|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| XLTQT ToC / Guanshan Yue from Meian Qinpu | 聽錄音 Listen to my recording with transcription / 首頁 |

|

120. Recalling Guanshan

- Wuyi tuning2: 1 3 5 6 1 2 3 See also #121 Han Gong Qiu |

憶關山

1

Yi Guanshan |

The reference to Guanshan is unclear. There are various places called Guanshan, in particular in Shandong and several parts of Shaanxi, but the words are also used to mean mountain passes in general, and often are used mainly as an allusion to being far from home. The present melody's function as a prelude to Han Gong Qiu suggests the latter meaning is intended here.

Yi Guanshan has no relationship to the popular modern melody of the Mei'an School, Guanshan Yue (Moon over Guanshan).5

Original Preface

None

Music 6

Three sections, untitled

(see transcription;

timings follow my recording 聽錄音; followed by Han Gong Qiu)

00.00 1.

00.45 2. (harmonics)

01.28 3.

02.10 harmonic coda

02.25 end

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Recalling Guanshan (Yi Guanshan 憶關山)

11558.xxx, but this title can be found in a Song dynasty melody list, grouped with other melodies having the same huangzhong tuning as here. Old melody lists also include the title Traversing Guanshan (度關山 Du Guanshan); 9512.81 says this is the name of a

Yuefu Shiji Matching Song (YFSJ 相和曲名 Xianghe Qu; Folio 27, p.391).

As for Guanshan itself, 42402.10 關山 has three entries:

- 關與山 "passes and mountains". For this it quotes several poems including 木蘭辭 Mulan Ci (anonymous Mulan Lyrics), and 滕王閣序 Preface to 'Pavilion of Prince Teng' by 王勃 Wang Bo (649-676; translated in Columbia Anthology, p.552, and also a qin song in 1585).

- 鄉里 "native place". For this it quotes 關山月詩 the poem Moon over the Mountain Pass by 徐陵 Xu Ling (507-583); it is not in his New Songs from a Jade Terrace.

- 鎮名 "name of a district", mentioning one in 山東省東阿險 Shandong and another in 陝西省臨潼縣東北 northeast Lintong County of Shaanxi province (east of Xi'an)

Modern maps actually show quite a variety of places called Guanshan, including several in Shaanxi province and a gate in the Great Wall west of Dunhuang in Gansu province. There is also a popular mountain in Taiwan of that name.

See further below under Guanshan Yue.

(Return)

2.

Wuyi mode (無射調 Wuyi diao)

See also Shenpin Wuyi Yi. From standard tuning lower the first and raise the fifth strings a half step each.

(Return)

4.

Tracing Yi Guanshan

For this melody, surviving only in 1525, see Zha Guide 21/--/--.

(Return)

5.

Music of Yi Guanshan

To my knowledge the rhythmic patterns of this melody do not fit any lyrics.

(Return)

6.

Relation to modern Guan Shan Yue

Appendix

Claims of a connection have not been substantiated.

(Return)

關山月 Guan Shan Yue

Moon over Guan Shan

| Guanshan Yue in Longyinguan Qinpu |

This introduction to this popular modern melody was originally included here as an appendix to Yi Guanshan in part because the similarity of names in their titles has sometimes led to people thinking there is a melodic relationship (there is none), but also because it is a modern melody that I had not learned from my teacher, Sun Yuqin.

This introduction to this popular modern melody was originally included here as an appendix to Yi Guanshan in part because the similarity of names in their titles has sometimes led to people thinking there is a melodic relationship (there is none), but also because it is a modern melody that I had not learned from my teacher, Sun Yuqin.

(There are a number of recordings available; for silk string recordings see in particular this recording by Zha Fuxi [melody played three times] and this video by Peiyou Chang [played twice]).

The "Guanshan" of the title could be the name of a specific frontier region mountain pass (as well as one on the island of Taiwan). However, as mentioned above, this title could also be translated simply as Moon over a Mountain Pass. And although old poems of this title usually concern soldiers on the frontier separated from their loved ones at home, that does not seem to have been the intention here.

As a qin melody title Guanshan Yue seems to survive as a printed melody only from the Meian Qinpu (1931; see QQJC XXIX/203), a handbook consisting of melodies taught by Wang Binlu (1867 - 1921). There are, in fact, at least two possible hand-copied predecessors, but the authenticity of their dates is somewhat in doubt:

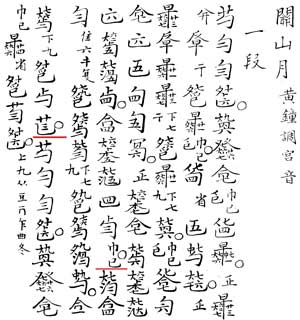

- The tablature at right from Longyinguan Qinpu, said to date from 1799, but its date is not confirmed; until recently it was known only as a hand copied collection of melodies belonging to Wang Binlu himself. All the Longyinguan Qinpu melodies are also in Meian Qinpu, and all are virtually identical; the main differences between the Longyinguan Qinpu and Meian Qinpu versions of Guanshan Yue are that the latter divides the melody into two parts plus a coda (at the places indicated here by the addition of red lines), and the former includes instructions at the end only to repeat the melody once, not continuously, as discussed further below.

- Tablature in Qinxue Guanjian (QQJC XXIX/277); Zha Fuxi seems to give its date as 1930, but elsewhere it is said to date from 1870. It has a few differences from the Meian version.

In any case, after its publication in Meian Qinpu Guanshan Yue quickly became a very popular beginners' melody using standard tuning. Its own preface (1959 edition) is as follows (translation is from Fred Lieberman, A Chinese Zither Tutor, p. 86 [Romanization changed]):

Regarding the "fashion called 'jade bracelet'" (玉環體 yu huan ti), this term is also used at the end of the tablature (which ends with the right hand second finger plucking the sixth string outward while the left ring finger slides up into the 10th position), where it says then to "slide up to the 9th position then do again the jade bracelet structure": i.e., repeat it as many times as you like. The Longyinguan Qinpu version does not mention repetition, but this sort of repetition can in fact also be applied to some other beginners's melodies, such as Xianweng Cao.

Versions with lyrics added

None of the surviving editions adds lyrics, or mentions any connection between the melody Guanshan Yue either to earlier poems of this title or to other possible related melodies. Nevertheless, claims have been made both that Guan Shan Yue is a song going back to the Tang dynasty, or that it is based on an old Shandong folk melody. The most common assertion connects Guanshan Yue with a Tang poem by Li Bai.

42402.11 關山月 identifies Guanshan Yue as 漢橫吹曲名 the name of a Han dynasty Hengchui Qu (Song Accompanied by Horizontal Flute). It then mentions

Yuefu Shiji, which has 23 poems of this title in its Folio 23. The first 13 have the structure [5+5] x 4, as do 4 later ones. Only the 13th, by Li Bai (YFSJ, p.337), and the 23rd have the structure [5+5] x 6. The one by Li Bai is the most famous.

Li Bai's poem Guanshan Yue is as follows (translation is from Fred Lieberman, A Chinese Zither Tutor, p. 88 [Romanization changed]):

長風幾萬里, great wind from faroff lands

漢下白登道, Han march down Bai Deng

由來徵戰地, returning from places of battle

戍客望邊色, frontier guardians watch borders sadly

高樓當此夜, in boudoirs on this night

However, although the structure of the modern Guanshan Yue melody does allow the Li Bai poem to be paired to it quite successfully, the pairing does not follow the pairing method used for almost all melodies in any earlier handbook, plus there is no evidence suggesting any attempt was ever made to pair the melody with the Li Bai lyrics until at least the late 20th century. Nevertheless, the common assumption today that this pairing is quite ancient - even that the melody is ancient - has no basis in the actual evidence.

The main problems with the assumption that the music was created to go with the lyrics (or the lyrics to go with the music) are:

These facts have not prevented people from claiming it as "Chinese Ancient Music" when they dress up in ancient costume and sing the Li Bai poem using the Meian Qinpu melody. Because the latter is actually a modern composition or a modern arrangement of a folk melody of indefinite age (see below), and for such performances it is always played on a modernized (i.e., nylon metal string) qin, sometimes with the addition of an ensemble of modernized versions of traditional instruments, such performances may be lovely but they are the antithesis of HIP.

For a more natural, and timeless, feeling listen to recordings such as those linked above

蒼茫雲海間。 vast expanse ocean of clouds

吹度玉門關。 blows through Yumen Pass

胡窺青海灣。 Hu reconnoitre Qinghai Bay

不見有人還。 no one yet has been seen

思歸多苦顏。 homeward thoughts many bitter faces

嘆息未應閒。 only sighing and no rest

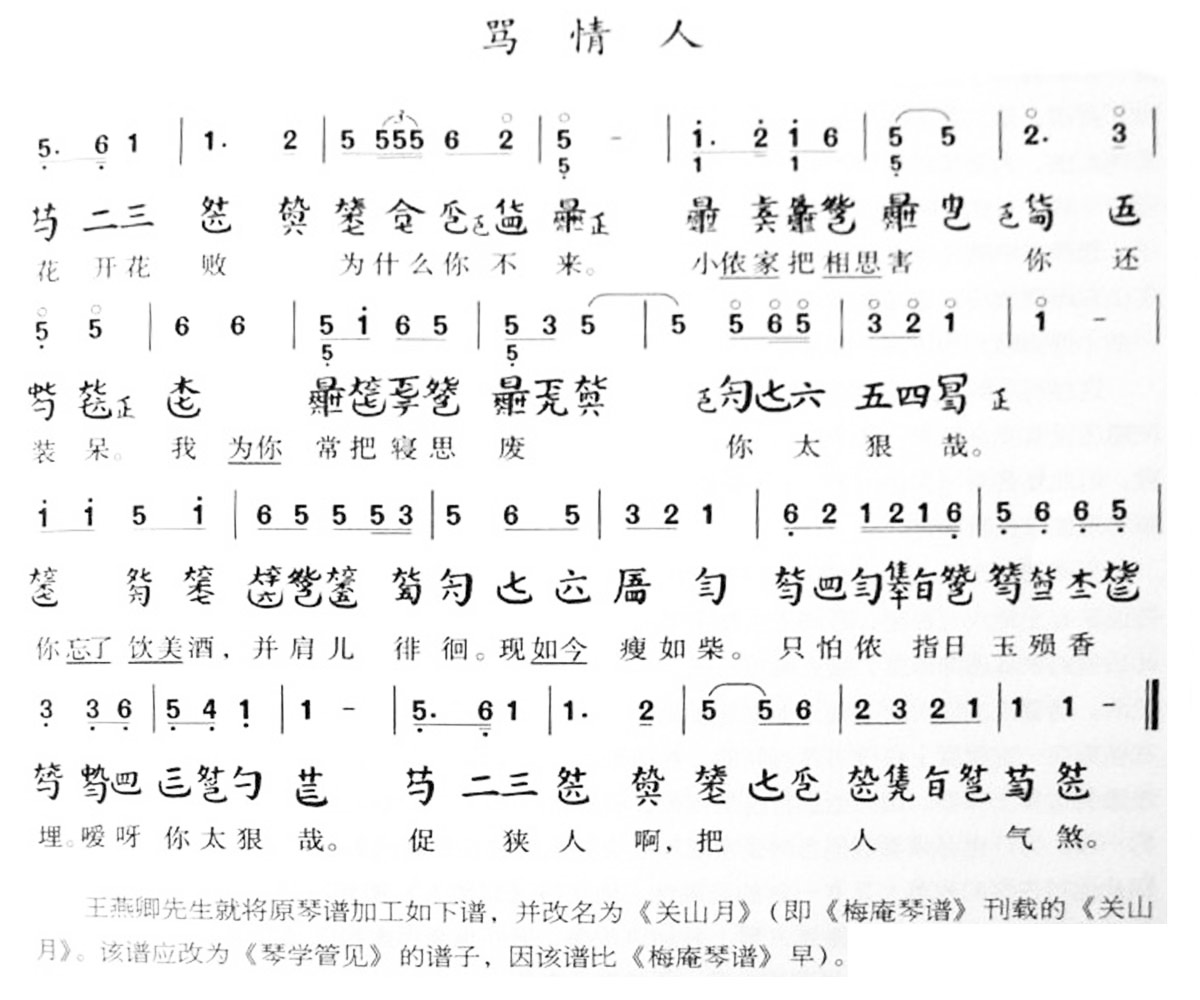

| 關山月 Guanshan Yue: folk origin in 罵情人 Ma Qingren (Scolding My Lover)? | Transcription of 罵情人 Ma Qingren (expand) |

For adding lyrics to Guanshan Yue? Guan Shan Yue a much better case has been made that its source is actually a Shandong folk song called "Scolding my lover" (Ma Chingren). If this is true, it has important repercussions on related issues involving Meian Qinpu.

For adding lyrics to Guanshan Yue? Guan Shan Yue a much better case has been made that its source is actually a Shandong folk song called "Scolding my lover" (Ma Chingren). If this is true, it has important repercussions on related issues involving Meian Qinpu.

The case for the melody's source in Ma Chingren apparently comes from the following article,

Zhang Yujin, A Thorough Investigation of Guanshan Yue. Qinlun Chuoxin

(Reprinted [?] in 林晨,琴學六十年論文集,文化藝術出版社; 第1版,2011年5月1日 ?)

Zhang Yujin (1914~1981; specialist on Zhucheng school) argued that the source of the famous guqin melody Guanshan Yue is a Shandong folk melody called Ma Qingren (28958.xxx; it does not appear either in any traditional qin handbooks or in any known traditional collections of folk melodies). He wrote that, prior to the publication of the Mei'an Qinpu in 1931, when Wang Binlu was playing and teaching the melody in Nanjing, the story immediately became very popular that its origin was a Han dynasty 橫吹曲 military music piece retexted by Li Bai; Yuefu Shiji has these lyrics in its Hengchui section (reference linked above). This is the background for the story told just above and apparently still popular.

However, Zhang's reseach showed that the melody's true origin was in a folk melody called Ma Qingren, once quite popular in the 泰安 Tai An region of Shandong. If this is true, and apparently Zhang made a very strong argument, it then argues against or precludes any argument that the folk melody Ma Qingren was in fact insprired by Guan Shan Yue rather than the other way round. Here it is not always clear when writers are referring to a melody or the lyrics or both, but if what Zhang wrote is correct, it does not seem possible that either Longyinguan Qinpu or Qinxue Guanjian could date from the times commonly assigned to them.

Other more recent online articles have included transcriptions of the melody and lyrics for Ma Qingren. For example, 中國古琴音樂文集 Zhongguo Guqin Yinyue Wenji included a transcription of a melody said to be called Ma Qingren together with its lyrics, but I have not yet been able to read the text of that article. Subsequent to that I found transciptions online that include the lyrics, such as those here at right (enlarge). Here are the lyrics as included there:

花開花敗,為甚麼你不來?

小儂家把相思害,你還裝呆。

我為你長把寢思廢,你太狠哉。

你忘了飲美酒,並肩兒徘徊。

現如今瘦如柴,只怕儂指日玉隕香埋。

哎呀,你太狠哉,

促狹人啊,把人氣煞。

Scolding my beloved

Flowers bloom, flowers fade — why is it you don't come?

Little me, by longing harmed — and still you act dumb.

For you, long have I ruined sleep and thought — you are too cruel!

You’ve forgotten drinking fine wine -- and walking side by side.

Now I’m thin like firewood — afraid that soon I’ll fall, jade lost and fragrance buried.

Aiya! You’re too cruel!

Your teasing heart — it makes me so mad I could die!

The number notation with the above lyrics shows a melody very similar to that of Guanshan Yue. The comment below the transcription (王燕卿先生就將原琴譜加工如下譜,並改名為《關山月》(即《梅庵琴譜》刊載的《關山月》。 該譜應改為《琴學管見》的譜子,因該此《梅庵琴譜》早)。) points out the similarity of the melody, adding that most people think Meian Qinpu was the earliest to have it, but it then says Guanshan Yue really should be dated to Qinxue Guanjian, putting its date at 1870.

Interestingly, not only does that comment make no mention of the lyrics, it also makes no mention of the even earlier claims made for dating the same melody to Longyin Guan Qinpu (see #3). As just mentioned, both of these earlier dates are contradicted by what Zhang Yujin wrote about Wang Yanqing (Wang Binlu, 1867-1921) having arranged Guan Shan Yue from a current Shandong folk melody.

Here one might ask why commentary in Meian Qinpu only says of this melody things like "according to tradition", with no mention of Ma Qingren or its lyrics.

If transcriptions such as the one above of Ma Qingren are in fact directly based on a Shandong folk song of that title, then one would have had to have been copied from the other. However, the internet sites that have images of it add minimal comment, little more than "It has been said that...," and so it is difficcult to have a properly informed discussion this issue.

As a result I can add only the following speculation.

On the one hand, if one applies the traditional pairing method for qin songs to the Guanshan Yue tablature, the "dian" (points where lyrics can be placed) fit the Ma Qingren lyrics much better than they do the words of the Li Bai poem. On the other hand, the fact that the Ma Qingren lyrics do fit so closely makes it especially odd that the connection was not made earlier. The traditional pairing rules of qin melodies are so explicit that unless its "dian" are quite regular it is already sufficiently difficult to find matches between existing melodies and existing lyrics, so that if someone does find such a match it is very strong evidence for such a connection - or that one or the other was manipulated to try to establish or make clear the connection. (This is presumably what has happened to the opening phrase of Guanshan Yue, where in the version of the official Chinese conservatory syllabus an additional stroke has been added [repetition of the open third string]; on the other hand, no similar attempt is made later in the melody to pair the lyrics and music in the traditional manner.)

In addition, if in fact lyrics for Ma Qingren can not be found in an older source, it would be good to see further analysis as to whether they fit into the style of folk songs published as early as the 1799 often claimed for Longyinguan Qinpu. This is an important issue, as it could have bearing on the question of whether Longyinguan Qinpu actually dates from much earlier than the 20th century.

To repeat, if Ma Qingren really is the source for Guanshan Yue that seems to preclude the dates given for both the Longyinguan Qinpu and Qinxue Guanjian: their modern form must date no earlier that when Wang Binlu himself actually played it.

As a final note, it would be interesting to find old or new discussions about the advantages and limitations of the the traditional method of pairing words and music following the traditional method, especially comments that suggest the method was not being used or should not be used. However, none of this is an argument agains actually doing such non-traditional pairing today: a beautiful result is a sufficient argument for doing that. However, claims should not then be made that this is evidence that it was done in past, though it can be pointed out that oral traditions are not always accurately described in written accounts.

Return to the top