|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Qin bios | 首頁 |

|

Chen Yang

- Qin Shi Xu #5 |

陳暘 1

琴史續 #5 2 Small, medium and large qin: Chen Yang?3 |

Chen Yang, style name Jinzhi, was from Fuzhou (in Fujian province). In 1094 he became a zhike - graduate of a high level specialist examination.4

Chen Yang, style name Jinzhi, was from Fuzhou (in Fujian province). In 1094 he became a zhike - graduate of a high level specialist examination.4

Chen Yang's writings include:

Yue Shu (further details, with links to the original text and translations, are given below) is an encyclopedic Treatise on Music often quoted in Ming sources. It is sometimes referred to as Chenshi Yue Shu (Music Treatise of Mr. Chen)

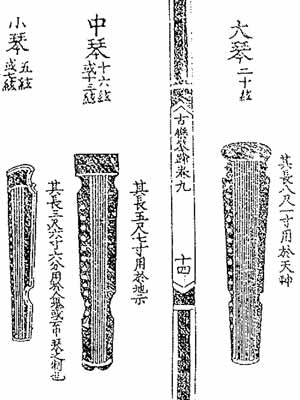

The qins in the image at right are like some of the qins depicted in Chen Yang's Yue Shu, but the image itself may not in fact be from there. Its text is also somewhat inconsistent:

The dimensions given for the small qin, also considered as medium qin, are the idealized ones for a standard qin.

The biography of Chen Yang in Qinshi Xu begins:7

The rest has no more personal information, only an extended quote from 樂書卷一百四十三 Yue Shu Folio 143.

1.

Chen Yang 陳暘 (sometimes written 陳腸; 11th-12th c.)

2.

lines. Sources cited: 宋史 Song History, 陳氏樂書 Chenshi Yueshu.

3.

Image: small, medium and large qin

4.

Zhike 制科

6.

樂書 Yue Shu; 陳氏樂書 Chen Shi Yue Shu

For hard copies, Qinshu Bielu Entry 65 lists numerous editions. The full text is most easily found in the Wenyuan Ge edition of Siku Quanshu, Vol. 211, pp. 23-949. This edition includes a contents list with each folio, but no general table of contents. The tiyao commentary at the front is repeated separately in the Siku Quanshu Zongmu Tiyao, 經 1-777 (dropping a few words from the beginning and end).

Listed in Qinshu Cunmu

(#104); included in

Shuo Fu.

Not included in Qinshu Cunmu; often quoted in the early qin writings, though much of the text in Qinshu Cunmu comes from earlier sources.

"Big qin, 20 strings. Its length is 8 chi, 1 cun. It is used for 天神 tianshen."

"Medium qin, 13 or 16 strings. Its length is 5 chi, 7 cun. It is used for 地示 dishi."

"Small qin, 5 or 7 strings. Its length is 3 chi, 6 cun, 6 fen. It is used in 人鬼 rengui. It is also said to be the construction of the medium qin."

Chen Yang, style name Jinzhi, was from Fuzhou (in Fujian). He had several official positions, up to the rank of 禮部侍郎 assistant minister in the Ministry of Rites. He specialized in 曉樂律 standards for morning music, and was especially excellent at qin....

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

Bio/1332; 42618.949 陳暘: style name 晉之 Jinzhi, from 福州 Fuzhou (in Fujian); in 1094 he 制科....

(Return)

(Return)

This image (the text is translated above) was copied from 古樂筌蹄 Gu Yue Quan Ti, part of the 李氏樂書六種

Li Shi Yue Shu (Book of Music by Mr. Li), as printed in 續修四庫全書 Xuxiu Siku Quanshu, Vol. 114, p.237 (compare 李氏樂書十九卷). The image is printed between the essays Chenshi Yue Shu (which mentions qin and se size) and Qin Se Shang Lun (see Qin Se Lun). Although this image does not appear in the Yue Shu published in the Wenyuan Ge edition of Siku Quanshu (Vol. 211, pp. 23-949), Chen Yang does include images in Yue Shu of a great variety of qin, including some with 1, 5, 12, 13 and 27 strings, a "striking qin" (image), and others that even have bridges. There is further comment on the possible significance of these images under origins.

(Return)

Chen Yang is also said to have been a jinshi. It is not clear if this is separate from his zhike. In the Song dynasty zhike seems to have referred to graduates of a specialist examination. Later it apparently referred to a special higher examination overseen by the emperor.

(Return)

An online facsimile copy of this monumental work is available

here

[e.g., Folios 137-141]. CTP also has a digital copy of the

entire work, but it is an unpunctuated OCR copy.

(See, e.g., Folio 119.)

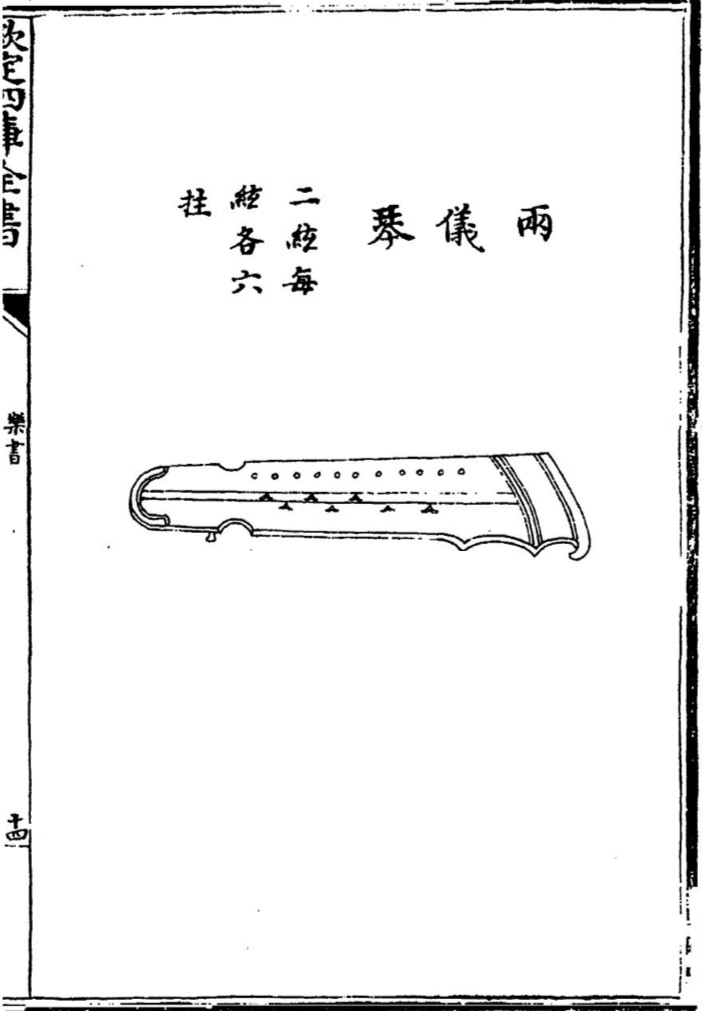

| "Qin"-related content in Yue Shu | Odd qins: a 2-string 兩儀琴 liang yi qin |

The emphasis in Yue Shu being ritual music, it is not clear whether some of the instruments from Yue Shu listed below were specifically invented for some ritual performance, then disappeared as the ritual changed; or whether there is some other reason for their impermanence. The possible significance of the great variety of these instruments is discussed further under origins.

The emphasis in Yue Shu being ritual music, it is not clear whether some of the instruments from Yue Shu listed below were specifically invented for some ritual performance, then disappeared as the ritual changed; or whether there is some other reason for their impermanence. The possible significance of the great variety of these instruments is discussed further under origins.

- Folio 119 (online; pp. 505-510 ); four 琴瑟論 essays are copied and translated in Appendix I below

- . The first three essays are called first, middle and last "Qin and Se". These and the essay after the first three of the section's seven illustrations are what is translated in Appendix I.

- 大琴 daqin: big qin (20 strings; q.v.);

- 中琴 zhongqin: medium qin (10 strings)

- 小琴 xiaoqin: small qin (5 strings); essay

- 次大琴 cidaqin: next largest qin (15 strings)

- 雅琴 yaqin: elegant qin (reference to 趙定 Zhao Ding)

- 十二絃琴 shierxianqin: 12 string qin

- 兩儀琴 liangyiqin (double ritual qin): 2 strings each with 6 bridges (sic; see image at right)

-this image looks nonsensical; text adds: "2 strings with 6 bridges each makes 12 tones"

- Folio 120 (p. 513; online)

From here three of the last four essays are copied and translated in Appendix II

A short untitled statement right after the last image

頌瑟 In Praise of Se (not online yet)

琴操 Qin Cao (begins, "自三代之治,既徃而樂經亡矣....")

步 Bu: "Pacing" (about playing open notes) - Folio 136 (p. 618; online): illustration of a jade qin (玉琴 yuqin)

The accompanying essay cites a story from 吳均續齊諧記 Xu Qi Xie Ji by Wu Jun (469 - 520) about 王彥伯 Wang Yanbo (i.e., 王沈 Wang Shen) playing such a qin. According to the story Yanbo, who excelled at qin play, once after tying up his boat at Wuyou Ting (Pavilion) heard a woman singing Chu Guang Ming, a piece played by only a few people after Xi Kang; Yanbo wanted to learn the song, so she played it again. The next morning she gave him gifts that included beautiful silks and in return he gave her a jade qin. The account concludes that because of this story people had decided that there was a jade qin.

(Further regarding the "jade qin, this story suggests that the illustration is not of an instrument actually seen, just one known by reputation. Of note also: there are a number of references in poetry to a "yuqin" (search this site for "玉琴"); I suspect they do not necessarily refer to a qin made of jade, which would have no sound and so would be purely ornamental, but to a qin with jade ornaments on it, such as the pegs and/or the studs. It could also just mean a beautiful instrument and/or one that produced sounds reminiscent of tinkling jade.) - Folio 141 (pp. 647-650;

online): illustrations of 6 types of qin, plus commentary

- 頌琴: songqin: odes qin

- 擊琴: jiqin: striking qin (further)

- 一絃琴: yixianqin: 1 string qin

- 十三絃琴: shisanxianqin: 13 string qin

- 二十七絃琴: ershiqixianqin: 27 string qin

- 素琴: suqin: unadorned qin

- Folio 142 (pp. 652-657; online): 樂圖論 Discussion of musical particulars

Discussion of miscellaneous aspects of qin. Ends with,

琴調 Qin Diao:古者琴有七例:一曰明道徳,二曰感神示,三曰議風誡,四曰恕察防,五曰制聲調,六曰流文雅,七曰善傳寫。 故宮調五妄蔡氏所撰,其心恢宏合律剛柔相應可類禮記固易商調四妾四人所制研究其理褒貶稱善可類春狄稽氏四吳曾附正請可類尚書 廣陵散寫憤歎諷刺可潁毛詩胡笳韻出殊常與正眷偕行可類文遙雜吳等曲各述其徊可類小經子吏正女所撰四德俱備可類女孝經女識復世專以聲論才藝其優房亦可知吳宋衡陽王羲羣鎮京口戴顒為之鼓琴並新聲變曲其遊絃 廣陵止息三調皆與世異大祖以其好音長給正眷伎一部顯合何嘗白鵠二聲以其羽調號為清暗其深於琴調者歟梁柳憚常以令贅轉槁古法而著清調隋鄭諱更修七始境義而為樂府曰調君子不取也 (Note mention of Guangling, Guangling San and Guangling Zhixi there and in the next section:) - Folio 143 (p.658-660?; online): 樂圖論

Discussion of musical particulars (continued); includes:

琴聲上 Qin Sounds

琴聲下

琴曲上 Qin Melodies; begins, "衆樂,琴之臣妾也;廣陵,曲之師長也。古琴曲有歌詩五篇,操二篇,引九篇。...."

琴曲下, - Folio 144 (p.661; online): 樂圖論 Discussion of musical particulars

Includes illustration and discussion of a 太一樂 taiyiyue or dayi yue, which seems to be a 12-string qin with mysterious bridges.

An online English summary (accessed 9/2010) of a dissertation on this book by 鄭長玲 Zheng Changling says the following (slightly edited):

A native of Minqing County in Fujian Province, Chen Yang was a jinshi (palace graduate) in China"s Northern Song Dynasty who later served in the Ministry of Rites. His Yue Shu, a scholarly work with a huge mass of valuable information on Song and pre-Song dynasty music, is of great historical and cultural significance. Generally regarded as the earliest encyclopedic volumes of musicology in Chinese history, and perhaps even in world history, Yue Shu has been an important and indispensable work of reference in the study of Chinese music. The 200-volume masterpiece, noted for its early date of publication and wide coverage ranging over a period between the Han-Tang dynasties and (which later influenced) the Ming-Qing dynasties, is a rare collection in the treasure of Chinese musicology. This master of Chinese musicology and the academic value, historical status and cultural significance of his Yue Shu, thus merit ampler attention. A survey of existing scholarship shows that since the 20th century most of the studies of Chen Yang and his Yue Shu have been conducted from historical perspectives. The present study attempts to approach the subject from the perspective of ethnomusicology and, against the socio-cultural background of the Northern Song Dynasty, explore Chen Yang and his Yue Shu in the context of cultural and historical development. Based on genealogical information and historical accounts obtained from field work, and drawing on relevant scholarship such as A History of the Song Dynasty, this study presents fresh information about Chen Yang"s life, including dates of birth and death, date of conferment of his academic title, place of his appointment to the office, and a Chronicle of Chen Yang. After a background study of his scholarly work in the political, economic, cultural and educational contexts of the Northern Song Dynasty, this thesis comes up with the view that the creation of the Yue Shu was motivated by the intention to restore the practice of 禮樂治國 Liyue zhiguo (Ritual Music Regulating the Country), and that to some extent the Yue Shu was influenced by the historiography and epigraphy of the Northern Song Dynasty.

(Return)

7.

Original text of the Qin Shi Xu entry

Sources given: 宋史、陳氏樂書

(Return)

Appendix I

The original text, also in Folio 119 of Chen Yang's Yue Shu, is copied here from Qinshu Daquan, where

Folio 2 entry 7 has the third section of Chen Yang's Qin Se Lun and a fourth section that only concerns qin, while entry 8 has the first section of the Qin Se Lun. The omitted section says little about the qin but it is included here as well as the fourth, but in the original order from Yue Shu, Folio 119. As mentioned above, Folio 119 also includes illustrations of various types of qin as well as further commentary.

(Qin and Se, First Part)

以理考之,樂聲不過乎五。則五絃、十五絃,小瑟也;二十五絃,中瑟也;五十絃,大瑟也。

彼謂二十三絃、二十七絃者,然三於五聲為不足,七於五聲為有餘,豈亦惑於「二變二少」之說,而遂誤邪?

漢武之祠太一、后土,作二十五絃瑟。今太樂所用,亦二十五絃,蓋得四代中瑟之制也。

莊周曰:「夫或改調一絃於五音無當也,鼓之二十五絃,皆動其信矣乎!」

聶崇義《禮圖》,亦師用郭璞二十三絃之說。其常用者十九絃,誤矣。蓋其制:

前其柱則清,後其柱則濁。

有八尺一寸、廣一尺八寸者。

有七尺二寸、廣一尺八寸者。

有五尺五寸者。

豈三等之制不同歟?

《詩》曰:「椅、桐、梓、漆,爰及琴瑟。」

《易》通:「冬日至,鼓黃鍾之瑟,用槐,八尺一寸;夏日至,用桑,五尺七寸。」

是不知美檟、槐、桑之木,其中實而不虛,不若桐之能金石之聲也。

昔仲尼不見孺悲鼓瑟而拒之,趙王使人於楚鼓瑟而遣之。其拒也,所以愧之、不屑之教也;其遣也,所以諭之、不言之戒也。

聖朝太常瑟用二十五絃,具二均之聲,以清、中相應。雙彈之第一絃,黃鍾中聲;第十三絃,黃鍾清應。

其按習也,令左右手互應,清正聲相和。亦依鍾律擊數合奏,其制可謂近古矣。誠本五音互應,而去四清,先王之制也。

臣嘗考之:《虞書》:「琴瑟以詠」,則琴瑟之聲,所以應歌者也。

歌者在堂,則琴瑟亦宜施之堂上矣。竊觀聖朝郊廟之樂,琴瑟在堂,誠合古制。

紹聖初,太樂丞葉防乞宮架之內,復設琴瑟,豈先王之制哉?

(Qin and Se, Middle Part)

If we examine basic principles, musical sounds do not go beyond five tones. Thus we have the five-string and 15-string small se ,the 25-string medium se and the 50-string large se. As for the so-called 23- or 27-string se, three is insufficient for the five-tone system, while seven exceeds it, could this idea come from (now obscure) theories of "subtracting two" or "adding two", leading to an error?

During Han Emperor Wu’s ritual sacrifices to Taiyi and Houtu, a twenty-five-stringed se was created. Today, the Imperial Music Bureau (Taiyue) also uses twenty-five strings, which aligns with the medium se of the Four Dynasties.

(According to later interpretations) Zhuangzi said: "If one alters the tuning of a single string so that it does not conform to the five tones, then when one plays the twenty-five-stringed se, all the strings will be affected."

Nie Chongyi’s Ritual Illustrations (chinaknowledge.de.) follows the claim by Guo Pu of a twenty-three-stringed se, but the most commonly used version has nineteen strings, which is incorrect.

As for its structure, (play?) in front of its zhu (柱: bridges on a se?) and the sound it clear; play behind the bridges and the sound is muddy. There exist some that are eight chi (尺) one cun (寸) long and one chi eight cun wide; some that are seven chi two cun long and one chi eight cun wide; and some that are five chi five cun long. Could these be three different standards of construction?

The Book of Songs says:

"Yitong, paulownia, catalpa, and lacquer — thus are qin and se made."

The Book of Changes says:

"At the winter solstice, the huangzhong (Yellow Bell) se is played, made from locust wood, measuring eight chi one cun."

"At the summer solstice, a se made from mulberry wood, measuring five chi seven cun, is used."

This suggests that the best materials for making qin and se are catalpa, locust, and mulberry, because their cores are solid rather than hollow. This is superior to paulownia, which, while capable of producing a resonant sound akin to metal and stone, does not match the former in substance.

In ancient times (according to Lüshi Chunqiu), Confucius refused to see 儒悲 Ru Bei because he played the se (improperly), rejecting him outright.

The King of Zhao sent a musician to Chu to play the se, only to dismiss him.

His rejection was meant to shame him and express disdain — a lesson in moral refinement.

His dismissal was meant to advise him silently, without words.

In the present sacred dynasty, the se of the Grand Sacrifices (Taichang) still uses twenty-five strings, fully encompassing both the two tonal systems (qingyin 清音 and zhongyin 中音, clear and middle tones).

The first string, when played in paired plucking, corresponds to the huangzhong (Yellow Bell) middle tone.

The thirteenth string corresponds to the huangzhong clear tone.

When practicing, the left and right hands should coordinate, producing a pure and harmonious sound.

It follows the pitch standards of bells and chimes, with the number of beats in ensemble performance conforming accordingly.

Its design can truly be said to be close to antiquity, faithfully maintaining the system of the five tones, harmonized in response, while eliminating the four extra clear tones — just as was ordained by the sages of old.

According to my own examination, the "Book of Yu" (part of the Shang Shu states: "The qin and se accompany the chant". Thus, the sound of the qin and se is meant to harmonize with the singing. Since singing takes place in the hall, the qin and se should also be placed in the hall.

Observing the sacrificial music of the present dynasty, the qin and se are positioned in the hall, which truly aligns with ancient tradition.

At the beginning of the Shaosheng era (紹聖, 1094–1098), the Assistant Music Master Ye Fang petitioned to restore the placement of the qin and se inside the ceremonial framework of the palace. But was this truly the system of the ancient kings?

Qin and Se, Final Part (Yue Shu says:)

As for the Book of Songs (Shijing), it says:

"yitong, paulownia, catalpa, and lacquer — thus are qin and se made."

The Book of Changes says:

"At the winter solstice, the huangzhong (Yellow Bell) se is played, made from locust wood, measuring eight chi one cun."

"At the summer solstice, a se made from mulberry wood, measuring five chi seven cun, is used."

This suggests that the best materials for making qin and se are catalpa, locust, and mulberry, because their cores are solid rather than hollow. This is superior to paulownia, which, while capable of producing a resonant sound akin to metal and stone, does not match the former in substance.

In ancient times:

Confucius refused to see Ru Bei when he played the se, rejecting him outright.

The King of Zhao sent a musician to Chu to play the se, only to dismiss him.

His rejection was meant to shame him and express disdain—a lesson in moral refinement.

His dismissal was meant to advise him silently, without words.

In the present sacred dynasty, the se of the Grand Sacrifices (Taichang) still uses twenty-five strings, fully encompassing both the two tonal systems (qingyin 清音 and zhongyin 中音, clear and middle tones).

The first string, when played in paired plucking, corresponds to the huangzhong (Yellow Bell) middle tone.

The thirteenth string corresponds to the huangzhong clear tone.

When practicing, the left and right hands should correspond, producing a pure and harmonious sound.

It follows the pitch standards of bells and chimes, with the number of beats in ensemble performance conforming accordingly.

Its design can truly be said to be close to antiquity, faithfully maintaining the system of the five tones, harmonized in response, while eliminating the four extra clear tones—just as was ordained by the sages of old.

I have examined this matter. The "Book of Yu" (虞書) states: "The qin and se accompany the chant" (琴瑟以詠). Thus, the sound of the qin and se is meant to harmonize with the singing. Since singing takes place in the hall, the qin and se should also be placed in the hall.

Observing the sacrificial music (郊廟之樂) of the present dynasty, the qin and se are positioned in the hall, which truly aligns with ancient tradition.

At the beginning of the Shaosheng era (紹聖, 1094–1098, during the Song Dynasty), the Assistant Music Master (太樂丞) Ye Fang (葉防) petitioned to restore the placement of the qin and se inside the ceremonial framework of the palace (宮架之內). But was this truly the system of the ancient kings (先王之制)?

(Yue Shu Folio 119 Part 4)

To follow the harmony of Heaven and Earth, nothing is greater than music; to exhaust the essence of music, nothing is greater than the qin. Among the eight sounds, silk is the sovereign; among silk instruments, the qin is the sovereign; and within the qin, the middle position (zhonghui) is the sovereign.

Thus, the gentleman always keeps it at hand, never leaving it — unlike bells and drums, which are arranged in the hall below and set upon hanging racks. Because it is moderate in size, its sound is harmonious:

Loud tones do not become clamorous and scattered, yet they flow widely.

Soft tones do not become muffled and extinguished, yet they remain audible.

Thus, it is sufficient to move a person’s virtuous heart and restrain their wicked intentions, ultimately leading them into the realm of balanced harmony.

Creating the five-stringed qin, and singing the Southern Wind (Nan Feng) lyrics, to harmonize the five tones — this began with Shun. Southern Winds have the energy of growth and nourishment; the qin is the sound of the summer solstice.

Shun, using his virtue of nurturing life, spread the sound of the summer solstice — this was the beginning. His affection and joy in parental bonds transformed the world — this was the end. His affection and joy in parental bonds made it so that all under Heaven recognized the father-son relationship.

Thus, if one says that "the qin's sound is harmonized and the world is governed," nothing achieves this more than the five tones — is this not precisely the case?

Yangzi (Yang Xiong) said: "Shun played the five-stringed qin, and the world was transformed." The tradition says: "Shun played the five-stringed qin, sang the Southern Wind poem, and without stepping outside his hall, the world was governed."

From this, we see that Shun playing the five-stringed qin and singing of the Southern Wind was nothing more than praising the virtue of parental care and expressing the heart of filial piety, using it to resolve his sorrows. Was this not merely to ease the people’s grievances and enrich their lives?

Appendix II

The text here is copied from Folio 120 of Chen Yang's Yue Shu. Four segments are mentioned here:

古者,瑟為正樂,琴為清樂。

正樂以治人,清樂以修身。

故君子尚瑟,小人好琴。

然則瑟之為樂,非徒聲音之美也。

In antiquity, the se was for formal music; the qin was for pure music.

Formal music governs the people; pure music cultivates the self.

Therefore, goverment officials esteem the se; common people favor the qin.

Thus the se as music, is not merely about the beauty of sound.

Literal English Translation: Qin Practices

From the Three Dynasties onward, the kings all cultivated their own persons in order to bring peace to the people, regulated their households in order to govern the realm. They necessarily had a Way by which to realize their sincerity, and they necessarily had an instrument by which to carry the Way. Thus, the sages created the qin as a form of music.

The word "qin" itself means to be under control: controlled from deviation and returning to correctness, harmonizing human relations, and stabilizing customs. Its sound is pure; its virtue is tranquil; its aspiration is distant; its interest is deep. In lesser matters, it may ease emotions, cultivate the self, and nourish one’s nature. In greater matters, it may regulate the household, order the state, and teach others.

Thus, the Son of Heaven must possess one; the feudal lords must practice it; and the households of the gentry and commoners alike must not be without it.

As for the power of music to move people — it uses sound to communicate feeling. Where feeling is deep and meaning far-reaching, the sound is mournful. Where feeling is balanced and intent upright, the sound is clear. Where feeling is intense and aspiration lofty, the sound is strong. Where feeling is warm and conduct sincere, the sound is harmonious.

When the sound is harmonious and the rhythm well-measured, it enters the ear and lodges in the heart, stirs from within and takes form without. It may move Heaven and Earth; stir ghosts and spirits; rectify ruler and minister; harmonize upper and lower; regulate husband and wife; and complete moral transformation. Therefore, the sages of antiquity never spent a day without the qin.

Thus the Book of Songs says: “Strike the qin and se, to express my resentment; speak appropriately, drink wine, and grow old together with you.” The Tradition says: “Master Zisang recited poetry and read books, struck the qin and se for his own delight.” The Rites say: “A scholar does not discard his qin and se without cause.”

As for using the qin as discipline — it is because it may govern the mind, nourish one’s nature, ward off deviance, correct behavior, restrain stray or perverse thoughts, steady the heart in times of danger, assist teachings not yet realized, and express the most subtle principles. Truly, the sages’ use of the mind was profound indeed.

In ancient times, when Fuxi ruled the world, he looked upward and observed patterns in the heavens, looked downward and observed models on earth, looked inward and observed laws among men. From these he created music, to express the virtue of spirit beings, to correspond to the emotions of all creatures.

He then carved tong wood to make a qin, and twisted silk into strings to represent the harmony of Heaven and Earth, to communicate the virtue of the spirit world, and to match the emotions of all things.

Its sounds — gong, shang, jue, zhi, yu — encompass the five tones. They respond to pitch standards and harmonize with bells; they combine into pitches that form full melodies. Therefore, the qin can move Heaven and Earth, stir spirits and deities, harmonize human relations, and fulfill moral teaching.

It causes traitorous ministers and rebellious sons who hear it to have their hearts broken; it causes filial sons and obedient grandsons who hear it to have their virtue arise.

Therefore, what the sages value in the qin is its ability to move Heaven and Earth, stir spirits and deities, rectify ruler and minister, harmonize high and low, unite husband and wife, and bring about moral transformation. That is why sages practiced it daily and never set it aside.

The Erya says: “Pacing" when playing a qin melody (with the right hand), is playing this without pressing down on the strings (with the left hand). The resulting sound lacks ornamentation and thus it should not be called "music".

However, the ancients regarded this as the beginning of patterned sound, and so they called it "pacing" (which implies marching to a beat).

Indeed, this "pacing" is the beginning of movement, and so it is an incipient form of music. Thus learners practice this (i.e., play with open strings) in order to understand the basics of rhythm.

Return to Qinshu Daquan Folio 2 entries 7 and 8, the above commentary on Yue Shu or the

top.

琴瑟論:琴瑟上、琴瑟中、琴瑟下

Discussion of Qin and Se (Qin Se Lun), in three parts

In ancient times, the use of the qin and se was suited to their respective sound types. Yunhe (Cloud Harmony) is from a yang place, and its qin and se are suitable for performance at the Circular Mound Altar. Kongsang (Hollow Mulberry) is a yin place, and its qin and se are suitable for performance at the Square Marsh Altar. Longmen (Dragon Gate) was carved out by human effort, and its qin and se are suitable for performance in the Ancestral Temple. Emperor Zhuanxu was born in Kongsang, Yi Yin was born in Kongsang, and Yu the Great carved out Longmen — all of these names are derived from their respective places. Thus, could Yunhe be what the Yu Gong (Tribute of Yu) refers to as Yuntu (Cloud Soil)?

Blind musicians were in charge of playing the qin and se. In the Book of Songs, "The Deer Call" (Lu Ming) states: "Drum the se, drum the qin." The Book of Documents says: "With the qin and se, chant praises." The Great Commentary (Da Zhuan) also says: "The great qin has polished strings, reaching across; the great se has vermilion strings, also reaching across." The Erya states: "A great qin is called a 'li'; a great se is called a 'sa'."

From this, we can see that the qin is easy and fine, while the se is calm and good. They are both primarily used in the Shanggong (upper palace music), and they have never been used without complementing each other. The Mingtang Wei states: "The great qin, the great se, the middle qin, and the small se were the musical instruments of the Four Dynasties." The ancients made music in such a way that the sounds responded to each other to form harmony, and the large and small did not exceed their proper measures, achieving balance. Thus, when using a great qin, it must be paired with a great se; when using a middle qin, it must be paired with a small se.

Only then does the large not overpower, the small not become suppressed, and the five tones achieve harmony. The Rural Drinking Ceremony (Xiang Yin Jiu Li) states: "The musicians are all present; to the left is He playing the se, and behind is Shou playing the yue." The Banquet Ceremony (Yan Li) states: "A minor official sits to the left playing the se, facing forward while holding a yue." The Record of Music (Yue Ji) states: "The se of the Pure Temple had vermilion strings, widely spaced apart." The Book of Songs says: "Sitting together, playing the se — why not play the se every day?" The Commentary mentions: "King Zhao of Zhao played the se for Qin." These passages do not mention the qin but rather use the se to represent the qin.

When Shun created the five-stringed qin, he sang Southern Winds (Nan Feng) poem, yet the se was not mentioned — this was to use the qin to represent the se. Later generations had the "elegant qin" (ya qin), elegant se (ya se), hymn qin (songqin), and hymn se (song se) — could this be because their sounds were suited to the Ya and Song sections of the Book of Songs?

The qin is one (unified). Some say it was created by Fuxi, others say by Shennong, and others claim Di Jun ordered Yanlong to make it. The se is also one. Some say Zhu Xiangshi ordered Shi Da to make it, others say Fuxi made it, and yet others claim Shennong and Yanlong made it. Could all these accounts have simply been passed down from hearsay?

Some (vague) old accounts suggest that perhaps it was Zhu Xiang who ordered Shi Da to create a five-stringed se, which was then played by Gu Sou (Shun’s blind father).

It is also said that this was later increased to fifteen strings, and that Shun further added to it, making it twenty-three strings. Still others say the Great Emperor (probably the Yellow Emperor) had Su Nü play a fifty-stringed se, but the emperor for some reason was then so overcome with sorrow and that he could not bear it, so he broke it, reducing it to twenty-five strings. Guo Pu claimed, "The great se is called a 灑 sǎ". It is also said there is a twenty-seven-stringed version.

That which is above form is called the Dao; that which is below form is called the instrument.” The qin is the music that gentlemen and scholars constantly keep by their side. When unhewn and scattered it forms an instrument; when its principles are understood it manifests the Dao. Only the gentleman truly delights in obtaining this Dao, and thus uses his heart to commune with it. He plans to do so all his life, and even without any particular reason he will not set it aside even for a moment. Therefore he is able to go beyond the mere physical instrument of raw wood and enter into the enlightened principle of the Dao, ultimately carrying the Dao with him and uniting with it.

Now, the music of the qin is meant for chanting and singing, and so it has distinct categories such as chàng (暢, ode), cāo (操, lament or song), yǐn (引, prelude), yín (吟, chant), nòng (弄, medley), and diào (調, tune). For example, Yao’s piece “Shen Ren” (“Divine Person”) is a chang composed as harmonious music; Shun’s “Si Qin Cao” (“Thinking of Parents”) is a cao composed to express filial longing. Pieces like “Xiangyang” and “Kuaiji” belong to the cao of the Xia dynasty; pieces like “Xun Tian” belong to the cao of the Shang; pieces like “Li You” belong to the cao of the Zhou. Those called “yin” (引) include, for example, the state of Lu’s “Guanju Yin” and the state of Wei’s “Si Gui Yin”; those called “yin” (吟) include “Jizi Yin” and “Yiqi Yin”; those called “nong” include “Guangling Nong”; those called “diao” include “Zijin Diao”. Likewise, the (qin names) “Qingjiao” of the Yellow Emperor, “Haozhong” of Duke Huan of Qi, “Raoliang” of King Zhuang of Chu, “Lüqi” of Sima Xiangru, and “Jiaowei” of Cai Yong, up to names like "Jade Bed", "Echoing Spring", "Resonant Chime", "Pure Clarity", "Delighting the Spirit", and so on – qin are simply different names for qins. And techniques such as yín (吟, fast vibrato), náo (猱, slow vibrato), sàn (散, playing open strings), yì (抑, pressing), mǒ (抹, inward rubbing), tī (剔, outward plucking), cāo (操, strumming), fǔ (撫, brushing), bò (擘, plucking with thumb), lún (綸, outward plucking of a string with several fingers), cù (促, quick notes?), chuò (綽, slowing up to), cuō (縧, accelerating?) and the like are all methods of sound production on the instrument. When labeled a "chàng", a piece is gentle and harmonious; when labeled a "cāo"", it is solemn and formal. A "yǐn” (prelude) leads into and explains a melody; a “yín” (chant) recites and intones its theme; a "nòng" is to play and practice it; a “diao” is to adjust and harmonize it. In all, there are thirteen methods of sound (or types of compositions) – as explained in detail by earlier scholars.

瑟,琴操,步

Discussion of Se, Qin and Bu; three of the last four parts of this section)

自三代之王者,皆修其身以安百姓,齊其家以治天下,必有道以致其誠,必有器以載其道。

是以聖人製琴以為樂也。

琴者禁也,禁邪歸正,以和人倫,以平風俗。其聲清,其德靜,其志遠,其趣深。小可以閑情,修身以養其性;大可以齊家,理國以教於人。

故天子必備焉,諸侯必習焉,士庶之家亦不可闕焉。凡音所以動人者,因聲以通其情也。情深而意遠者,其聲悲;情和而義正者,其聲清;情烈而志高者,其聲壯;情溫而行篤者,其聲和。聲和而節中者,入於耳而藏於心,動於中而形於外,可以感天地,可以動鬼神,可以正君臣,可以和上下,可以齊夫婦,可以成教化。是以古之聖人,無日不琴焉。

故《詩》曰:鼓琴鼓瑟,以寫我憤,宜言飲酒,與子偕老。《傳》曰:子桑戶誦詩讀書,鼓琴瑟以自娛。《禮》曰:士無故不徹琴瑟。夫以琴為操者,以其可以治心,可以養性,可以避邪,可以正行,可以閑邪僻之念,可以定傾危之心,可以濟未至之教,可以宣幽微之理也。蓋聖人之用心深矣!昔伏羲氏之王天下也,仰則觀象於天,俯則觀法於地,中則觀法於人,因而制樂,以通神明之德,以類萬物之情。乃斲桐為琴,綰絲為絃,以象天地之和,以通神明之德,以類萬物之情。其聲宮商角徵羽,五音備焉。應律協鐘,合宮成聲,故能動天地,感鬼神,和人倫,成教化。使亂臣賊子聞之心破,孝子順孫聞之德生。是故聖人之所貴於琴者,以其可以動天地、感鬼神、正君臣、齊上下、合夫婦、成教化也。聖人所以日習之而不廢也。

爾雅曰:徒鼓琴謂之步,蓋不按弦而鼓之也。

其聲無文,故不成樂。

然古人以為節奏之始,故名之曰步。

蓋步者,行之始也,樂之序也。

故學者習之,以知節奏之本。

Return to the top,

or to the Guqin ToC.