|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| XLTQT Original ToC Comments Tunings Zha preface Tang Gao preface Pursuing antiquity Further | 首頁 |

| Wang Zhi: Introductory Discourse 1 | 汪芝:叙論 |

| From Xilutang Qintong | 西麓堂琴統, 1525 (not 1549) |

| Original text (Expand) |

Note:

What is here the fourth paragraph (中文; indented) is written entirely in four character phrases except for three additions: "予嘗" at the opening, "乃" a few phrases later, then "耳爾" at the end. However, there is no rhyme scheme here that would make this into a poem. On the other hand, it might be appropriate as theme song lyrics for anyone who has spent a lifetime trying to reconstruct an early music tradition.

In remote antiquity, when music was first created, the qin truly led the way. Among the eight tones (i.e., the bayin classification), it held its place alongside all others, serving as both guide and companion in the harmony of ruler and minister. Was it not from this source that the entire system arose?

It (i.e., the qin) was played regardless of rank — among the poor and the noble, the great and the small alike. It became woven into daily life, yet its origins stretch back beyond reckoning. Since the fall of the Western Capital (Chang'an), its tradition has gradually fallen into obscurity. Few now understand it; and those with true dedication to its study appear only rarely, once in an age. And even when such individuals do emerge, they often begin obscure and end distinguished — their official duties eclipse their artistic pursuits. If their lives are cut short, their fame dies with them. Thus, nothing of them is passed down to later generations.

Occasionally, something is transmitted, but it's often riddled with contradictions and distortions — pieces are buried in muddled notation. Phrases obscure their own melodies; forms and sounds are rendered crude and indistinct. One finds no way to trace the threads — it is like standing before a wall or gazing at the ocean in vain. Today’s students suffer even more from this confusion!

hunting through a great number of sources, amassing a collection of documents - they have piled up to the ceiling.

I then analyzed their terminology and clarified meanings, winnowed chaff from grain,

and compiled them into this present volume, hoping thereby to recover the original versions.

As for the notes and modality ("five notes, six modes"), I compared and connected,

put them into categories, thereby not omitting anything great or small.

As for every phrase of the melodies in the tablature, nothing remains obscure;

I have worked on this from my early twenties, until now in my gray-haired years.

I have worked on this for nearly thirty years: it has taken all this time just to bring the work into proper form.

Thus have I strained myself to complete this book, but it has merely been a private joy, and that's all.

Alas! With frivolous elegance all around, and the truly great music very scarce, this treasure is viewed as no more than an old worn-out broom. Who can understand the depth of my unceasing labor? Yet I have heard it said: one who clutches raw jade (knows inner worth) will not move to Chu; one who plays the se will not be infatuated with (worldly states such as) Qi. Noble people hold fast to their purpose — and this is the way it is. This work may be neglected or may be embraced, but this not for me to decide.

As for myself, coarse and limited as I am, shallow in understanding and narrow in learning, I have not mastered the art of creativity. With an embarrassed face I wield my lance (unqualified as I am), aware that a true master of sound like Yongmen (Zhou) had sound that was both powerful and moving. Compared to the great worthies of old — true luminaries of a hundred generations — how dare I flatter myself?

And yet, the Way of the qin is vast indeed! It is what expresses the harmony of the five notes, cultivates uprightness of feeling, and communicates with the virtue of spirit and the divine. Unless one’s heart dwells in spacious stillness, cleaving to authenticity and transcending mere ink and sound, attaining natural ease amidst forests, wind, water, and moonlight—who could truly be part of this Way?

As the Book of Documents says: “All things are born with feeling; feeling carved out becomes sound.” The five notes arise from the five elements, then proceed by intervals of a fifth: gong gives rise to zhi, zhi to shang, shang to yu, and yu to jue.

Thus:

Strike zhi and shang responds;

Strike shang and yu responds;

Strike yu and jue responds.

And thus:

Simple, open, square, and sparse—this is shang;

Subtle, pure, long, and profound—this is jue;

Bright, eloquent, grand, and tight—this is zhi;

Delicate, cohesive, refined, and light—this is yu.

These are the proper natures of the five tones.

Shang is square and shaped into instruments, like a goat wandering from the herd—it governs structure.

Jue is upright and lofty, like a rooster ascending a tree — it governs rising energy.

Zhi is bright and discerning, like a startled boar — it governs distinction.

Yu is moist and nourishing, like a neighing wild horse — it governs exhalation.

Those are distant analogies drawn from natural phenomena, to pursue and exhaust the underlying principles.”

From the lungs, with open mouth and exhalation, comes shang;

From the liver, with bared teeth and rising lips, comes jue;

From the heart, with teeth closed and lips parted, comes zhi;

From the kidneys, with parted teeth and pursed lips, comes yu.

And those are analogies drawn from the body itself, in order to fulfill the understanding of human nature

However, today’s learners seek only what pleases the ear. In doing so they change and embellish, wandering further astry, and bringing confusion to the art. Indeed often they even cannot distinguish gong, shang, jue, zhi, and yu. This is as though one were painting without knowing the five colors. How, then, can one hope to capture subtlety?

(Thus has) the ancient spirit grown faint. And in the thousand years since, has made little true progress. Among the low and vulgar, what hope can we place?

Thus, the voice cannot help but find its home in the qin.

夫邃古作樂,琴寔先之。八音並行,君臣相御。胥此焉?

統貧賤大小,由諸日用,其來邈己,西都以降,其道䆮夷,知者或寡,有志之士亦閒世而出,然其人始微終顕,則業掩其藝,肥遂不復,則名隨身殄,是以後世無傳焉。

或有傳者,亦舛錯謬戾,曲以譜湮。句自曲晦,形聲之粗,莫可尋繹,使若面牆而立,望洋而嘆,今之學者益病矣!

予嘗抗志遺譜,博採諸家,搜獵頗多,積之充棟。

嗟夫!

靡曼在側,太音正希,千金敝帚,孰知予之苦心哉?然予聞抱璞之士不為楚遷,操瑟之人不為齊病,君子尚志,亦若是而已。其於暌合行尼,非所敢必也。顧予凡陋,寡昧研窮,未精作者之場,靦面橫槊,若夫振響雍門抗聲,前哲則有百世之髦士,在予何佞諸。

琴之為道大矣!所以宣五音之和,養性情之正,而通神明之德也。茍非宅心衝曠,契真削墨,超然自得於林風水月之間者,其孰能與此哉?

書云:

「物生而有情,情鑿而為聲。」五聲本於五行,布於五位:宮生徵,徵生商,商生羽,羽生角。

故:

五聲之正也:

蓋遠取諸物,以窮理者焉。

出於脾合口而通之為宮,

蓋近取諸身以盡性者焉。

後生學者唯悅耳是趨,彼此遷飾滋遁以紊,且宮、商、角、徵、羽之不分。猶不知五色而繪也?

矧足語其幾,古風寥寥。千載而下,其無駸駸。於下俚者,詎可望耶?

此聲之所以不能不朞於琴矣。

1.

Introductory Discourse

This preface has also been translated by Peiyou Chang -- see

her website.

Return to the annotated handbook list

or to the Guqin ToC.

乃析名辨義,揚糠披沙,匯為茲編,冀於反本。

五音六律,比類而附,支分目舉,巨細靡遺。

譜曲句字,莫有隱晦,肇自弱冠,迄於二毛。

垂三十年,甫克就緒,黽勉成帙,聊以自娛耳爾。

彈宮而徵應,

彈徵而商應,

彈商而羽應,

彈羽而角應。

故:

宏盛而玄圓而重者,謂之宮;

簡易而通方而踈者,謂之商;

幽約而潔長而邃者,謂之角;

開爽而文洪而密者,謂之徵;

縝凝而備細而輕者,謂之羽。

宮性圓而居中,若牛之鳴窌而主合;

商性方而成器,若羊之離群而主張;

角性直而崇高,若雞之登木而主湧;

徵性明而辨物,若豕之駭__而主分;

羽性潤而澤物,若野馬之鳴而主吐。

出於肺開口而吐之為商,

出於肝而張齒湧吻為角,

出於心而齒合吻開為徵,

出於腎而齒開吻聚者為羽。

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

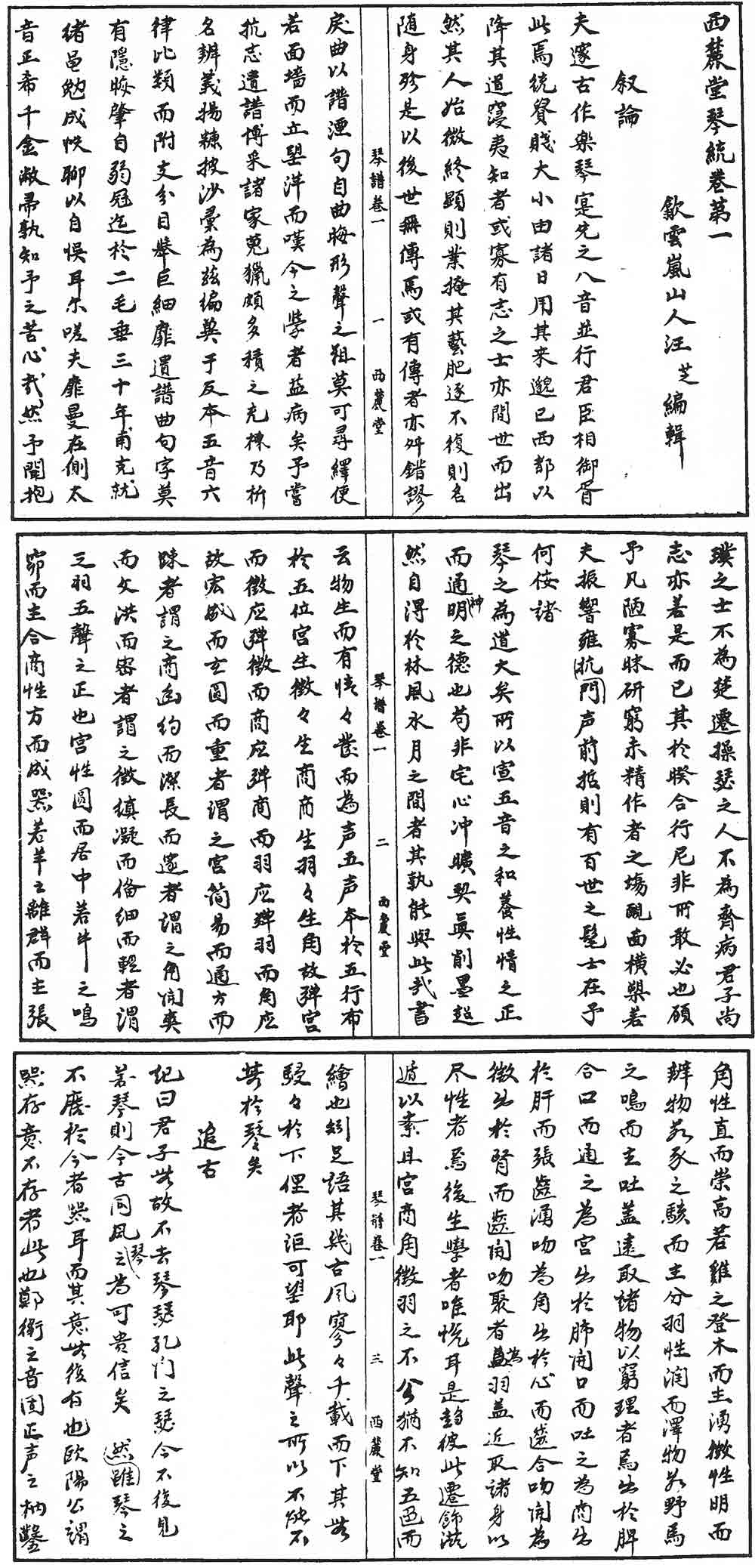

The original text of this preface (see image at top) was copied and reformatted here from ctext, which said it used OCR. OCR yields many errors with texts like this. In fact the sections just before and after this section are riddled with errors. However, this part was punctuated and someone clearly had made corrections.

(Return)