|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| WGQP ToC / Qinpu Zhengchuan Handbook List QSCB 7a Comparative chart | 網站目錄 |

|

Wugang Qinpu

Wood Ridge Qin Handbook 1 |

梧岡琴譜

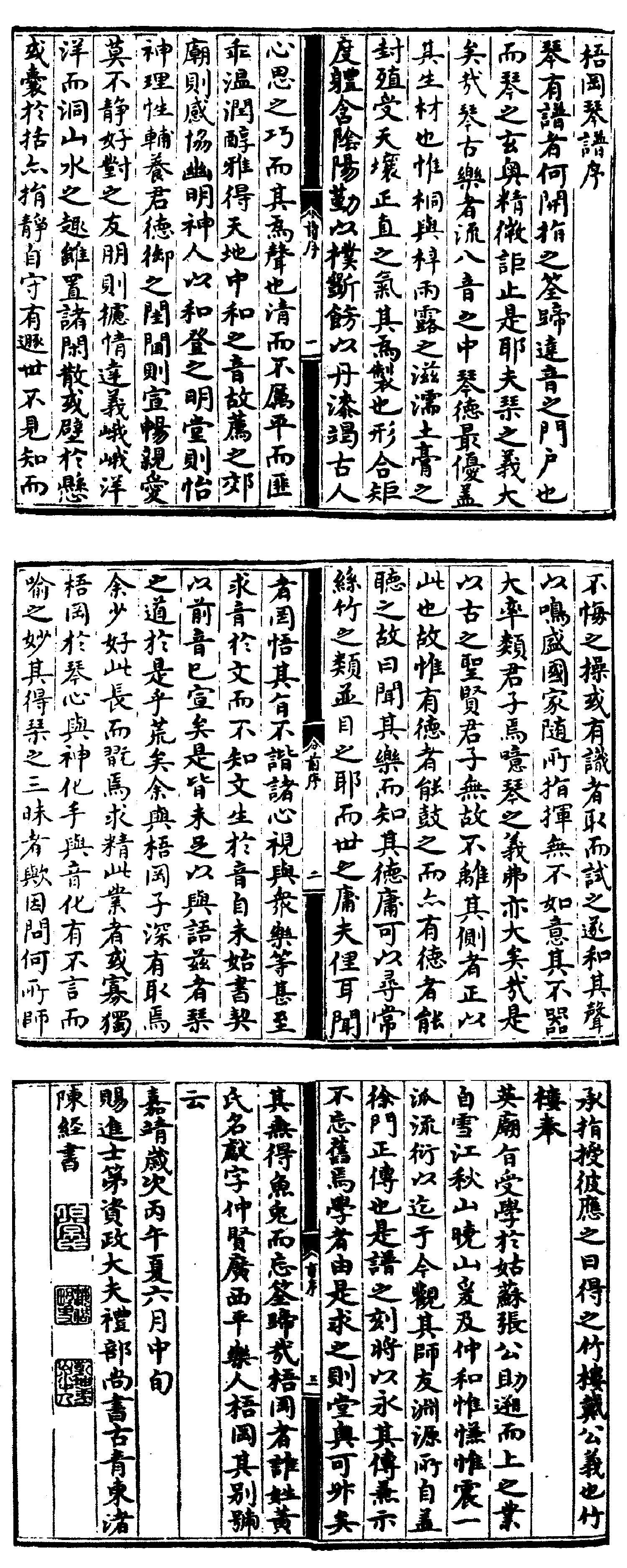

QQJC I/395-465; 1546 Preface by Chen Jing (expand)2 |

This handbook, compiled by the court eunuch Huang Xian (see his afterword),3 has 42 melodies, all of them versions of melodies found in earlier handbooks, though occasionally with changes in the names and in at least one case an entirely new melody. Nevertheless it is said to have the earliest surviving qin tablature for melodies attributed to the Xu family orthodox tradition.4

This handbook, compiled by the court eunuch Huang Xian (see his afterword),3 has 42 melodies, all of them versions of melodies found in earlier handbooks, though occasionally with changes in the names and in at least one case an entirely new melody. Nevertheless it is said to have the earliest surviving qin tablature for melodies attributed to the Xu family orthodox tradition.4

Since my policy has always been to re-construct the earliest version of any particular melody this has meant I have done little reconstruction from Wugang Qinpu. What I have done includes,

); new version; link to transcription

The preface by Chen Jing (shown at right)5 says that this qin tradition originated with the famous 13th century qin master Xu You (Xu Tianmin).6 At the end of the Song dynasty Xu was a "house guest" of the famous collector Yang Zuan.7 The preface then outlines the transmission of the music from Xu Tianmin to Zhang Zhu,8 who came to the Ming court in Beijing and taught the eunuch Dai Yi,9 a teacher of Huang Xian,10 also a court eunuch. Huang Xian compiled the handbook and provided an afterword (see at right and below) that give some detail of qin activities at the court.

If tablature in Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425) was actually copied from surviving qin tablature in the collection of Yang Zuan, the Xu family tradition might thus document either a separate Song dynasty tradition, or a separate transmission of the same music over several generations.11 Although none of the 42 titles in Wugang Qinpu was new, all the melodies have differences from earlier versions and some seem to be completely different.12 What has not been determined is whether any of these differences in fact represent an earlier tradition.13

In 2015 the Hangzhou qin player Chen Chengbo published transcriptions of nine of the 42 melodies, and these are recorded on a CD by ROI.14

Preface

by Zha Fuxi

from Qinqu Jicheng, Vol. 1

Beijing, Zhonghua Shuju Chuban Faxing, 1981

15

See also Qinpu Zhengchuan

(This handbook) in the collection of the Beijing library,16 printed in the Ming dynasty, (is) a specialized collection of qin tablature compiled by (the eunuch) Huang Xian of Pingle county in Guangxi province. In front there is a preface by Chen Jing dated 1546. The book is divided into two folios. At the end of the (2nd) folio is an afterword (also dated 1546) by Huang Xian. Altogether there are 42 pieces. (One has lyrics.17)

In my opinion (Wugang Qinpu) is what is listed among the reference books in the Yuelü Quanshu of Zhu Zaiyu18 as the Zhang Zhu Qinpu (Qin Handbook of Zhang Zhu).19 Huang Xian's afterword clearly shows it is the original tablature of Zhang Zhu; the preface by Chen Jing clearly shows that Zhang Zhu's qin (music) was an outflowing from the Southern Song school of Xu Yu, (and) that there was an orderly lineage among teachers and friends; it is called the "Xumen Zhengchuan" (Correct Tradition of the House of Xu; see this Xu tradition chart and its related footnote). Zhang Zhu, a commoner who played qin, was summoned (to the palace) by the Ming Xiaozong emperor (reign title Hong Zhi, 1488-1505) to teach the Xumen Zhengchuan to the eunuch Dai Yi. Huang Xian, also a eunuch, studied Xumen Zhengchuan from Dai Yi. The founder of the Xumen (Zhengchuan), Xu Yu, had in turn been a disciple of the Song dynasty's Guo Mian.20 This shows clearly that the Zhejiang school Xumen Zhengchuan, which inherited Guo Mian's style of taking its models from the rustic music of ordinary people, was still current among the people during the middle period of the Ming dynasty.21

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Woodridge Qin Handbook (梧岡琴譜 Wugang Qinpu)

15169.5 only 梧岡 Wugang, nickname for various people; 15169.10 has 梧岡道人 as a nickname of 黃獻 Huang Xian (see below), but it adds nothing and gives no reference, plus there doesn't seem to be an entry for the name Huang Xian. The entry in Qinshu Cunmu has three lines, quoting information about Huang Xian found in Qianqingtang Shumu, which calls it Huang Xian Wugang Qinpu.

Some transcriptions and recordings are available.

(Return)

2.

Preface by 陳經 Chen Jing to 梧岡琴譜 Wugang Qinpu (I/397)

"Woodridge Qin Handbook".

The text (see original see at top) is as follows:

因問何所師

承指授。

彼應之曰:得之竹樓戴公義也。竹

樓奉

梧岡者,實姓黃

氏,名獻,字仲賢,廣西平樂人,梧岡其別號

英廟旨,受學於姑蘇張公助,通而上之業,

自雪江、秋山、曉山、愛及、仲和、惟慊、惟震,一

派流衍以迄于今。觀其師友淵源所自,蓋

徐門正傳也。是譜之刻,將以永其傳,兼示

不忘舊焉。學者由是求之,則堂奧可升矣,

其無得魚而忘筌蹄哉!

云。

嘉靖歲次丙午,夏六月中旬。

賜進士第、資政大夫、禮部尚書、古青東渚

陳經書。

(三個圖章)

Tentative translation:

The meaning of the qin is great indeed. The qin belongs among the ancient kinds of music; within the Eight Sounds, the qin’s virtue is the most excellent. For as to the material from which it is born, it is only paulownia and catalpa: moistened and nourished by rain and dew, built up and fostered by rich soil, receiving the firm, upright, and correct vital force of Heaven and Earth. As to its lofty making, its form accords with square and rule; its ritual import contains yin and yang. One labors at it with plain cutting and carving, adorns it with vermilion lacquer, and meets—through the ingenuity of the ancients’ minds and thoughts—the fitting craft.

And as for its sound: clear yet not clinging, even yet not deviating; warm, and mellow, pure and refined—attaining the music of Heaven-and-Earth’s balanced harmony. Thus when it is offered in the suburban sacrifices, it brings the hidden and the manifest into responsive accord, and spirits and men are harmonized. When it is brought up into the Bright Hall, it gladdens the spirit and orders the inner nature, assisting the nurturing of the ruler’s virtue. When it is employed within the women’s quarters, it gives free course to affection and intimacy, and all become calm and well. When it is set before friends and companions, it pours forth feeling and conveys meaning—lofty and spacious, broad and abundant—so that one penetrates the delight of mountains and waters.

Only if one places it among leisure and withdrawal—whether hanging it upon a wall, or wrapping it and storing it in a bag—still one casts off turmoil and guards stillness, possessing the bearing of one who withdraws from the world, is not recognized, and yet does not regret it. Or, if there is some discerning person who takes it up and tries it, then its sound is brought into harmony and made to ring forth in praise of a flourishing realm; whatever the fingers direct, nothing fails to answer one’s intent. Its not being a mere “implement” is, in general, akin to the noble man.

Ah! Is not the meaning of the qin great indeed? Therefore among the sages and worthy men of old, none, without cause, failed to keep it at his side—precisely for this reason. Thus only one who has virtue can strike it, and likewise only one who has virtue can truly listen to it. Hence it is said: “Hear its music, and you know its virtue.” How could one place it on the same level as the ordinary kinds of silk-and-bamboo music?

Yet the vulgar men of the age, with rustic ears, hearing it, are blind to its intent and find nothing in their hearts that resonates with it; they look upon it as no different from the other musics. Some even seek sound within the written words, not knowing that writing is born from sound: before there ever were written tallies and contracts, sound was already proclaimed. Such men are not those with whom one can speak of these matters. The Way of the qin is thereby brought to desolation.

I and Master Wugang (Huang Xian) have deeply taken something from it. I loved this when young; when grown, I practiced it, seeking refinement in what became my life’s craft, keeping it clear and, at times, solitary. As for Wugang 's connection to his qin: his mind transforms with the spirit; his hands transform with sound. There is in him a marvel by which, without speaking, one is made to understand — has he not obtained the “threefold savor” of the qin?

I therefore asked (Wugang) from whom he had received his lineage and personal instruction. He replied: “I obtained it from Master Dai of Zhulou". Zhulou, by imperial command in the Yingzong reign, had received instruction with the help of Master Zhang Zhu of Gusu (Suzhou). Having absorbed that, he carried it forward. From Xuejiang, Qiushan, Xiaoshan, Aiji, Zhonghe, Weiqian, and on through Weizhen, it has flowed in a single stream down to the present. When one looks to the roots and sources of his teachers and friends, it is truly the orthodox transmission of the Xu lineage.

The carving of this handbook is intended to make its transmission endure, and also to show that the old ties are not forgotten. Students, by seeking it from here, may ascend into the inner chambers; let them not, having gotten the fish, forget the trap and the snare!

As for Wugang: his true surname is Huang; his given name is Xian; his courtesy name Zhongxian; he is a man of Pingle in Guangxi; Wugang is his alternative sobriquet.

In the bingwu cyclical year of the Jiajing reign (1546), in mid-June of summer, written by the Presented Scholar by imperial favor, Grand Master for Assisting Toward Good Governance, Imperial Secretary in the Minister of Rites, Chen Jing, from an Eastern Islet of Ancient Verdancy).

(Return)

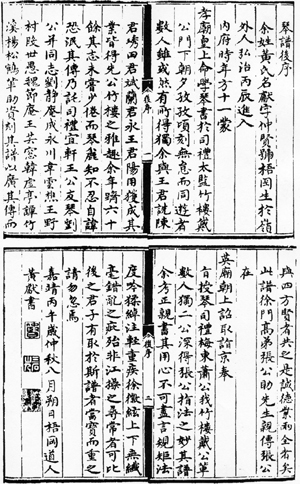

| 3. Afterword by Huang Xian (嘉靖丙午 1546; see original at right; I/465) | Afterword by Huang Xian (expand) |

The original text at right goes as follows, with translation immediately after:

The original text at right goes as follows, with translation immediately after:

琴譜後序

余姓黃氏,名獻,字仲賢,號梧岡。生於嶺外人。

弘治丙辰,進入內府,時年方十一。

蒙孝廟皇上命,學琴、書於司禮太監竹樓戴公門下。

朝夕孜孜,頃刻無怠。

而同遊者數人,雖或然有所得,獨余與王君詵、

陳君琇、田君斌、蘭君永、王君陽,

用獲成其業,皆得先公竹樓之雅趣。

余年躋六十餘,其志未嘗少倦;

而琴簏知,不忍自諱,恐泯其傳,

乃托司禮宜軒王公、友琴劉公,

並同志劉靜庵、成永川、韋雲樵、王野村、

段世愚、魏節庵、王芸窗、韓虛亭、譚竹溪、

楊松鶴輩,助資刻其譜,

以廣其傳,而與四方賢者共之,

是誠德業兩全者矣。

此譜徐門高弟張公助先生親傳。

張公在英廟朝,上詔取詣京,

奉旨授琴司禮梅東蕭公,我竹樓戴公軰數人。

獨二公深得張公指法之妙。

其譜余考正親書,其用心不可盡言。

規矩法度、吟、揉、綽、注、輕、重、疾、徐、

徽、絃、上下,無纖毫錯亂之疵,

殆非江操之尋常者可比。

後之君子有取於斯譜者,當寶而重之,

請勿忍焉。

嘉靖丙午歲仲秋八月朔日,

梧岡道人黃獻書。

My surname is Huang, given name Xian, courtesy name Zhongxian, and sobriquet Wugang. I was born beyond the southern ranges. In the bingchen year of the Hongzhi reign, I entered the Inner Court; at the time I was only eleven years old. By command of His Majesty the Emperor Xiaozong, I was instructed in qin and calligraphy under Master Dai of Zhulou, a eunuch of the Directorate of Ceremonial. Morning and evening I applied myself diligently, without a moment’s slackening.

Among those who studied together there were several persons; although some happened to gain something from it, only I, together with Masters Wang Shen, Chen Xiu, Tian Bin, Lan Yong, and Wang Yang, succeeded in completing our training, all of us attaining the refined taste of our late master Master Dai of Zhulou.

Now I have passed sixty years of age, but my resolve has never once grown slack. And as for the accumulated knowledge of the qin stored within me, I could not bear to keep it concealed, fearing that its transmission might be lost. Therefore I entrusted Master Wang of Yixuan of the Directorate of Ceremonial, together with Master Liu, a companion in qin, and also my like-minded colleagues Liu Jing’an, Cheng Yongchuan, Wei Yunqiao, Wang Yecun, Duan Shiyu, Wei Jie’an, Wang Yunchuang, Han Xuting, Tan Zhuxi, Yang Songhe, and others, to contribute funds to carve and print this handbook, so as to broaden its transmission and share it with worthy persons from all quarters. This may truly be said to unite virtue and accomplishment.

This handbook represents the direct transmission of Master Zhang Zhu, the foremost disciple of the Xu lineage. During the reign of Emperor Yingzong, an imperial edict summoned Master Zhang to the capital, where, by command, he imparted the qin to Master Xiao of Meidong of the Directorate of Ceremonial, and to several others, including our Master Dai of Zhulou. Of these, only the two masters grasped in depth the subtlety of Master Zhang’s fingering methods.

The present handbook I have examined, corrected, and written out myself; the care I devoted to it cannot be fully expressed in words. In matters of rule and measure — 吟, 揉, 綽, 注; lightness and weight; speed and slowness; hui positions and strings; upper and lower registers — there is not the slightest confusion or disorder. It is surely not something that the ordinary players of the Jiang style could ever be compared with. Those later gentlemen who find something of value in this handbook should treasure and esteem it; I ask that they do not treat it lightly.

Written on the first day of the eighth month, mid-autumn, in the bingwu year of the Jiajing reign (1546),

by Huang Xian, the Daoist of Wugang.

Some terms:

- 嶺外 Lingwai ("beyond the mountains"): refers to the far south, especially Guangxi (where Huang Xian was born) and Guizhou.

- 孝廟皇上 Xiao Miao (temple name of Xiaozong, the Hongzhi emperor)

- 英廟朝上 Ying Miao (temple name of Yingzong, the Zhengtong (1435-1449) and Tianshun (1457-1464) emperors)

- 司禮太監 Sili taijian 司禮監 was the highest eunuch office

Otherwise not yet translated.

(Return)

4.

徐門正傳 Xumen Zhengchuan (Xu Household Correct Tradition)

For further details see Xu Jian's Qinshi Chubian,

Chapter 7.A.1.

(Return)

5.

陳經 Chen Jing

Chen Jing (42618.273/2), zi Bochang, attained jinshi during 1506-22. His place of origin is not clear: at the end of his preface above he signs himself 古青東渚陳經 Chen Jing, from an Eastern Islet of Ancient Verdancy, but this is a poetic name, not a specific place name. From the preface it is clear that he was a fellow qin player but it seems as though, unlike Huang Xian, he was not specifically a student of Dai Yi.

There is also mention of the above preface in a footnote on the Xumen Orthodox Tradition.

(Return)

6.

Xu Tianmin

Xu Tianmin, proper name 徐宇 Xu Yu, also called 徐雪江 Xu Xuejiang and other names, is also discussed under

Xumen Orthodox Tradiion.

(Return)

7.

Yang Zuan

楊纘; also written 楊瓚 Yang Zan.

(Return)

8.

Zhang Zhu 張助 (more in

QSCB)

The preface by Chen Jing (I/398, line 3ff) says Zhang Zhu was from 姑蘇 Gu Su (Suzhou) and had learned 徐門正傳

Xumen Orthodox Tradition, for which he gives this lineage of seven players. These are the first seven on the following list, plus Zhang Zhu, who compiled the handbook. Huang Xian himself studied from Dai Yi, a student of Zhang Zhu. So a more complete list is as follows:

- 徐天民

- (Xu) Xuejiang (Xu Tianmin),

- 徐秋山(Xu) Qiushan,

- 徐曉山(Xu) Xiaoshan (徐夢吉 Xu Mengji)

- 徐愛及 Aiji (? No further information at present)

- 徐詵 Xu Shen (referred to here as "和仲和 Xu Zhonghe" rather than "和和仲 Xu Hezhong")

- 徐惟慊 Xu Weiqian

- 徐惟震 Xu Weichen

- 張助 Zhang Zhu

- 戴義 Dai Yi (see next)

- 黃獻 Huang Xian

It is not clear why the Xumen chart actually puts 徐惟謙 Xu Weiqian between Xu Shen and Zhang Zhu - the source of that information is not clear. The afterword adds nothing further on him, and I do not know whether any details are given in the reference mentioned by Zha Fuxi (see also the footnote below on the Zhang Zhu Qin Handbook).

(Return)

9.

戴義 Dai Yi

Also referred to as 竹樓戴公 Master Dai of Zhulou (the Bamboo Tower 26424.333: tower made of bamboo; studio of 宋王禹偁; nicknames for several people), but NFI at present other than that he was a eunuch and a student of 張助 Zhang Zhu.

(Return)

10.

黃獻 Huang Xian (1485-1561)

In 1496 Huang Xian (48904.1324 字仲賢,號梧岡,廣西平樂人) style name Zhongxian, nickname Wugang, was from Pingle in Guangxi. He entered the palace in 1496 as a eunuch, and on imperial command studied literature and the qin from 戴義 Dai Yi (see above). Wugang Qinpu apparently includes melodies in the Xu tradition either as he himself played them, or as they were written in tablature in his possession (or both?). His melodies are also in Qinpu Zhengchuan.

(Return)

11.

Comparing transmission in Wugang Qinpu with that of Shen Qi Mi Pu

The Zhang Zhu footnote gives an outline that tries to document the transmission of the Xu Household Correct Tradition over what amounts to about 150 - 200 years. However, there is no information as to whether or which pieces had their tablature simply recopied or which were revised based on how succeeding generations interpreted the melodies. It may thus not be possible to know to what extent the Xu family tradition changed during this period.

As for Shen Qi Mi Pu, although Zhu Quan consciously tried to find and copy old tablature, he mentions that some of it was edited. Thus, although some if not all the tablature in Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425) probably dates from the Song dynasty, without tablature from that time or from the intervening period it is either difficult or impossible to determine how exactly the alternate versions in handbooks such as Wugang Qinpu reflect an alternate Song dynasty style.

(Return)

12.

Unique nature of Wugang Qinpu

There is more about this handbook in Xu Jian,

Chapter 7a, as well as in Zha Fuxi's preface. As for melodies unique to Wugang Qinpu, its Gui Qu Lai Ci, for example, has the standard lyrics but a completely different melody. See also the

comparative chart.

(Return)

13.

Wugang Qinpu melodies: developing or preserving?

Sometimes it is possible to say that one melody clearly developed from another, but a lot more research needs to be done before one can be confident of most such determinations.

(Return)

14.

Transciptions and recordings by 陳成渤 Chen Chengbo of Hangzhou

__

The book 南宋浙派,古琴傳習錄 Nansong Zhepai, Guqin Chuanzilu (2015) has transcriptions by Chen Chengbo into number notation of nine of the melodies in Wugang Qinpu. ROI (龍吟) has published recordings of these nine on a separate CD called 浙派傳習錄 Zhepai Chuanxi Lu (composite or nylon-metal strings except as indicated). The title, translated as Attribution of Inheriting and Learning from the Zhe School, Volume I: A Woodcutter's Song (Qiao Ge) suggests further recordings are planned.

The nine melodies are:

- Qiao Ge

- Mei Hua Yin

- Pei Lan (silk strings)

- Bai Xue

- Wu Ye Ti

- Yi Lan

- Yasheng Cao

- Wen Wang Cao

- Zhao Jun Yuan

The CD booklet has English translations of Chen's prefaces to each melody plus three essays that were not translated. __

(Return)

15.

Commentary source

查阜西 Zha Fuxi; edited by 吳釗 Wu Zhao

北京中華書局出版發行

(Return)

16.

北京圖書館; still there?

(Return)

17.

One melody with lyrics: Gui Qu Lai Ci (Come Away Home;

I/421)

Two other handbooks have the same version as here:

Qinpu Zhengchuan

(II/427) and

Taiyin Buyi

(III/338). All three of these handbooks are associated with the Xumen tradition.

Other early versions are all related to the earliest, from Taigu Yiyin (1511; I/301).

(Return)

18.

朱載宇 Zhu Zaiyu

Zhu Zaiyu (1536-ca.1610) was the Ming prince who discovered equal temperament.

(Return)

19.

張助琴譜 Zhang Zhu Qin Pu

Qinshu Cunmu #176 lists only the title, with a reference to Qianqingtang Shumu; the latter gives only the title. Both books list Wugang Qinpu separately (see above).

(Return)

20.

郭沔 Guo Mian

Guo Mian, style name Guo Chuwang, was born mid-12th century in Li Shui,

Zhejiang province (about 200 km south of Hangzhou, then the capital). The

preface to He Wu Dongtian (#25) mentions the Zixiadong Pu, a

lost 12th qin handbook said to have had the transcriptions by Mao Minzhong and

Xu Tianmin of performances by Guo Chuwang.

(Return)

21.

Rustic music of ordinary people

This was clearly a political comment: the actual relationship between qin music and other genres is largely unstudied.

(Return)

Return to the annotated handbook list or to the Guqin ToC.