古琴演奏的要旨,反映 了南宋浙派古琴演奏技巧的嚴謹,讀之極具神采。乾南宋浙派古琴演奏指法的研究很有參考價值。

(3)琴曲規模大。在《梧岡琴譜》里所錄29首,10段以上的大型琴曲佔12首(「梅花引、漁歌、清都引、鶴鳴九皋、瀟湘」10段;「猗蘭、樵歌」11段; 「禹會塗山」12段;「陽春、雉朝飛、佩蘭」13段;「秋鴻」35段);6至9段的中型琴曲14首(「歸去來辭、屈原問渡」6段;「亞聖操」7段、「文王操、關雎、南風暢、昭君引、御風行」8段;「白雪、長清、猿鶴雙清、莊周夢蝶、烏夜啼、楚歌」9段);3段的小型琴曲3首(「懷古吟、鶴舞洞天、飛飛鳴吟」)。

其實「長清、莊周夢蝶、烏夜啼」等曲都是演奏級別不低的琴曲,演奏時間也有9分鐘以上,所以從這點意義上說,《梧岡琴譜》所收錄的大型琴曲佔一半以上。

(④)作曲技法豐富,手法靈活。如《杏莊太音補遺》中「佩蘭」一曲,羽調式,作者運用了「67123#456」的七聲雅樂音階,其中「偏音」變化豐富,是中國傳統律學的活化石,旋律優雅,頗具研究性。在《瀟湘水雲》、《樵歌》、《白雪》等曲中,經常用到一些變音。如《白雪》中,多處用到了偏音#4,又迅速回到5,泛音#4的使用,使雪花飛舞、晶瑩剔透的形象得到提升。浙派這些作曲技法的使用,增加了樂曲的色彩,對於表達特定的情感有推波助瀾的效果,音樂的效果更具可聽性。在後世的琴學發展中,早期明代琴諧中的這些「變音」都被後人歸納到五音里,使得琴樂漸漸失去了一些原汁原味的風貌,殊為可惜。

(5)演奏樂曲體系豐富而完備。琴曲編錄比較務實,重視音樂的表現技巧,不像有些琴譜為迎合時勢而收錄一些阿諛奉承的無實質性內容的曲子。從《梧岡琴譜》和《杏莊太音補遺》來看,琴曲分類涉及以下四類:

儒學類:「猗蘭、亞聖、文王」等

道家類:「列子御風、莊周夢蝶」等

山水應景:「鶴舞洞天、樵歌、漁歌、梅花引、陽春、白雪、長清、欸乃、瀟湘水雲等」

歷史人立:「古交行、楚歌、昭君引、屈原問渡、離騷、歸去來辭」等。

歷史人文:古交行,楚歌,昭君引,屈原問度,離騷,歸去來辭 等。

在明代三本代表性的浙派琴譜—《梧風琴譜》、《琴譜正傳》和《杏莊太音補遺》中,前兩者所錄琴曲基本雷同,《杏莊太音補遺》的編者蕭鸞講究 「曲必有吟」,在每首琴曲前加上類似風格的小曲,如「衝和吟」(應「陽春」)、「孤芳吟」(應「梅花三弄」)、「思歸吟」(應「猗蘭」)、「山居吟」(應「樵歌」)等。使得演奏曲目更加豐富。

3. 師承延續

南宋浙派古琴一脈,從郭楚望創始以來,傳承相當規範和嚴謹.

Chart

從歷史記載上整理,南宋浙派古琴比較重要的傳承關係脈絡如下:郭楚望一劉志方一毛敏仲、徐天民、楊纘一徐秋山、袁桷、金如礪一徐夢吉、宋尹文一徐和仲一徐惟謙一張助一戴義一黃獻、蕭鸞等。

在上述的這條傳承脈絡中,每個琴家都是在古琴史上極具重量級的人物。並且可以清晰的看到徐氏一脈的家族傳承關係。徐天民一徐秋山一徐夢吉一徐和仲一徐惟謙。《杏莊太音續譜》記載:「遠而林壑,微而聞闌。所致諸曲,動日徐門」。明代劉珠《絲桐篇》記:「習閩操者百無一二,習江操 者十或三四,習浙操者十或六七。」從元代至明代,期間歷經幾百年,徐氏家族在浙派琴藝的傳承發展上擔當起了歷史的大任,正是由於徐氏一族和歷代其他琴人的努力,使南宋浙派古琴一度威震琴壇,成為元明時期領導古琴風尚的中堅力量,並對後世琴學產生了巨大的影響。

4、琴譜譜系傳承

宋初以來琴譜有了宮廷御用的「閣譜」和流傳於民間的「野譜」之分,南宋時官至光祿大夫的張岩十分好琴,蒐集了大量的官藏「閣譜」和「密貝瓦市」的「野譜」,編成《琴操譜》十五卷和《調譜》四卷(未出版,供失)。在張岩家裡做清客的郭楚望,幫助張岩一起整理研究琴譜,大量接觸到琴譜資料,吸取了傳統琴曲中的各種養分,開闊了眼界,終於釀育出了南宋浙派古琴的開山祖師。

浙派琴譜的整理和傳承上,楊纘作出了不可磨滅的貢獻。楊纘(上文已有介紹)專門派徐天民師從劉志方,學習郭楚望的傳譜,晚年時匯集眾多曲譜編成《紫霞洞譜》十三卷(佚失),錄曲四百八十六首,是歷史上第一部規模宏大的古琴譜集,被時人稱為「浙譜」。取代了當時民間十分流行的「江西譜」。

這個譜集的問世和其中琴曲的廣泛流傳,為南宋浙派古琴的興起打下了 扎實的基礎。

焦竑《國史經籍志》載徐天民著《徐門琴譜》十卷(佚失)。

徐天民的弟子金如礪,琴學上很有成就,《歷代琴人傳》中說他:「盡得徐君之妙,又能玄探少師譜外不傳之意。」金如礪將徐所傳的琴曲,按五音各出一調、一意、一操,共十五曲,編成《霞外琴譜》(佚失)。成為浙派代表性的琴譜之一。

南宋浙派古琴至徐氏徐和仲一代,大興。徐和仲琴藝「得心應手,趣自 天成」。徐編有琴譜《梅雪窩刪潤琴譜》(佚失)。

黃獻,字伸賢,號梧岡,十一歲人宮,師從宮內琴師戴義。黃獻自稱:「朝夕孜孜,頃刻無息,於1546年編成《梧岡琴譜》,刊印出版。《梧岡琴譜》是明代存見的第一部明確為「浙派徐門正傳」的琴譜,對南宋浙派古琴藝術的的研究極具參考價值。

與黃獻同時代的的蕭鸞,字杏莊,陽武人。自幼學琴,精研南宋浙派古琴,「一日莫能去左右,計五十餘年。」於1557年,編成《杏莊太音補遺》。 共三卷,收72首琴曲。

同時期還有楊嘉森編於約1561年的《琴譜正傳》,所錄琴曲與《梧岡琴譜》同。

錢塘胡文煥,於1596年編《文會堂琴譜》,共六卷。前三卷為論琴文字, 後三卷收編著「親傳之浙操」的六十九曲。譜記「今余此譜。皆親傳之浙操,未經梓,有目者當識其秘也」。強調了該譜是未經刻印的浙派秘本。

從以上的史料記載和現存琴譜來看,浙派琴譜一直到明代,其琴譜傳承是一直延續著的。琴譜的傳承,是南宋浙派古琴在幾百年間得以傳播和興旺的主要原因之一

三、南宋浙派古琴對後世琴學的影

1、系統地總結了歷代的琴曲。

唐代曹柔等琴家發明減字譜後,琴曲記載變得方便,琴曲的成譜數量加大,各地傳世琴曲便良莠不齊,宋代官方「閣譜」和民間「野譜」規模巨大,從郭楚望整理張岩的《琴操譜》,形成自己演奏特色的「郭譜」,到經其弟子劉志方傳至徐天民,一起歸人楊纘整理的《紫霞洞琴譜》,後世浙派琴人整理之《徐門琴譜》、《霞外琴譜》等,這些琴譜雖已佚失,但從所載琴曲的規模和類編上,無疑是對歷代琴曲的規範化和專業化的整理,對古琴的良性發展是極有意義的。

現存《梧岡琴譜》、《杏莊太音補進》、《文會堂琴譜》等,更是保留 了歷代浙派名曲,是古琴音樂和傳統文化中的珍貴資料。

2、規範、整理歷代古琴演奏指法,加強了古琴作為樂器的獨奏表現功能。

南宋浙派古琴一脈,從現今《梧岡琴譜》、《杏莊太音補遺》等傳譜中的記譜指法看,較為規筒、務實並准當。諸如右手指法中,無名指「打」和 「摘」已經基本不用;前朝的各種右手繁復指法如 「卻轉」、「全牽」、「送輪」、「緩起轉」等基本不用,各種「大小短長鎖」、「換指鎖」、「背鎖」等,在《梧風琴譜》里只出現了「長鎖」、「短鎖」、「背鎖」、「小鎖」四種。左手指法吟揉指法種類不多,在《梧岡琴譜》里「吟」分為「退吟」、「走吟」和「」三種,「猱」以「撞」居多,左手走手音和吟猱指法在琴曲中所佔比例較同時期其他譜本多,配合「帶上」、「換指」等特色變化的交替使用,體現了浙派對左手韻法的重視,體現了古琴曲從早期的「聲多韻少」向「聲少韻多」發展的過程。

南宋浙派古琴講究「去文以存勾剔」,音樂審美取向講究純器樂曲的意境表達,直擊當時琴壇的「江派」的以文「對音」、華麗輕浮之風氣,對於古琴這一樂器本身的技巧發展起了很大的作用。

清代浙派琴家高濂曰:「今人不究意旨,不親明師,不講譜法,不媧手勢,遂使聲之曲折,手之取音,緩急失宜,起伏無節,知聲而不知音,運指而不運意,奚取彈為?有等務尚花巧急驟,誇奇逞高,不求法度。準繩之中有敷暢悠揚之妙,操多散聲,以類箜篌;巧取接聲,以同箏阮;大失雅音,重可笑耳。」

3、對其他琴派的形成起了推動和滲入作用

清人蔣文勳在《琴學粹言》論琴派時說:「世所傳習,多宗吳派,雖今蜀人,亦宗吳派矣。吳派後分為二,日虞山,日廣陵。虞山派者,明神宗時,常熟嚴天池先生當琴學寢微之際,黜俗歸雅,為中流砥柱,家住虞山, 一時知音者翕然尊之,為虞山宗派,人比之古文之韓昌黎,岐黃之 張仲景。…‧天池之琴,受之陳星源,…‧‧星源之尊人愛桐先生,為當時之冠。愛桐傳之張渭川,渭川傳之徐青山,青山傳之夏於澗。其時名流有施礙盤、沈太韶、戈莊樂、趙雲所、谷雲樵、陸九來諸人。」劉承華在《南宋浙派對後世琴派的影響之脈絡》一文中說:「蔣文勳這裡所說吳派,實際上就是浙派的余脈。當時有不少徐門弟子在蘇州一帶做官或講學,例如徐天民之孫徐夢吉在常熱,徐門高足張助在蘇州等。因此,所謂‘吳派’應該就是在吳地的浙派,是徐門的余脈。當時在吳地確實還存在著另一派—一江派,即所謂 ‘浙操徐門,江操劉門’。此派主要在松江(今上海境內) 。但江派的風格與後來的虞山派差別較大。虞山派是以清和淡逸為宗旨,而江派則‘多繁瑣’…‧ 因此,虞山派所宗之吳派不會是江派,那麼,就只能是浙派。這樣,虞山派和廣陵派的淵源於吳派,實際上就是淵源於浙派了……虞山派的創始人嚴澄(號天池)的琴學淵源來自四個方面:1、徐門的影響,徐和仲之父徐夢吉曾在常熟教書,使徐門琴學也傳入常熟;2、向著名琴家陳愛桐之子陳星源學琴,而陳愛桐又是徐夢吉的再傳弟子,故與前一條有同源關係;3、向不知名的樵夫(嚴稱他為‘徐亦仙’)學琴;

4、吸取京師著名琴家沈音(字太韶)之長,補己之短,而沈音也是浙派琴人。」 琴家查阜西先生多次提到:「虞山派實則 是浙派的後身」 「其江操聲多煩瑣;浙操多疏暢,比江操更覺清越也。」(劉珠《絲桐篇》),嚴天池對於世傳浙派一脈的風格,吸收了「清越」特色,融人其本人的學養琴藝,,對當時琴壇雜沓輕浮的琴風進行改新重樹,建立「清、微、淡、遠」的琴風,形成了虞山派的自身特色,對後世琴學影響很大。 蔣文勳說:「廣陵派者,國初楊州徐二勳先生,善琴名世。 其嗣晉臣,傳其家學,刻之《響山堂》。後年允恭又刻之《澄鑒堂琴譜》。其氣味與熟派相同」,揚州和廣陵地處相近,琴人之間交流頻繁,其演奏風格互相影響和滲透,是在情理之內。

光緒二年(1876)有唐銘彝、葉介福、張孔山等刊傳了蜀派《天聞閣琴譜》,張孔山(號半髯子)是蜀派是最重要的代表。而他本人是浙江人,曾學琴於浙派琴師馮彤雲。後在青城山當道士,其所傳琴曲如七十二滾拂《流 水》在琴壇上流傳至今。

明清琴派以常熟虞山派和廣陵派為開端,在其影響下,繼有金陵、諸城、嶺南、九嶷、浦城、梅庵等,各家相互影響交融,各放光輝,很大地推進了和發展古琴演奏技藝和風格,追溯到浙派,其所傳之琴統,蓋大且深遠矣!

四、南宋浙派古琴的衰微

從以上師承關係和琴譜傳承來看,浙派自南宋末年郭楚望創立後,經過劉志方、毛敏仲、徐天民、楊纘等諸浙派琴家的努力,已經光芒顯露,元代著名琴家袁桷、金如礪、何巨濟等都師從於徐天民學琴,成就斐然。袁桷著有著名的《琴述》,論述了宋代譜系的演變,從官方「閣譜」 的衰亡到民間「江西譜」的興起,以及宋朱「浙譜」的取而代之,對浙譜的形成提供了具體的歷史資料,在琴學研究方面具有很高的價值。金如礪是杭州開元宮道士,琴藝高超,《歷代琴人傳》中曾對他這樣評價:「盡得徐君之妙,又能玄探少師譜外不傳之意。」他編成《霞外琴譜》。成為浙派代表性的琴譜之一。

元代的浙派琴家和浙派琴譜、琴著的出現,對浙派古琴的進一步發展推 動的作用是巨大的。

至於明代「迄今上自廊廟,下逮山林,遞相教學,無不宗之,琴家者流,一或相晤,問其所習何譜,莫不曰徐門」(劉珠《絲桐篇》)。「從這些描述看起來,當時人們學習‘徐門’的狂熱程度,並不亞於今天人們對名歌星的迷戀」。許健《兩浙琴派的興起及其演變》)

明末清初,浙派琴人分流至吳、常熟等地,隨著虞山派、廣陵派的興起,浙派漸漸趨於式微,直至後來有述著中提及,而琴家無人,傳承不繼。南宋浙派在興盛一時後,退出了歷史舞台。

縱觀中國琴史和南宋浙派之演變,其在明代後式微直至消失,是有歷史 和本身的原因的,主要因為「師承關係」的斷裂。

南宋浙派從郭楚望起,一直到明代黃獻、蕭鸞等琴家,歷經十代傳人,其師承關係脈絡清楚,傳承有序,期間浙派琴藝大力發展,從現今存譜來看,《梧岡琴譜》、《杏莊太音補遺》和《琴譜正傳》三本琴譜,所刊同名琴曲大致相同,說明其傳承之嚴謹。稍晚於三本琴譜後刊行的《文會堂琴譜》,裡面的同名琴曲已經發生了一定程度的改變,如《梅花三弄》里的泛音主題中的兩句「1555」在《梧岡琴譜》等三本里是沒有連接音的,而在《文會堂琴譜》里已經加上了「32」 的連接音。如《樵歌》第五段,《梧岡琴譜》等譜中是左手名指跪五徽七六弦,在《文會堂琴譜》里被取消,代之以左手大指按弦。而且旋律也發生了變化。《文會堂琴譜》的編者胡文煥,稱「今余此譜,皆親傳之浙派…」,但琴譜里傳承關係,胡氏本人的師承關係也未明確。從譜本的情況來看, 與其他浙派傳譜還是有一定的區別。我們可以暫時認為是南宋浙派所傳下來的旁支。

而到了清乾隆九年(1744年),錢塘由蘇璟等人合編了《春草堂琴譜》,由於編者等人是錢塘(杭州)人,這本琴譜也被後人稱謂浙派傳譜,但筆者考了裡面諸如「《佩蘭》、《猗蘭》、《梅花三弄》」等數曲,和明代浙派傳譜已經大相徑庭,不是原來意義上的浙派了。

所以,從明代黃獻、蕭鸞等人以後,其實真正的南宋浙派一脈的傳承已經斷裂。雖有譜本傳世,但沒有了口傳心授的師承關係,其傳播和發展必然大受影響。

清代政治文化環境的苛刻,讓琴人們更多地去追求古琴音樂的道統功能,對左手的吟猱、走手音技巧大加發展,對於虞山派所樹的「清微談遠」之琴風則爭相推崇,而虞山派的《松弦館琴譜》,對於節奏快速的曲子如《瀟湘水雲》、《烏夜啼》等琴曲一概不錄。這在一定程度上反而忽視了器樂功能表現的多面性,這一點和南宋浙派的器樂表現主張是不一致的。

在明代黃獻、蕭鸞等琴家後,明確的浙派傳承已經沒有,但浙地琴家還是不斷地出現,如上文提到的一起編寫《文會堂琴譜》的錢塘琴家蘇璟、戴源等人。龍游籍琴家和斫琴家祝海鶴(龍丘道人)、西塘琴人高騰、龍泉琴家吳金陵、餘杭琴家嚴調御等,但和南來浙派或者浙操徐門一系都沒有傳承關係。 後人稱之為浙派琴家,其實只是地理上的稱謂而已。

至於清代的錢塘琴家如陳大斌(太希)、陸堯化、虞謙(樵谷)等,比較祟 尚琴歌,和南宋浙派之風貌更是遠不相及了。

許健先生在《兩浙琴派的興起及其演變》中說:「兩浙琴派始於宋,盛 於明,變於清,在我國琴史中舉足輕重。」

但從本文所述看,明代後期師承關係傳承的斷裂是其衰微的主要原因,所以南宋浙派始於宋,盛於元明,而式微於明末。若說清代還有「浙派」或「新浙派」之稱,那也只是地域概念上的稱謂了,和南宋浙派已無實質性的傳承關係。

浙派古琴至明末衰微後,其零藝並沒有消亡,而是完成了其幾百年的承繼琴學的大任後,將其營養和精華部分灌輸到了其他各地琴壇,致使各地各具特色的多家琴派興起,爭嗎羅壇,無疑,南宋浙派對後期琴派的影響是巨大的。